With the president and Congress out of town, Washington, D.C. is very quiet during the holidays, without the long lines one normally sees at museums and capitol attractions. So it was a good time last week to take my family to see a wonderful exhibit at the Library of Congress, jointly sponsored by the Federalist Society, of one of the only four existing manuscript copies of the 1215 Magna Carta signed by King John at Runnymede.

On June 15, we will celebrate the 800th anniversary of Magna Carta, one of the most consequential documents in the history of the law and liberty. It was the basis for establishing the principles that led to the many rights that we take almost for granted today. These include due process of law, the right to a jury trial, freedom from unlawful imprisonment, and the theory of representative government.

While Magna Carta only secured the rights of the barons and “freemen,” as the exhibit carefully explains, “this medieval charter, through centuries of interpretation and controversy, became an enduring symbol of liberty and the rule of law.”

It really is amazing as one walks through the exhibit and reads the translations of certain parts of Magna Carta, to see the principles being outlined that have become such an accepted part of our rule of law 800 years later. For example, Chapter 39 provides no freeman will be seized, dispossessed of his property, or harmed except “by the law of the land,” a phrase that eventually became “due process of law.” This very concept is incorporated in both the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments to the Constitution, which guarantee that no “freeman” in America can be “deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.”

Chapter 39 of Magna Carta guaranteed that no freeman can be punished without “the lawful judgment of his peers.” This principle is the basis for our concept of the right to a trial by jury, which is guaranteed in Article III of the Constitution, as well as the Seventh Amendment.

Magna Carta also guaranteed immunity from illegal imprisonment. This principle led directly to the development of the concept of habeas corpus, the right to sue the government to force it “to produce the body,” an individual who has been illegally imprisoned without due process of law. This was so important that it was incorporated into Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution, which provides that “The Privilege of the Writ of Habeas Corpus shall not be suspended, unless when in Cases of Rebellion or Invasion the public Safety may require it.”

Most importantly, Magna Carta established the principle of the rule of law and checks on the power of the king (the executive in modern parlance). In other words, the concept integral to our own republic that no man is above the law, not even the president. Chapter 61 of Magna Carta stipulated that 25 barons would be selected to ensure that King John complied with the terms of the charter and if he violated the terms, they had the authority to “distrain” the king (seize his properties) until he complied. That principle became a “symbol of the supremacy of the law over the will of the king.”

King Edward I’s 1297 reaffirmation of Magna Carta (a copy of which is on display at the National Archives) said that any act of the king violating the charter “should be undone and holden for naught.” This fundamental principle was incorporated into the entire structure of our system of government as outlined in the checks and balances inherent in the Articles of the Constitution. And what King Edward I said must be done is exactly what the Supreme Court of the United States does when the president exceeds his authority, as evidenced by its recent decision in National Labor Relations Board v. Canning, in which the Court held that President Obama’s recess appointments to the NLRB were unconstitutional. Thus, the president’s action was “undone and holden for naught.”

Two of the people in Washington who might learn the most from visiting this exhibit and its explanation of the importance of the rule of law and the limits on the power of the executive are President Obama and Attorney General Eric Holder. Unfortunately, as two of my Heritage Foundation colleagues explain in a recent paper, “abusive, unlawful, and even potentially unconstitutional unilateral action has been a hallmark of the Obama Administration.”

