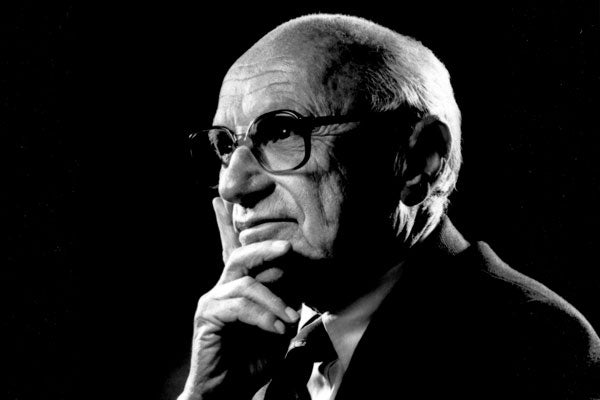

Let us imagine we have the power to rebuild our education system from the ground up—an appropriate mental exercise as we remember the late Nobel Prize–winning economist Milton Friedman on his 100th birthday tomorrow.

If we could rebuild our education system from scratch, it’s unlikely we would create a system that assigns children to government-run schools based on their parents’ zip codes. After all, geography and income shouldn’t determine a child’s educational opportunity. If we rebuilt our education system to reflect Friedman’s philosophy, parents would be free to choose an education that best met their children’s needs, with money following the children to any schools of their choice: public, private, charter, virtual, or home school.

Friedman pioneered the idea of educational vouchers, and more than a half century later, that vision is taking hold at a rapid pace. State leaders across the country are making school choice a reality for hundreds of thousands of American families. In 2011 alone, 13 states enacted or expanded school choice programs, prompting The Wall Street Journal to deem 2011 “The Year of School Choice.”

Arizona enacted groundbreaking education savings accounts, Indiana created the largest voucher program in the country, and the highly successful D.C. Opportunity Scholarship Program was reauthorized.

While school choice momentum has been building dramatically in the last two years, most children still attend assigned public schools. For too many families, school choice remains out of reach.

Poor families are most affected by this lack of choice. As Friedman noted, “There is no respect in which inhabitants of a low-income neighborhood are so disadvantaged as in the kind of schooling they can get for their children.” It is a sad statement quantified by data on low levels of academic achievement and attainment.

In Denver, just 44 percent of students graduate. In Philadelphia, a mere 46 percent of students complete high school. And in Detroit, just 33 percent of children graduate.

And if they are persistent enough to graduate, what have they learned? Nine percent of Baltimore fourth-graders are proficient in reading. Just 11 percent of their eighth-grade peers can read proficiently. A devastating 7 percent of Cleveland fourth-graders are proficient in reading. In Detroit, just 6 percent can read proficiently.

These low levels of academic achievement and attainment aren’t confined to low-income students or urban school districts. Across the country, for all children, just one-third can read proficiently. Graduation rates have hovered around 74 percent since the 1970s, and math and reading achievement has been virtually flat over the same time period. On international assessments, American students rank in the middle of the pack, outperformed in math by the Czech Republic, Slovakia, and Estonia.

Friedman had a strong belief in the power of markets to improve education, and he didn’t mince words about school choice: We will only see improvements in education, he said, “by privatizing a major segment of the educational system—i.e., by enabling a private, for-profit industry to develop that will provide a wide variety of learning opportunities and offer effective competition to public schools.”

That’s certainly going big on school choice. But what exactly did Friedman mean by “privatizing a major segment of the educational system”? Just because we have agreed to the public financing of education does not mean government should be the sole provider of that education and dictate where children go to school.

As we remember Friedman on his 100th birthday, we need to rethink what “public” education means, thinking instead in terms of educating the public, not in terms of government-run schools—that is, as publicly financed but operated by many different providers. If we consider public education in those terms, we can start to think through funding mechanisms at the state level that will bring about widespread school choice.

Today, we have a growing number of innovative school choice options—charters, vouchers, tax credits, online learning, and education savings accounts, to name a few. These options were conceived in the mind of Friedman and are being brought to life by reform-oriented governors and legislators across the country.

While these reforms have been a long time in the making, Friedman would no doubt be proud of the progress that has been made on school choice over the past few years. And thanks to his formational work, children across the country are increasingly gaining access to customized education that meets their unique needs.