As thousands of protestors flood downtown Hong Kong in opposition to Beijing’s efforts to control the political future of the “Special Administration Region,” there is growing concern about how this situation will be resolved.

For the people of Hong Kong, the issue is straightforward. Under the terms of the Basic Law, negotiated between the People’s Republic of China and the British government when Hong Kong was still a colony, the PRC committed itself to preserving the institutions that had made Hong Kong such a success—a free press, an independent judiciary, civil liberties and a civil society—for the half-century after reversion in 1997.

This program of “one country, two systems” was touted not simply as a means of ensuring the continued prosperity of Hong Kong, but also as a bellwether for the possibility of eventual application to Taiwan.

Because Hong Kong had not held elections while under British rule (a hypocritical point from Beijing’s perspective), how the territory’s chief executive would be selected had to be addressed in the Basic Law. A gradual transition was agreed upon, wherein Hong Kong would implement a policy of universal suffrage over time to elect a chief executive.

In 2014, in preparation for the scheduled 2017 elections, the universal suffrage plan was unveiled. Beijing held to the letter of the agreement—there would be elections for a chief executive where all the eligible citizens of Hong Kong could vote, but the range of possible candidates would have to pass muster from Beijing.

The situation was exacerbated when Beijing issued a white paper on Hong Kong which essentially undermined the Basic Law governing Hong Kong. The paper reaffirmed the policy of “one country, two systems,” but it emphasized that “as a unitary state, China’s central government has comprehensive jurisdiction over all local administrative regions, including the HKSAR [Hong Kong Special Administrative Region].” The message was clear: –Hong Kong would be allowed to choose among a range of candidates that Beijing approved, and Beijing had no intention of compromising on this.

The resulting outrage among many citizens of Hong Kong led to a student walk-out and protests, which the authorities responded to with tear gas, pepper spray and police mobilization. When that failed to disperse the crowds, the Hong Kong police force largely pulled back. The question is what happens when Hong Kong returns to work on Thursday after Chinese National Day.

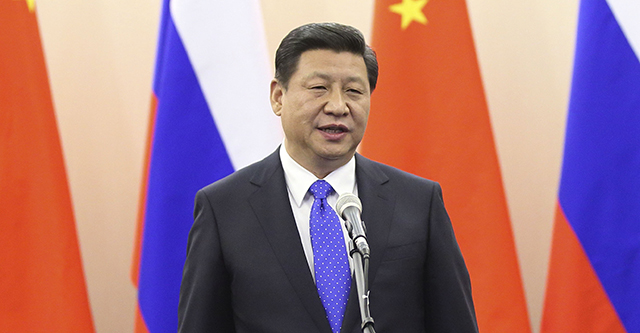

Few expect the Chinese authorities (as opposed to C.Y. Leung and the Hong Kong authorities) to back down. It is important to recognize that Chinese President and Chinese Communist Party General Secretary Xi Jinping is still in the midst of his power transition. As the first Chinese leader to have assumed power without the blessing of a revolutionary era leader, such as Mao Zedong or Deng Xiaoping, his political legitimacy within the CCP is more suspect than any of his predecessors. Moreover, his sustained anti-corruption drive has undoubtedly alienated many within the CCP (aggravated by the likelihood that many of those charged were probably targeted as much for being political rivals and threats as for actual corruption).

The Hong Kong White Paper and the resolution of the Chinese National People’s Congress Standing Committee both reiterated that Beijing has every right to keep Hong Kong in line, which gives him little room to compromise, even assuming he wants to do so.

On the other hand, Hong Kong is one of the world’s major financial centers. Anything that destabilizes the territory or undermines its credibility would jeopardize that position. As a major financial center, moreover, Hong Kong remains a central source of foreign direct investment into China, providing more than half of the amount invested in 2013. It has also been a major source of equity financing, whether in terms of initial public offerings for companies, bonds, or loans.

If China truly wishes to challenge the United States for global financial leadership, it will have to rely on a healthy Hong Kong to provide the expertise and trained personnel—and demonstrate that it is willing to let the city function independently, and not simply as a branch of the Chinese Communist Party.

Moreover, as noted earlier, Hong Kong is seen as a test case for relations with Taiwan. An unsatisfactory resolution of the situation, never mind a bloody one, would cripple cross-straits relations, just before the 2016 elections on the island, when neither the Kuomintang or the Democratic Progressive Party will be fielding an incumbent. An abject failure of “one country, two systems” in Hong Kong likely would benefit the DPP, which has solidly supported independence.

Finally, the experience of Tiananmen Square 25 years ago is not one that the Chinese leadership likely wants to repeat. While China’s grip over its Internet and social communications may limit the word of any bloody suppression of Hong Kong, the rest of the world is much more connected than it was in 1989. The ongoing Tiananmen sanctions limiting high-tech trade would likely only be strengthened in the event Beijing orders a violent crackdown.

For Xi Jinping, the next few weeks will likely be among the most momentous and crucial of his time in office.