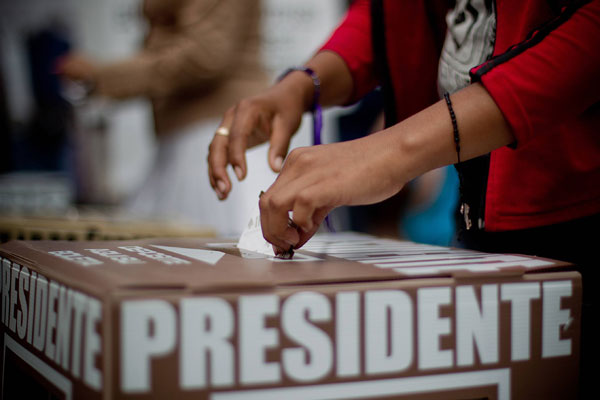

The Mexican elections that occurred on Sunday will be closely scrutinized and intensely analyzed after 49 million of Mexico’s 80 million registered voters went to the polls to select a president for a single six year-term (2012–2018), 128 senators, 500 deputies, and six governors, as well as the mayor of Mexico City.

History books mark the 2000 elections as the major turning point ending the 70-year rule of the Revolutionary Institutional Party (PRI) with election of Vicente Fox, candidate of the center-right National Action Party (PAN). This politically seismic event ushered in an era of modern democracy in Mexico.

Now, after Sunday’s voting, the PRI’s telegenic, 45-year old former governor of the state of Mexico, Enrique Pena Nieto, is the projected winner, capturing an estimated 38 percent of the vote. His nearest rival, leftist Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (Democratic Revolutionary Party), won 31 percent, while Josefina Vazquez Mota, from the incumbent PAN of outgoing president Felipe Calderon, gained 25 percent.

Few tears were shed when the PRI’s “perfect dictatorship” ended more than a decade ago. Its apparent return in 2012 is viewed more with caution than with visceral fear. The PRI claims that it has changed and offers a path for “responsible change” with reforms that could include a serious opening of Mexico’s energy sector to foreign investment, expanding competitiveness, shaking up the educational system, and implementing fiscal and labor reforms.

Mexico’s new leadership will also re-evaluate the strategies President Calderon pursued in a war on organized crime and drug trafficking that has resulted in more than 55,000 homicides in the past six years.

The nearly five months from the July elections to the December inauguration of the next Mexican president are a chance to review, evaluate, and build a constructive bilateral agenda. This is too important a period to let U.S.–Mexico relations languish on the backburner during the U.S. presidential campaign.

One Reply to “Mexico: Elections That Truly Matter”