In 5 Charts, Factors Affecting China’s Military Future

Brent Sadler / Jackson Clark /

China launched missiles over Taiwan and into Japanese waters in a truculent response to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi’s Aug. 2 visit to the island nation.

That was just the latest sign Beijing is not deterred and might be closer to trying a military takeover of Taiwan than most believe. Given how long it takes to build modern naval warships, the U.S. needs to start building now if it is to have the fleet it will need to deter Chinese aggression.

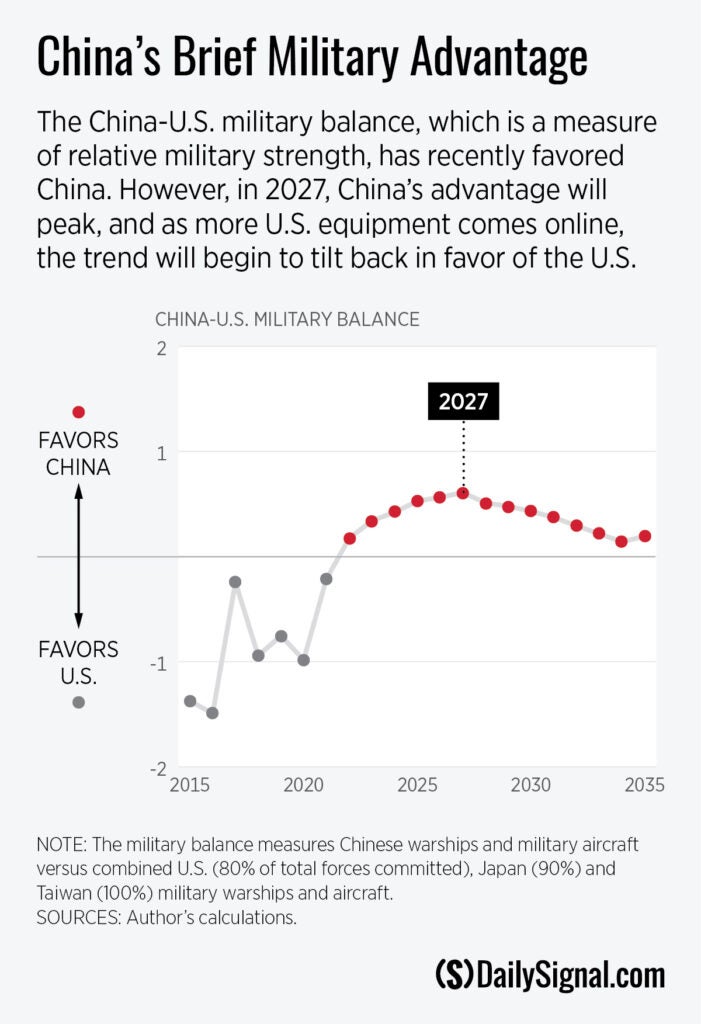

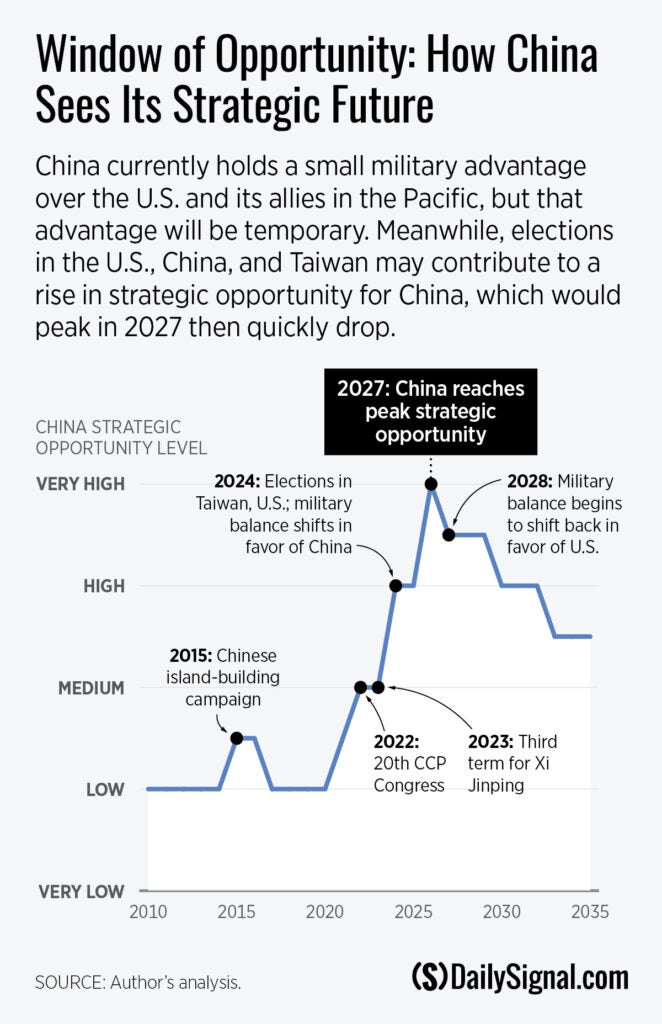

