4 Problems With Left’s Hypocritical Plan to Give Wealthy Constituents a Bigger SALT Deduction

Preston Brashers /

Liberal legislators in high-tax states like New York, New Jersey, and California seem determined to make sure that their own high-income constituents pay for as little of their big spending plan as possible.

Recently, the House of Representatives passed the largest expansion of means-tested welfare spending in U.S. history, along with hundreds of billions of new corporate welfare. In addition to about $2 trillion of new taxes in the bill, fully funding the so-called Build Back Better Act would require multitrillion-dollar tax increases in the future.

Members of congress in high-tax states boast that they fought to include an increase in the cap on state and local tax—commonly known as SALT—deductions, a provision that benefits high-income residents of their states. This change would effectively shift federal tax burdens away from the wealthy, especially those in high-tax states.

Since the 2017 passage of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, taxpayers that itemize their tax returns are limited to $10,000 of state and local tax deductions when determining their federal taxable income. Taxpayers can deduct state and local income taxes and property taxes (or sales tax in lieu of an income tax).

Under the House plan, the cap on SALT deductions would increase to $80,000 through 2030. This is problematic for several reasons.

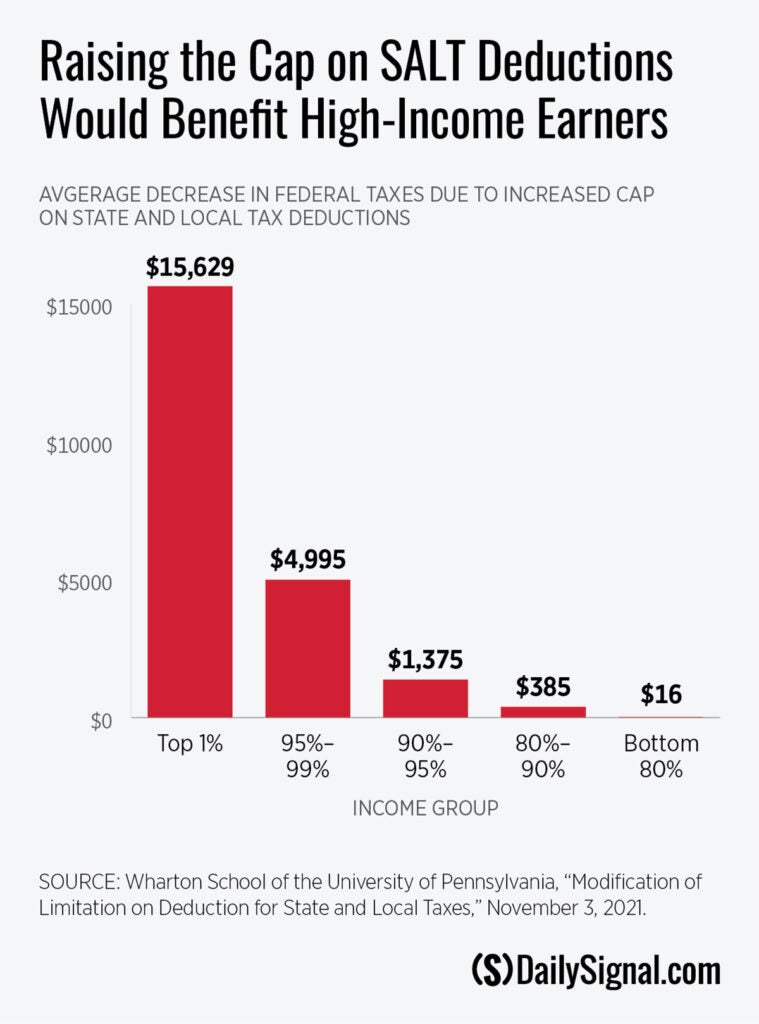

Problem #1: Taxpayers in the Top 1% Would Benefit From This Provision Nearly 1,000 Times More Than Taxpayers in the Bottom 80%.

Cutting taxes on the wealthy is not necessarily problematic. After all, the wealthy do pay an inordinate share of federal taxes. However, a large tax cut benefiting the wealthy is certainly noteworthy, given President Joe Biden’s false claim that households earning less than $400,000 a year wouldn’t “pay a penny more” under his plan, and his vow to make the highest income Americans “pay their fair share.”

Yet, according to the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, raising the SALT deduction cap—a benefit almost exclusively for the wealthy—is the single most expensive provision in the bill. The organization estimates that increasing the SALT deduction cap would reduce revenues by $275 billion through 2025.

Because of the increased SALT cap, taxpayers making $500,000 to $1,000,000 would receive an overall tax cut under the bill of 1.8% in 2023 and 2.5% in 2025. Meanwhile, government scorekeepers estimate that taxpayers earning between $50,000 and $75,000 would face overall tax increases of 0.4% in 2023 and 0.3% in 2025.

The Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania estimates the increased SALT cap would reduce the federal taxes of the bottom 80% of taxpayers by about $16 in 2022. It would, on average, provide taxpayers in the top 1% a tax cut of nearly $16,000.