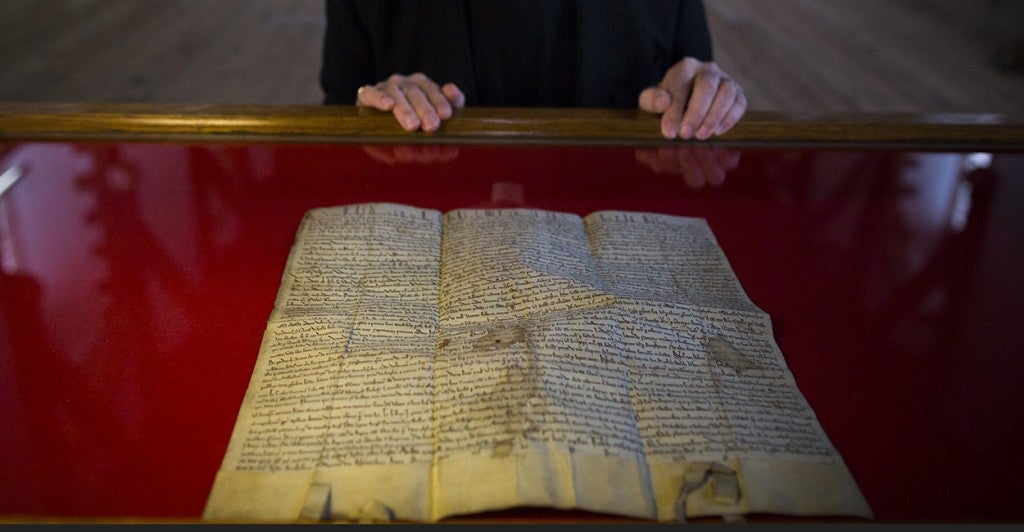

The exhibit at the Library of Congress displays the Lincoln Cathedral Magna Carta, which has been in the possession of the Lincoln Cathedral literally since its issuance in 1215, a concept a little hard for Americans in our relatively new country to quite comprehend.

This is not its first appearance in the United States. It actually came to America in 1939 for the New York World’s Fair. When the fair closed in October 1939, one month after the start of World War II in Europe, Great Britain was concerned about losing Magna Carta if it was shipped back. So Lord Lothian, the British ambassador, deposited Magna Carta in the Library of Congress for safekeeping during the war (it was actually stored, unbeknownst to the British government, at Fort Knox along with our gold supply). It was not returned to Lincoln Cathedral until 1946.

As the exhibit says, “History has not been kind to King John,” who reigned from 1199 to 1216. Neither has Hollywood. The evil, villainous Prince John was played memorably by Claude Raines in “The Adventures of Robin Hood,” the classic 1938 swashbuckler starring Errol Flynn and Olivia de Havilland. Despite his ruthlessness, King John managed to lose the extensive realm his father, King Henry II, had ruled in France and nearly bankrupted England with his high taxes, something the 1938 movie got right in its portrayal of John’s greed. His barons revolted, claiming that the king was acting arbitrarily and disregarding their traditional privileges. The barons seized London after King John ordered the seizure of their castles, bringing the confrontation to a climax at Runnymede, a meadow on the Thames halfway between London and Windsor Castle, on June 15, 1215. Forty-one official manuscript copies of Magna Carta, on which King John placed his seal, were sent to each English county, including Lincoln.

The exhibit and accompanying brochure at the Library of Congress, whose interior is one of the most beautiful buildings in Washington, goes through the history of Magna Carta. That includes King John’s attempted voiding of the charter and the resulting civil war, as well as its reissuance and reaffirmation by subsequent English kings and Parliament. It shows how its principles were incorporated into the charters and laws of the new colonies in America, including “The Body of Liberties” compiled by Nathaniel Ward in Massachusetts in 1641 that “contained a synopsis of Magna Carta’s guarantees of freedom.” These principles profoundly influenced our American founders, who considered them the basic rights to which Englishmen were entitled, and were eventually incorporated into our Constitution and Bill of Rights.

The Lincoln Magna Carta is complete, and although the writing is very small, many parts of it are still legible. Of course, to understand it, you have to read Latin, which is the language in which the charter was written. King John’s seal is missing, although the three holes showing where it was attached are there.

Finally, I have to note that on the way into the room where Magna Carta is housed, one passes by another room where the remains of Thomas Jefferson’s original library are stored. After the British burned the Capitol in 1814, the Library of Congress bought Jefferson’s entire personal collection of books to restore its collection. It is something to peruse the titles of these books and contemplate the wide variety of subjects that interested one of our greatest statesmen, who may have been the best read man in the colonies. And Jefferson’s personal copy of the Federalist Papers is in the Magna Carta display, quite a thrill for a Federalist Society member like me.

This is a great exhibit and one worth seeing if you are in Washington or you can see a digital version here. Magna Carta will be on display until Jan. 19 if you want to see the document that started it all, whose “most lasting legacy is its role in the constitutional tradition of safeguarding individual liberties under the rule of law.”