Last year, Navy Adm. Phil Davidson, the former commander of the U.S. Indo-Pacific Command, cautioned Congress that China is preparing to move against Taiwan by 2027. That assessment is shared by the current Indo-Pacific commander, the current CIA director, and Mike Pompeo, a former secretary of state and ex-CIA director.

Why 2027? Eyeing negative economic and demographic trends, and the regional military balance, Chinese leaders worry that the odds they’ll be able to achieve their long-held goal of conquering Taiwan will fade with each passing year after that.

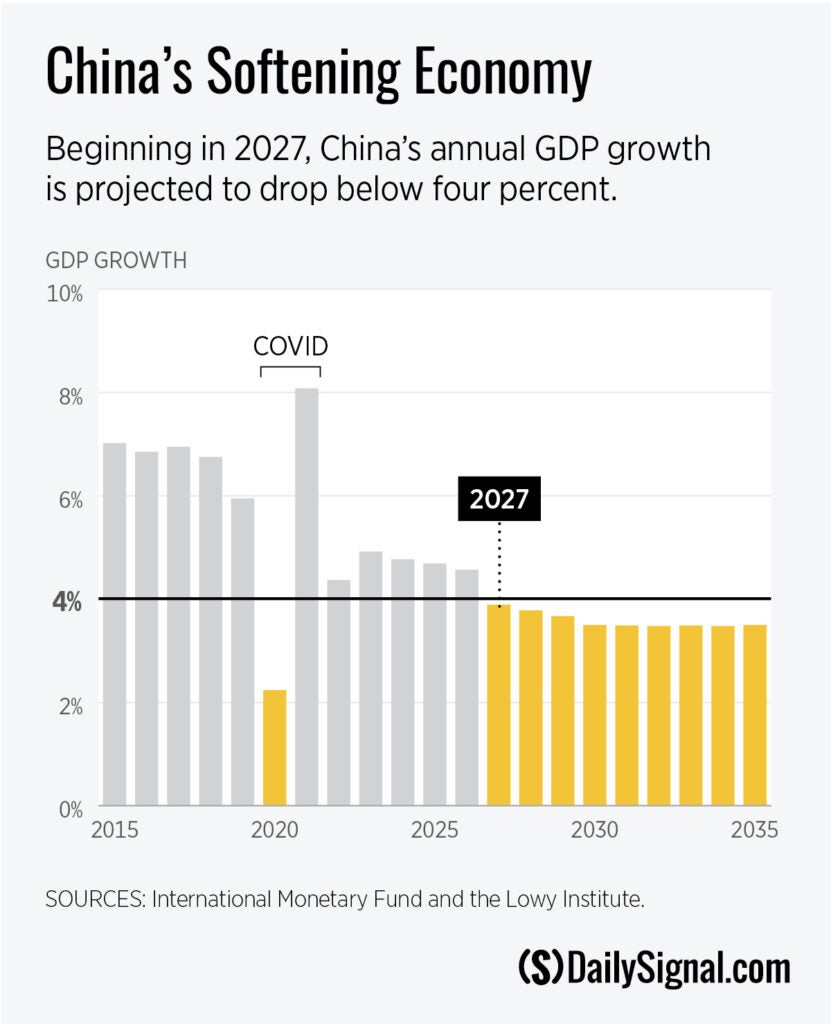

The Chinese Communist Party promised prosperity in exchange for party dominance, and it delivered decades of breathtaking economic growth—until recently.

