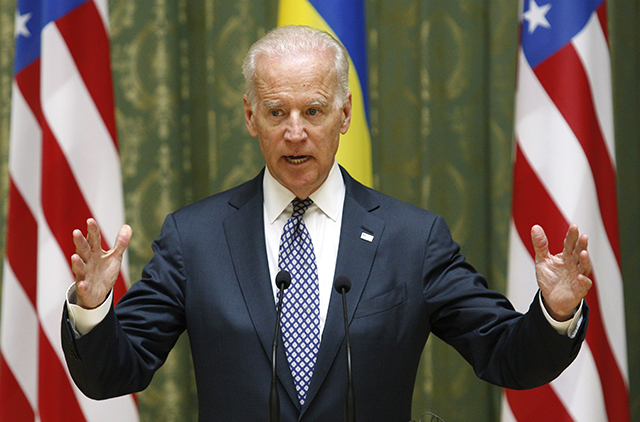

Vice President Joe Biden, who went to Ukraine on Monday for a two-day visit to express U.S. support for the government in Kyiv, has accused Russia of being behind the irregular armed forces who are taking over Eastern Ukraine. However, he did not offer much beyond $50 million in assistance to fight corruption. The U.S. also promised to send a symbolic force—four companies of paratroops—to the neighboring NATO countries over the next several months—hardly a deterrence.

The time for symbolic gestures has passed, however. There is a consensus that Russia’s special forces (spetznaz)—wearing unmarked uniforms—are orchestrating violent separatist activities in Eastern Ukraine. Biden warned Moscow that it would face further sanctions and isolation if it continues interfering in Ukraine. Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev rebuffed American threats and said that sanctions would only make the Russian economy stronger.

Signed on April 17, the Geneva accords failed to defuse the tense situation in Eastern Ukraine. The agreement called for all illegally occupied administration buildings and street squares in the Russian-speaking Donbass region of Ukraine to be vacated. Instead, Russian-controlled paramilitaries are refusing to abandon government buildings in at least nine towns in the Donetsk region.

Bearing markings consistent with extreme torture, the bodies of two men, including Volodymyr Rybak, a deputy from the ruling Batkyvshchina (Fatherland) party, turned up near Slavyansk. Ukrainian authorities are blaming the pro-Russian forces for the kidnappings.

The fragile Geneva truce was broken on Easter Sunday, just three days after it was signed. An armed confrontation between Russian-controlled armed gangs and pro-Ukrainian groups took place at a checkpoint outside of Slavyansk and, in the ensuing struggle, three men were killed.

Moscow and Kyiv each blamed the other for the incident: Kyiv called the clash a provocation, staged by Russian Special Forces, while Russian Foreign Minister Lavrov accused Kyiv of failing to protect ethnic Russians from the ultra-nationalists, further raising fears that Russia might invade.

Last Thursday, President Putin, in televised Q&A with the nation, acknowledged that Russia used its special forces in the Crimea before the referendum on March 16—a claim Russian authorities had previously denied.

Putin used the old imperial name for Eastern Ukraine, “Novorossiya,” or New Russia, implying the possibility of occupation and annexation, and has also invoked the powers granted to him by the Russian rubber-stamp parliament to use force against its Eastern Slavic neighbor. Putin also claimed that the Government of Ukraine, which Joe Biden is dealing with, is illegitimate.

There is no sign that the situation in Ukraine will deescalate any time soon. This Monday, for example, armed militants in Kramatorsk seized the police headquarters building. There are reports that pro-Russian separatists are intimidating, harassing, and kidnapping journalists, including the American Simon Ostrovsky.

While Western powers are calling on Russia to deescalate and remove its troops from the border, it is clear that Moscow wants to destabilize Ukraine, bring parts of that country under Russia’s control, and prevent from joining NATO and the EU. Other post-Soviet countries may also be in Vlad’s crosshairs.

So far, Putin’s annexation of Crimea has been met with a weak response from the West, while boosting his domestic popularity. Unless the U.S. and the West find the right combination of sanctions and coercive diplomacy, there is little chance that Moscow will turn back from the path of intimidation, intervention, and aggression against its neighbors.