A New York Times editorial published in the midst of Hurricane Sandy’s devastation has received a good deal of attention. The article argued that “A Big Storm Requires Big Government,” politicizing and distorting calls for reform of the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA). A response by The Wall Street Journal, however, sought to set the debate straight.

While the Times tried to argue that conservatives essentially want to eliminate FEMA and place disaster response solely in the hands of the states, the Journal wrote:

This isn’t an argument for abolishing FEMA so much as it is for the traditional federalist view that the feds shouldn’t supplant state action. As it happens, the response to Hurricane Sandy has been a model of such a division of responsibility.

Citizens in the Northeast aren’t turning on their TVs, if they have electricity, to hear Mr. Obama opine about subway flooding. They’re tuning in to hear Governor Chris Christie talk about the damage to the Jersey shore, Mayor Mike Bloomberg tell them when bus service might resume in New York City, and Connecticut Governor Dannel Malloy say when the state’s highways might reopen.

The issue is not that the federal government shouldn’t have a role in disaster response. Indeed, as Heritage’s Matt Mayer explained:

No conservative I know wants to eliminate FEMA or the federal role in disaster response and recovery. The fact is, conservatives have been consistently advocating for the decentralization of those functions for routine natural disasters to states and localities to ensure that FEMA is prepared to deal with truly catastrophic events that hit America—like Hurricane Sandy.

In fact, the Journal actually cited Mayer on this exact point, as well as his figures documenting how federal disaster declarations have skyrocketed over the past two decades:

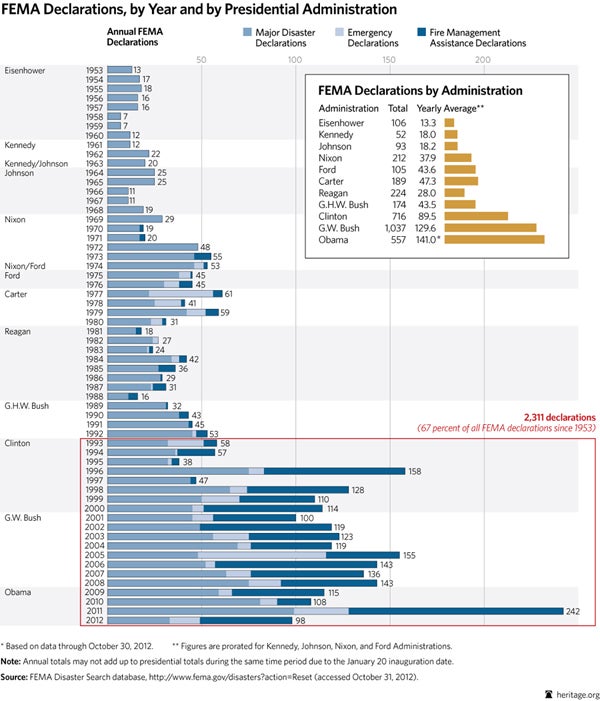

[A]nnual FEMA disaster declarations have multiplied since the Clinton years and have reached a yearly average of 153 under Mr. Obama. That compares to 129.6 under George W. Bush, 89.5 under Mr. Clinton, and only 28 a year under Reagan.

What this means is that FEMA is responding to more and more routine disasters such as tornadoes, fires, floods, snowstorms, and severe storms—with little to no regional or national impact. As a result, FEMA’s resources are getting stretched thin, making the agency ill-prepared to respond to a large-scale, catastrophic disaster. Meanwhile, state and local governments, becoming used to the federal government swooping in and picking up the check, have begun to trim their own emergency response budgets. (continues below chart)

When a disaster like Hurricane Sandy truly overwhelms the capabilities of state and local governments, the federal government should be prepared to help. After all, the federal government can best organize and leverage national resources and call on the Defense Department and National Guard for help. But when FEMA is forced to respond to disasters on the scale of one every one-and-a-half days, it has no time to prepare.

Federalism has long been the guiding principle for allocating responsibilities to meet the needs of citizens after disasters. Hurricane Sandy should serve as a reminder of this principle, not an opportunity to abandon it.