What CBO Says About Raising Eligibility Ages for Medicare, Social Security

Emily Goff / Alyene Senger /

Dark clouds hover over the nation’s finances and threaten a perfect storm of massive debt and crushing taxation unless Congress starts acting—soon. Washington must demonstrate that it is serious about reining in ever-rising spending and reducing annual deficits.

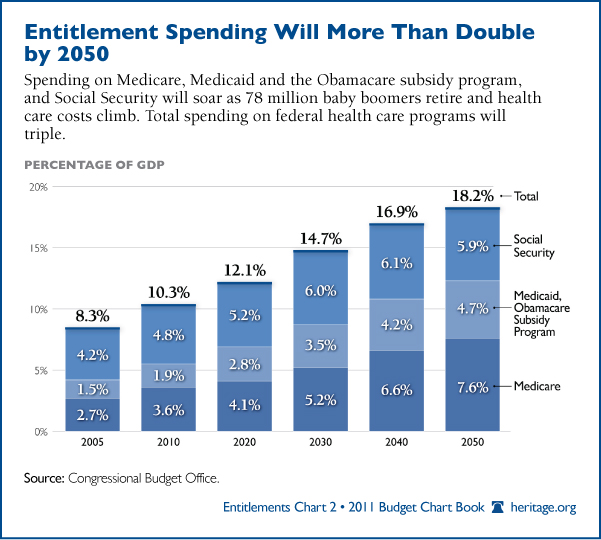

Passing commonsense reforms to our major entitlement programs (Medicare, Medicaid, and Social Security), the main drivers of future spending and annual deficits, is crucial. As the population ages and health care costs rise, spending on entitlements is projected to more than double by 2050, as this Heritage Budget Chart Book chart shows.

Social Security ran a cash flow deficit of $49 billion in 2010, and the 2011 trustees report indicates such deficits will be the norm by 2017. The report also reveals that Social Security’s unfunded obligation stands at $9.1 trillion, in net-present-value terms; in other words, it owes $9.1 trillion more in benefits than it will take in through taxes. The program will experience further financial strain as the worker-to-retiree ratio keeps falling. Medicare faces a 75-year unfunded obligation of $34.8 trillion, in net-present-value terms, and must be reformed if we want to ensure that younger generations have quality health care when they retire.

A Congressional Budget Office (CBO) report released this week examining the effects of gradually raising the eligibility ages for Medicare and Social Security is very timely. The CBO analysis finds that doing so would reduce federal spending on program benefits and encourage people to work longer. This in turn would grow the labor force and total economic output.

The CBO estimates the effects of raising Social Security’s early eligibility age (EEA) from 62 to 64 and normal retirement age (NRA) from 67 to 70. The idea of raising the EEA and NRA is not new, and it claims broader support than other reforms. It also makes sense. As Heritage’s David John has written,

Future retirees will live much longer on average than their grandparents, and Social Security must change to reflect that increased longevity by increasing retirement ages for both full benefits and early retirement benefits. Otherwise, recipients will spend an ever higher proportion of their lives living at the expense of their children and grandchildren.

The CBO report found that a person retiring today at 65 “can expect to spend 30 percent of adulthood in retirement,” or 20 years, while in 1940 that figure was 23 percent, or 14 years. Given that these longevity increases have taken place already, changes to the retirement ages are reasonable if not essential.

Raising the Medicare eligibility age (MEA) is not a revolutionary idea, either. Medicare faces even more funding challenges than Social Security, for many of the same reasons. Raising the MEA proves necessary to stabilize Medicare and reduce its impact on federal deficits.

The CBO’s report finds that gradually raising the MEA from 65 to 67, beginning in 2014, would reduce federal Medicare outlays by $148 billion from 2012 through 2021. It estimates that “by 2035, Medicare’s net spending would be about 5 percent below what it otherwise would be.” Raising the MEA along with the Social Security eligibility ages according to the CBO report’s schedule would cause outlays to fall by 0.4 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) and revenues to increase by about 0.5 percent of GDP by 2035. That makes for a 1 percent budget deficit reduction. Not huge, but it’s a step in the right direction.

If the MEA does not rise in accordance with life expectancy, people will pay taxes for a shorter portion of their lives and collect Medicare benefits for a longer portion. This leads to unsustainable program costs; as the CBO report finds, “the aging of the population…accounts for about half of the growth in spending (relative to GDP) on Medicare and other major federal health care programs projected for the next 25 years.”

If the MEA were raised, in the future people would be affected in various ways. According to the CBO report:

Of the 5.4 million people who would be affected by the higher MEA in 2021, about 5 percent would become uninsured, and approximately half of the group would obtain insurance from their or their spouses’ employers or former employers. The remainder (about 2.3 million people in 2021) would, in roughly equal parts, receive coverage through Medicaid, receive coverage through Medicare because they would qualify for DI benefits, or purchase insurance either through the health insurance exchanges that will become available in 2014 under the terms of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act…or in the non-group market.

The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget indicates that such a move would not only reduce taxpayer costs, but also reduce health costs for most seniors. While increasing the eligibility ages for Medicare and Social Security is a good step forward, it should be advanced as part of a package of reforms needed to put these programs on sound financial footing. The Heritage Foundation’s Saving the American Dream plan includes eligibility age increases as part of its proposals to transform Medicare and Social Security. In concert with other structural reforms, this plan would ensure that future generations in need of program benefits can count on them. Entitlement reform can be done, and Congress should not delay in communicating that to the American people.