A seemingly endless supply of cheap labor allowed China to become the world’s factory, raking in huge profits. That also enriched the party, which was then able to fund massive military programs and conduct nefarious debt diplomacy to buy access to overseas ports and markets.

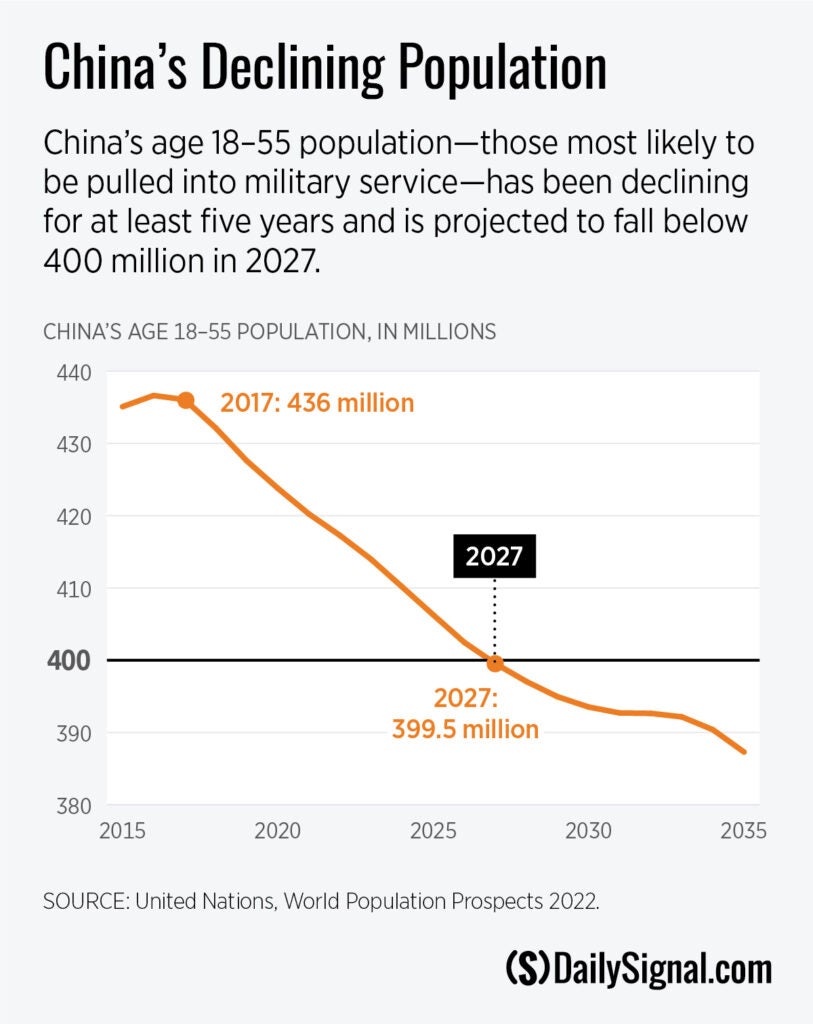

But China’s one-child policy created a looming population crisis, and already its pool of able-bodied workers is shrinking. On top of that, the economy faces added pressure from the regime’s disastrous COVID-19-zero policies and a looming global recession.

Beijing is accused of misreporting economic growth and demographics to present a false picture of strength and resilience. However, that facade will crumble as the population declines, driving up labor costs and halving gross domestic product growth rates by decade’s end.

A shrinking population will also inhibit China’s continuing military expansion.

