As we honor the leadership and vision of President Reagan on his birthday on February 6, it is essential to recognize his unshakeable commitment to strengthening the military power of the United States.

He saw this strength as necessary to preserving security, stability, and ultimately peace in the world, and it was undergirded by his confidence in the goodness of the American people and the American nation.

Prior to Vietnam, American foreign policy was divided between realists and idealists. Realists believed that the U.S. needed to exercise restraint in furthering its fundamental principles of liberty and democracy in the conduct of its foreign policy—most particularly when it involved the application of military force. They saw unbridled engagement leading to the U.S. undermining its moral standing by lowering itself to the power politics practiced by the nations of Europe in particular. The idealists, on the other hand, believed in an energetic foreign policy that accepted the expenditure of considerable blood and treasure, not to mention political capital, to further American principles abroad. They saw robust international engagement as an affirmation of American ideals and leading the rest of the world in the direction of raising its standards to the level of the United States.

These contending ideologies over foreign policy, however, shared an essential belief: a moral confidence in the U.S. as a nation founded on an idea, which made it an exceptional nation on the world stage.

The Vietnam War shattered this fundamental consensus and led to a new dividing line: between those with a sense of moral confidence in the U.S. and its exceptional status and those who were skeptical about the moral standing of the U.S. relative to other nations.

The forces of moral self-confidence naturally saw robust military capabilities and the willingness to use them as a force for security, stability, and peace. The forces of moral self-doubt thought that those same capabilities could or would be used for questionable purposes and lead to less security, instability, and perpetual war.

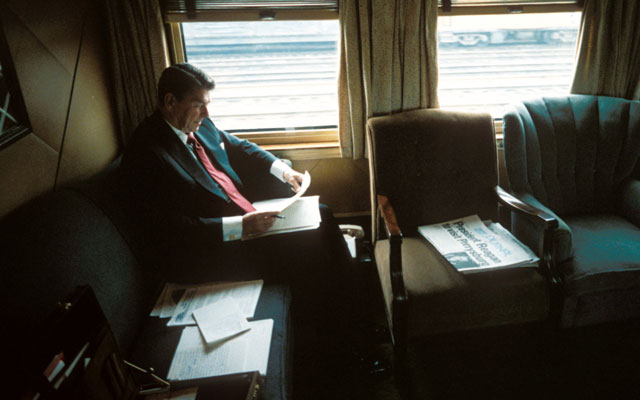

President Reagan was unquestionably one of the foremost leaders of the forces of moral self-confidence. When he assumed the presidency in 1981, he set about fulfilling his commitment to strengthen the military forces of the U.S. His critics argued against the increased funding for the military and the arming of freedom fighters in places such as Nicaragua in favor of a nuclear freeze with the Soviet Union.

Fast forward to today, and one sees that the same dividing line in the debates over foreign and military policy that emerged following Vietnam endures. In this case, however, the presidency is in the hands of one of the foremost leaders of the forces of moral self-doubt. President Obama first ran for President in 2008 by appealing to constituencies that labeled President George W. Bush a war criminal, asserted that the U.S. undertook Operation Iraqi Freedom in order to confiscate Iraqi oil, and derided the policy for constructing a defense of the U.S. against missile attack.

Following the 2008 election, President Obama undertook an apology tour. Now, with his re-election campaign behind him, President Obama is setting about the task of shrinking and weakening the military.

President Reagan, if he were here today, would recognize both how wrong-headed President Obama’s foreign and defense policies are and what drives these policies. He would fight them tooth and nail. As he did in the late 1970s and 1980s, he would argue that the U.S. is a force for good in the world and that a robust military force would lead to security, stability, and peace.

As usual, President Reagan’s vision gives hope and confidence to the American people, just as the American people can give hope and confidence to the world at large. However, there is precious little hope or confidence either at home or abroad today.