‘Minneapolis Effect’ Caused Last Year’s Spike in Violent Crime

Alexander Phipps /

The spike in violent crime last year was a serious departure from recent crime patterns over the last several decades. In fact, 2020 was likely the deadliest year for gun-related homicides since 1999.

According to the Gun Violence Archive, more than 19,000 people died of gun violence in 2020. This spike was particularly acute in major cities across the country.

For example, Minneapolis saw a 95% year-over-year increase in homicides between May and Aug. 1. In Chicago, homicides more than doubled in July 2020, compared to 2019. And New York experienced a 50% increase in homicides and a 112% increase in shootings. Sadly, that is only the tip of the iceberg of cities that experienced this surge.

What caused that sudden spike? Paul Cassell, a law professor at the University of Utah and a former federal judge, persuasively answers that question in a recent law review article.

While many theories have been offered, including seasonal impacts, COVID-19 lockdown measures, and an increase in firearm purchases, Cassell finds that they do not adequately explain key facts about the nature of the spike of violent crime last year. A good theory, he says, should be able to explain the following key facts.

- The inordinate increase in homicides and other shooting crimes.

- The fact that other “street” or “blue collar” crimes remained relatively the same while shootings spiked.

- The timing of the violent surge, which began the last week of May, just days after the death of George Floyd.

- The fact that the violent crime spike was largely confined to major cities.

The theory that the summer weather was at least partially to blame for this jump in violence cannot explain the abnormal increase in violence. While it is generally true that warmer weather correlates with an increase in crime, the rate at which the violence increased last year is much higher than ordinary seasonal changes from previous years.

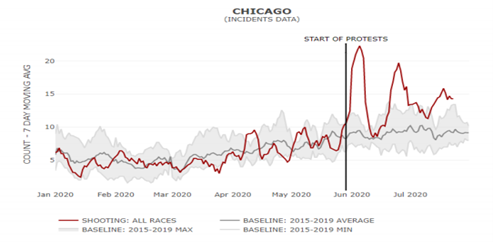

The following chart from Cassell’s paper lucidly demonstrates this point. While only focused on one city, the steep increase last summer displayed in the chart is characteristic of numerous major cities around the country.

The theory that the stay-at-home orders and business closures caused the spike fails to explain the timing of this phenomenon.

Multiple reports have found that the average homicide rate in cities decreased in April and May before the George Floyd protests began. If the lockdown measures alone caused this spike, the increase in homicides should have begun in March, when these shutdowns were first imposed.

Moreover, if the lockdown measures did cause this increase, why did the rate of other street crimes not increase as well?

Some may be tempted to suspect that the participants of the protests were the culprits of this violent spike. While there certainly was some violence directly connected to a few demonstrations, a majority of homicides occurred in low-income neighborhoods distant from the protests or riots.

Some theorize that the precipitous increase in firearm purchases explains the violent surge. Indeed, the increase in gun sales last year was tremendous. One report found about 2,109,000 “excess purchases” of firearms made between March and May. Yet these purchase patterns fail to explain the increase in violent crime for three reasons.

First, most guns were bought in March, at the outset of the pandemic, yet the increase in violence did not begin until three months later.

Second, if the thesis that “more guns equals more violence” were true, one would expect to see violent crime rise everywhere, since firearms were purchased across the country. But this was not the case. The increase in violent crimes manifested only in major cities.

Third, because there were already many privately owned firearms prior to the pandemic, the share of guns purchased during this sale spike amounts to only about 0.5% of all privately owned firearms in America. This tiny fraction of newly owned guns seems highly unlikely to be the cause of the significant increase in homicides.

By contrast, a theory called the “Minneapolis Effect” best explains the 2020 spike in gun-related violence. According to that theory, a reduction of proactive policing (also called depolicing)—such as street patrols, “stop, question, and frisks,” and traffic stops—resulted in an abrupt increase in homicides, at a rate akin to the levels of last summer.

Police pulled back from discretionary law enforcement activities primarily for two reasons. First, many officers were required to deal with the massive street demonstrations following the death of Floyd, taking them away from policing other areas of the city.

Second, officers responded to the social and political criticism of some of their proactive practices by cutting back on some of them.

Cassell cites a litany of studies that suggest proactive policing directly reduces gun crimes. He also points to evidence that indicates depolicing occurred in major cities after the anti-police protests began, such as the large number of officers quitting or temporarily leaving their jobs, eyewitness accounts of a smaller police presence, and a reduction of traffic stops.

Cassell cites a compelling, data-driven Minneapolis Star-Tribune article that stated that from June through August “nearly every other metric of police activity fell sharply compared to last year, and across every precinct” in Minneapolis.

Cassell’s theory also explains the four key facts outlined above. As to the first—a precipitous spike in firearm-related homicides—other examples show how depolicing causes an increase in shootings.

In 2016, homicides in Chicago increased by 58% after “stop, question, and frisks” were reduced by the Chicago Police Department beginning in December 2015.

Regarding the second, studies suggest that proactive policing does not reduce other street crimes, such as petty theft, which would explain why there was an uptick in shootings, but not other crimes, following the depolicing phenomenon last year.

Regarding the third, the Minneapolis Effect also explains the timing of the increase in shootings, because depolicing did not occur until the anti-police protests began late in May.

And regarding the fourth, the Minneapolis Effect also unravels the mystery of the geographic concentration of frequent shootings. Anti-police protests were predominately in urban areas that witnessed depolicing, whereas rural areas did not experience the same number of protests, leaving policing patterns relatively stable along with rates of shootings.

Understanding the cause of last year’s surge in violence is particularly important for saving lives in the future, especially in disadvantaged communities as the overwhelming loss of lives from last year’s shootings occurred in black and brown communities.

For instance, in Chicago, 94% of the homicide victims were black or Latino; in Philadelphia, 81% were black men or boys; and in New York City, 90% were black or brown. Protecting black and brown lives, therefore, will require major cities to rethink how they use officers during troubling times.

The Federalist Society originally published this article.

Have an opinion about this article? To sound off, please email letters@DailySignal.com and we’ll consider publishing your edited remarks in our regular “We Hear You” feature. Remember to include the URL or headline of the article plus your name and town and/or state.