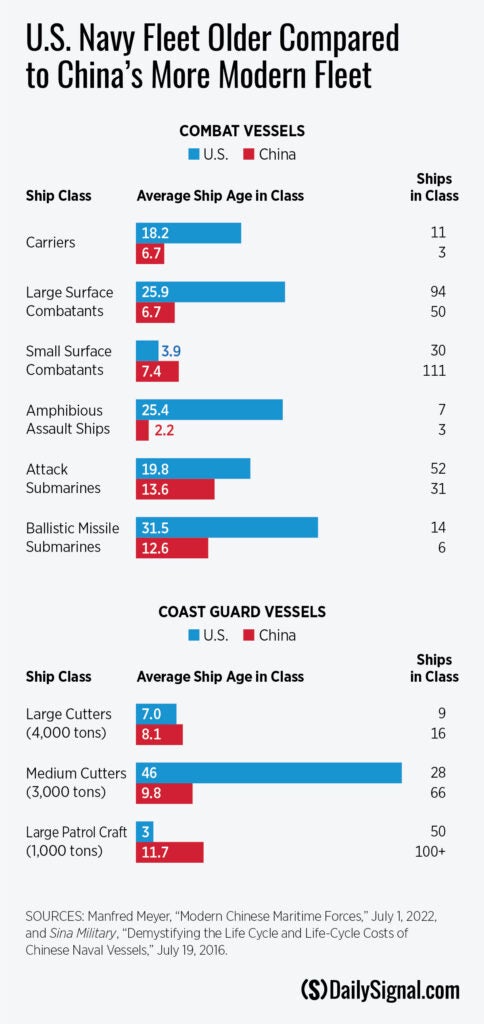

In 2016, China’s navy surpassed the U.S. Navy as the largest fleet in the world. The Chinese navy has since continued to grow, while ours has shrunk. The Chinese fleet is modern and lethal, with everything from nuclear missile submarines to supercarriers.

But most of that fleet will reach its 30-year life span at this decade’s end. Then, Beijing will have to decide whether to extend the ships’ service lives or continue its high-capacity shipbuilding program.

Demographic and economic pressures will make both options problematic.

Further confounding Chinese military planners are increasingly well-armed neighbors. Japan is on track to break its self-imposed 1% GDP limit on defense spending. The newly created AUKUS (Australia-United Kingdom-United States) pact portends the addition of Australian nuclear submarines to the region. And South Korea, Taiwan, and the Philippines have all increased their defense spending past that of many NATO members.

As economic, demographic, and military balance pressures build, effective deterrence of Chinese military adventurism this decade will require several things.

First, the U.S. and its allies must present Chinese President Xi Jinping with an unfavorable military power balance. Building new ships, planes, and increasing supplies of advanced munitions would send an unmistakable message to Chinese Communist Party leaders that success in an invasion of Taiwan cannot be assured.

That won’t be easy. The U.S. is no longer the arsenal of democracy it once was. Economic and industrial vulnerabilities include inadequate commercial shipping to sustain a wartime economy, too few logistics ships to sustain military operations, and a shipbuilding industry too small to maintain today’s fleet, let alone build a larger one.

Unless we move quickly to address those weaknesses, Chinese leaders might well calculate that they could outlast the U.S. in a long war—if they strike sooner rather than later.

The U.S. has overcome such weaknesses before, most notably with the Naval Act of 1938 that directed a just-in-time 20% growth of the fleet. That act is credited with preparing the nation for the war in the Pacific in World War II.

Second, the U.S. must keep the pressure on while assisting Taiwan to keep scaling up its military budget and investing in asymmetric weapons to deter a Chinese invasion.

Finally, the U.S. must continue to sow doubt among the senior Chinese Communist Party leadership that they will be able to achieve their political objectives through force.

One clear way to do that would be by better positioning and operating U.S. military forces in the region to confound Chinese military planning.

China might well regard this decade as offering a limited strategic window of opportunity for taking Taiwan. Washington has little time to avert disaster and close the current U.S. window of vulnerability.

It takes years to build up navies, so delay is not an option. Now is the time to put action and money toward rebuilding the nation’s deterrence capability. That’s a language the Chinese Communist Party understands.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email [email protected] and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the url or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.