The Ideology of Isolationism

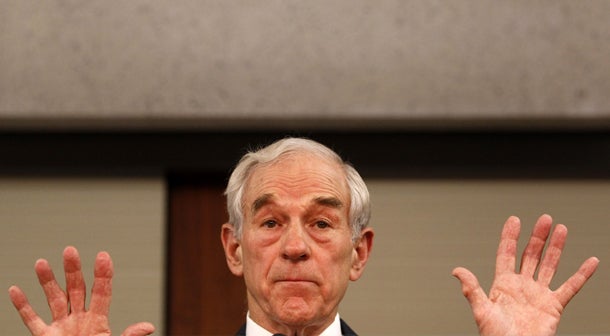

Supporters of Ron Paul have re-launched an old ad promoting the old idea of American isolationism. “We now are a nation known to start war,” Paul is quoted as saying. “We feel compelled because of our insecurity that we have to go over and attack these countries to maintain our empire.” The message here (and repeated elsewhere) is that Paul’s isolationism is aligned with the Founding Fathers and “what is truly American and truly constitutional.” Not only is this refrain a gross misrepresentation of American history but it offers dangerously misleading guidance to a nation that faces serious challenges at home and abroad.

Following this lead, some are tempted by the myth that our Founders were isolationists who sought to withdraw from the world and focus solely on the home front. At a time of international fatigue and anxiety about America’s future, I understand the sentiment. But it’s simply not the case.

The Founders rejected modern approaches in American foreign policy—whether power politics, isolationism or crusading internationalism. They especially disagreed with the “visionary, or designing men, who stand ready to advocate the paradox of perpetual peace,” as Hamilton put it in Federalist 6. Instead, they designed a truly American foreign policy—fundamentally shaped by our principles but not ignorant of the place of necessity in international relations.

The classic statement of this is Washington’s Farewell Address, sometimes wrongly read as isolationist dogma. Yes, Washington rightly warns us against “the insidious wiles of foreign influence” and yes, Washington correctly states that in extending commercial relations we should have as little political connection with those nations as possible. That’s not isolationism but common sense. Washington goes on to state the objective: “to gain time for our country to settle and mature its recent institutions, and to progress, without interruption, to that degree of strength and consistency, which is necessary to give it, humanly speaking, command of its own fortunes.” And again:

If we remain one people, under an efficient government, the period is not far off when we may defy injury from external annoyance; when we may take such an attitude as will cause the neutrality we may at any time resolve upon to be scrupulously respected; when belligerent nations, under the impossibility of making acquisitions upon us, will not lightly hazard the giving us provocation; when we may choose peace or war, as our interest guided by justice shall Counsel.

Rather than trap themselves in some absolute and permanent doctrine of nonintervention in the world, the Founders advocated a prudent and flexible policy aimed at achieving and thereafter permanently maintaining the sovereign independence for Americans to determine their own fate. And without providing for our own security, how can we hope to control our own destiny or command our own fortunes?

The requirements of security are dictated by the challenges and threats we face in the world. “How could a readiness for war in time of peace be safely prohibited, unless we could prohibit, in like manner, the preparations and establishments of every hostile nation?” Madison asked in Federalist 41.

The means of security can only be regulated by the means and the danger of attack. They will, in fact, be ever determined by these rules, and by no others…. If one nation maintains constantly a disciplined army, ready for the service of ambition or revenge, it obliges the most pacific nations who may be within the reach of its enterprises to take corresponding precautions.

The dangerous ambitions of power were to be found in the passions of human nature. As Hamilton wrote in Federalist 34:

To judge from the history of mankind, we shall be compelled to conclude that the fiery and destructive passions of war reign in the human breast with much more powerful sway than the mild and beneficent sentiments of peace; and that to model our political systems upon speculations of lasting tranquility, is to calculate on the weaker springs of the human character.

Necessity dictates that the United States must be ready to fight wars and use force to protect the nation and the American people. Hence Washington often liked to use the old Roman maxim: “To be prepared for war is one of the most effectual means of promoting peace.” The Founders made sure they were prepared and were not reluctant to use force. How else can we choose peace or war, as our interest guided by justice shall counsel?

National security is a challenge for all nations, but particularly for democratic political systems dedicated to the limitation of power. Many actions necessary for security employ the use of force and proceed in ways that are often secretive and less open than democracy prefers. Likewise, national security sometimes requires restrictions and sacrifices that would be inimical to personal liberty were it not for significant threats to the nation.

The solution to this dilemma is not to deny the use of force or to make it so onerous as to be ineffective. Rather, it is to establish a well-constructed constitution that focuses power on legitimate purposes and then divides that power so that it does not go unchecked, preserving liberty while providing for a nation that can—and will—defend its liberty.

Government spending, its massive bloat and constitutional overreach must be on the chopping block. But the core and undisputed constitutional responsibility of the United States government to provide for the common defense is not up for negotiation.

At a time when we should be seriously thinking about our strategy and commitments anew in an increasingly dangerous world—doing so in the context of unlimited government spending and uncontrolled debt that threatens to force us in to national bankruptcy and undermine our very sovereign independence—we should be wary of claims, however tempting in the moment, that the naïve ideology of isolationism has a place in the pantheon of America’s principles.