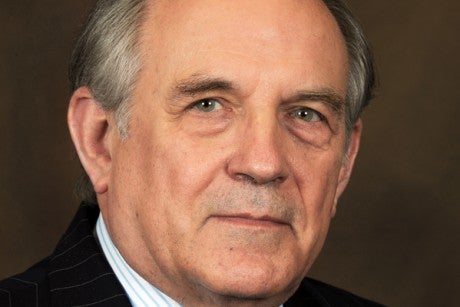

Last week, Charles Murray of the American Enterprise Institute spoke to an audience at The Heritage Foundation about his latest book, Coming Apart. Murray warned of a gap in culture and values that has steadily increased throughout the last 50 years between upper-class (defined as those having at least a college education) and lower-class (those with a high school degree or less) white Americans. When viewed through the prism of the values that our nation’s Founders deemed essential to self-governance—marriage, religion, industriousness, and honesty—trends of the last five decades give evidence that a once-common civic culture is unraveling.

Murray explains that, although cultural changes in the 1960s that challenged these virtues were widespread, those within the highly educated professional and managerial “upper class” were equipped to change course and re-establish the lost virtues and values. Meanwhile, the life decisions of those in the lower class continued a downward spiral toward disintegration.

One of the greatest divides that has emerged between upper- and lower-class America is the dramatic difference in marriage rates. As Murray notes in Coming Apart, in the 1960s, marriage rates between upper- and lower-class Americans were fairly similar, 94 percent compared to 84 percent. While the marriage rate among the upper class has declined somewhat since that time, to about 84 percent, it has plummeted to only 48 percent among those in the lower class.

The economic implications of this trend are substantial. The institutions of marriage and intact families have ramifications for individuals and society ranging from financial security and asset development to physical and emotional well-being. Additionally, the decline in marriage is coupled with a major growth in unwed childbearing, the greatest predictor of childhood poverty.

Strong and stable marriages have a ripple effect in society: An intact family structure is linked to children’s academic achievement and educational attainment, which, in turn, promotes industriousness.

The trend toward less religiosity among lower-class America weakens the role that religious practice plays in engendering a healthy civic culture. As Murray points out in his book, “Religion’s role as a source of social capital is huge.” Decades of research, available on Heritage’s Family Facts website, support the validity of this statement. Church attendance is associated with an increased likelihood of charitable giving, volunteerism, and civic involvement. Church attendance is also associated with the virtue of honesty, including marital fidelity.

Sadly, as Murray points out, in a social climate that is imbued with a sense of relativism and an aversion to judgment, members of the upper class are reluctant to “preach what they practice”—i.e., what Murray calls the “founding virtues” of industriousness, honesty, marriage, and religion. Promoting the revitalization of essential civic virtues is to pass along the keys to a life of fulfillment, well-being, and prosperity.