Paul Krugman, in the words of a former New York Times public editor, “has the disturbing habit of shaping, slicing and selectively citing numbers.” Most recently, he selectively cited numbers about austerity in Europe, hoping to redefine the policies that made the German economy so buoyant.

Germany is worth paying attention to: It has enjoyed steady growth since the global recession. In fact, The Heritage Foundation is working on an extensive report on Europe’s experience with spending, taxes, and austerity.

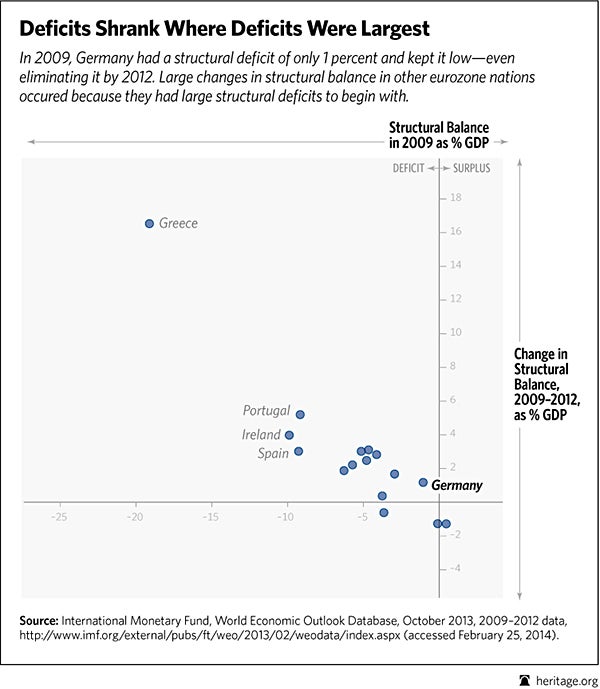

Naturally, Krugman wants to make Germany a paragon of Keynesian economics. He notes that Germany has barely narrowed its structural deficit since 2009. (A structural deficit is a way of measuring budget deficits that tries to account for the business cycle.) By contrast, Greece rapidly shrank its structural deficit and had a depression. Blame the austerity, Krugman concludes.

But the data tell a simpler story: The reason Germany did not shrink its structural deficit is that Germany barely had a structural deficit! In 2009, Germany’s structural deficit was just 1 percent of gross domestic product. Greece’s deficit was 19 percent. In fact, across eurozone countries, the change in structural balance from 2009 to 2012 is largely predicted by the size of 2009 deficits—the bigger the deficit, the harder they fell.

That’s a problem for the Keynesian story. According to Krugman’s Keynesian model, government can stimulate aggregate demand by running large deficits in bad times, softening the recession. If government fails in its duty to borrow, the recession will mire on.

Greece was the apotheosis of Keynesian stimulus—spending for spending’s sake, lax tax collection, and a government committed to borrowing at the low prevailing interest rates. And Greece was not the exception; it was just the extreme. The next largest deficits were in Ireland, Spain, and Portugal, which had miserable growth. The eurozone experience since 2007 does little to commend Keynesianism.

What did the Germans do that put them in a position for growth right after the recession? Back in 2001, Germany and Greece had the same structural deficit—just above 3 percent. But Germany shrank its deficit from 2004 to 2008 by cutting spending on welfare, unemployment insurance, and pensions. These cuts did double duty as “structural reforms” by reducing government influence in the economy and making the labor market more competitive. Krugman thinks structural reforms are a distraction despite their vital role in making the German economy more free and resilient. Despite heavy banking losses, Germany’s recession was relatively mild, and the country did not vastly expand its structural deficit as the U.S. and many others did. As a consequence, it did not need to adjust its finances after the recession.

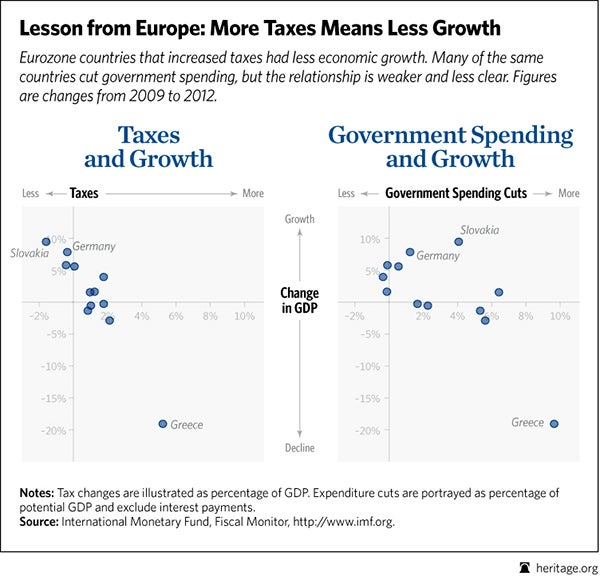

The real secret to “austerity” is that it can mean either spending cuts or tax increases. Guess which one Germany did after the recession.

(Wonkish note: I used 2012 structural balance because 2013 data were still projections, but it makes little difference.)

One Reply to “Paul Krugman: Selective Data Usage”