Fewer than 2% of taxpayers in the bottom 80% would benefit at all from a higher SALT deduction, partly because only about 6% of them itemize their deductions (due to the standard deduction having been doubled in 2017). Even among lower- and middle-income taxpayers that do itemize, they seldom pay $10,000 in state and local taxes, let alone the new $80,000 SALT limitation.

Problem #2: Proponents Rely on Deceptive Logical Arguments to Defend Raising the SALT Cap

Defending an expanded SALT deduction, Rep. Katie Porter, D-Calif., stated, “If you are forced to pay part of your income to the state where you live, you don’t have that income left over … The federal government ought to tax you on what you have left [after state taxes.]”

On the surface, that argument may make sense. But it ignores the benefit that taxpayers receive from the state and local government spending that their tax dollars fund. In a well-run state, residents should receive a net benefit from each dollar taxed and spent by the state government.

Voters either directly or indirectly (through elected representatives) choose the level of taxes and spending in their states and localities. Nobody is “forcing” taxpayers in California to pay higher state taxes, except California voters and California elected officials. The mere fact that residents of some states consume more goods and services provided by the public sector rather than by the private sector shouldn’t entitle those taxpayers to reductions in their federal taxes.

There’s a glaring logical inconsistency in arguing that the SALT deduction is necessary to level the playing field between taxpayers in big government states and small government states, while simultaneously voting for what could end up being the largest expansion of government spending in history.

Problem #3: The SALT Deduction Encourages Wasteful Spending by State and Local Governments.

The SALT deduction effectively acts as a federal subsidy of state and local government spending. The deduction insulates governments from negative consequences when they spend taxpayer dollars inefficiently, thereby encouraging more waste.

Suppose a taxpayer faces a 40% federal income tax rate. If his state taxes increase by $250, and he claims that $250 as a SALT deduction, he can then reduce his federal taxes by $100. Given the federal tax savings, the taxpayer may support a state government project that he values at $150 but costs him $250 in state taxes.

Let that sink in. With an unlimited federal SALT deduction subsidy, some high-income taxpayers could rationally shrug off projects with a 67% cost overrun ($100 divided by $150), because so much cost is absorbed by the federal government. The SALT deduction rewards wasteful spending and excessive taxation.

With or without the full SALT deduction subsidy, governments in many high-tax states have been poor stewards of taxpayer dollars, and residents of those states have fled to other states.

The four states whose residents benefit most from the SALT deduction (as a percentage of adjusted gross income) are New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and California. Every year, these high-tax states experience a large net outflow of residents moving to other states. In the year from 2015 to 2016, over 140,000 more tax filers moved out of these states than moved into them.

The migration out of these four states continues apace today. Between 2017 and 2019, New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and California lost almost 170,000 tax filers per year.

New York, New Jersey, Connecticut, and California have top individual income tax rates that range from 6.99% to 13.3%, compared to a U.S. average of about 5.3%. Property taxes in these four states are also very high. These four high-tax states rank 43rd, 47th, 49th, and 50th in net interstate migration. By contrast, of the seven states with no income tax (including investment income), four rank in the top seven for net interstate migration.

If migration is any indication, even with federal subsidization, many taxpayers in big government states were unhappy with their states’ burdensome taxes. It’s bad enough that taxpayers in New York and California must pay for their own government’s mismanagement, but taxpayers in other states absolutely shouldn’t have to share the tab.

Problem #4: Congress Shouldn’t Use the Tax Code to Promote One Style of State Government Over Others.

Changing federal tax law for the sole purpose of shifting the geographic burden of taxes is a perversion of our federalist system.

In 1932, liberal Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis wrote, “It is one of the happy incidents of the federal system that a single courageous state may, if its citizens choose, serve as a laboratory; and try novel social and economic experiments without risk to the rest of the country.”

While most on the right bristle at being guinea pigs in state governments’ social and economic experiments, most people—left or right—should see the value of a federal system where citizens can choose between 50 different state democracies.

A federalist system gives citizens more control over how they’re governed. If they disapprove of how their state or locality is run, Americans can move. Some Americans prefer expansive state and local government and are willing to pay the corresponding high taxes. Others prefer more limited state governments. Citizens’ ability to vote with their feet provides a natural check on poor state governance.

By shifting costs of state government away from the states, the SALT deduction weakens our federalist system. It tampers with the scales in the “laboratories of democracy,” biasing the system in favor of big state government.

It also biases the system toward certain forms of taxation over others, specifically encouraging income taxes over sales taxes. In 2017, of the seven states with no income tax, each ranked between 40th and 50th in SALT deductions (even otherwise high-tax Washington state).

Taxes on income are more economically damaging than sales taxes. Unlike sales taxes, income taxes discourage work, saving, and investing. Yet, the SALT deduction rewards states that choose an income tax over a sales tax.

The Senate Should Reject This Effort to Centralize Control Over Individuals and State Governments

Increasing the SALT deduction cap would add insult to injury for supporters of limited government. The rest of the Build Back Better Act would expand the role of the federal government in virtually every area of American life. A higher SALT deduction would encourage one-size-fits-all big government at the state level, too.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email [email protected] and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the URL or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.