When It Comes to COVID-19 Deaths, Florida Is No ‘New York’

Doug Badger /

“I just want to make it clear to the American public,” proclaimed Dr. Deborah Birx, White House coronavirus task force head, on July 24, “What we have right now are essentially three New Yorks, with these three major states.”

The three states in question—Florida, Texas, and California—all have seen sharp increases in COVID-19 infections in recent weeks.

But when it comes to COVID-19-related deaths, there’s only one New York, as this chart shows. It makes it clear that Florida’s coronavirus deaths per million residents is nowhere near as bad as New York’s.

Despite rising cases and deaths, Florida’s COVID-19 mortalities per million residents remain below the national average, according to data accessed on July 27 from Worldometer. It is well below death rates in New York City, New York state (including New York City), New Jersey (whose counties with the most deaths are New York City suburbs), Connecticut (which similarly experienced large numbers of cases in suburban New York City counties), and Massachusetts.

For Florida’s COVID-19 mortality rate to reach that of New York City, deaths would have to rise from its current level of just over 6,000 to more than 83,000. To match New Jersey’s death rate would require total Florida deaths to eclipse 38,000.

That’s not outside the realm of possibility, of course, but seems improbable.

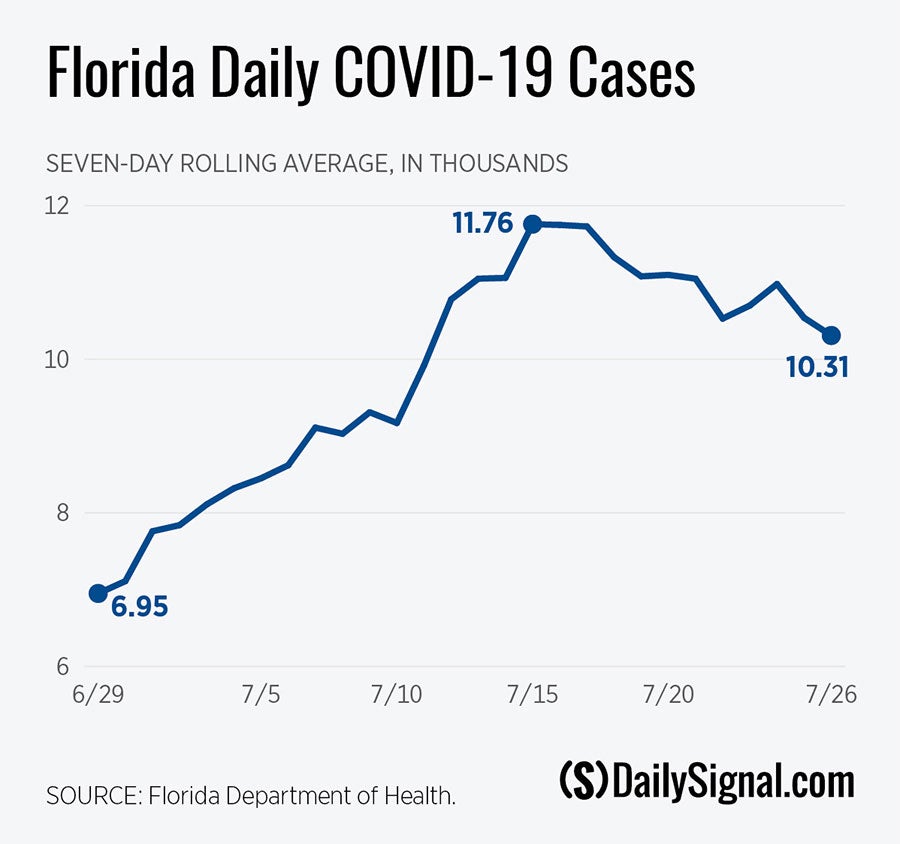

And while Florida has seen its new infections climb throughout most of June and July, fresh data from the Florida Department of Health suggest that the rising tide of COVID-19 cases may have crested.

Here is a seven-day moving average of cases from June 29 through July 26, during which infections reached record rates.

The chart shows the average daily count of cases over a rolling seven-day period. The June 29 figure, for example, represents the average number of new cases reported between June 23 and June 29, while the June 30 average is for cases reported between June 24 and June 30, and so on.

That average rose from just under 7,000 cases on June 29 to a peak of nearly 12,000 during mid-July. But in recent days, the pace appears to have subsided, registering an average of 10,308 cases on July 26.

While that is encouraging, caution is in order. The pandemic has traced an uncertain course that has confounded predictive models. And while the apparent plateauing of new cases may be a signal that rates have begun to decline, the number of new infections remains elevated and portends more hospitalizations and deaths during August.

Although Florida is no New York when it comes to COVID-19-related mortalities, its death count is trending upwards. Total coronavirus deaths in the state exceed 6,000, with more than 2,500 of them occurring over the first four weeks of July.

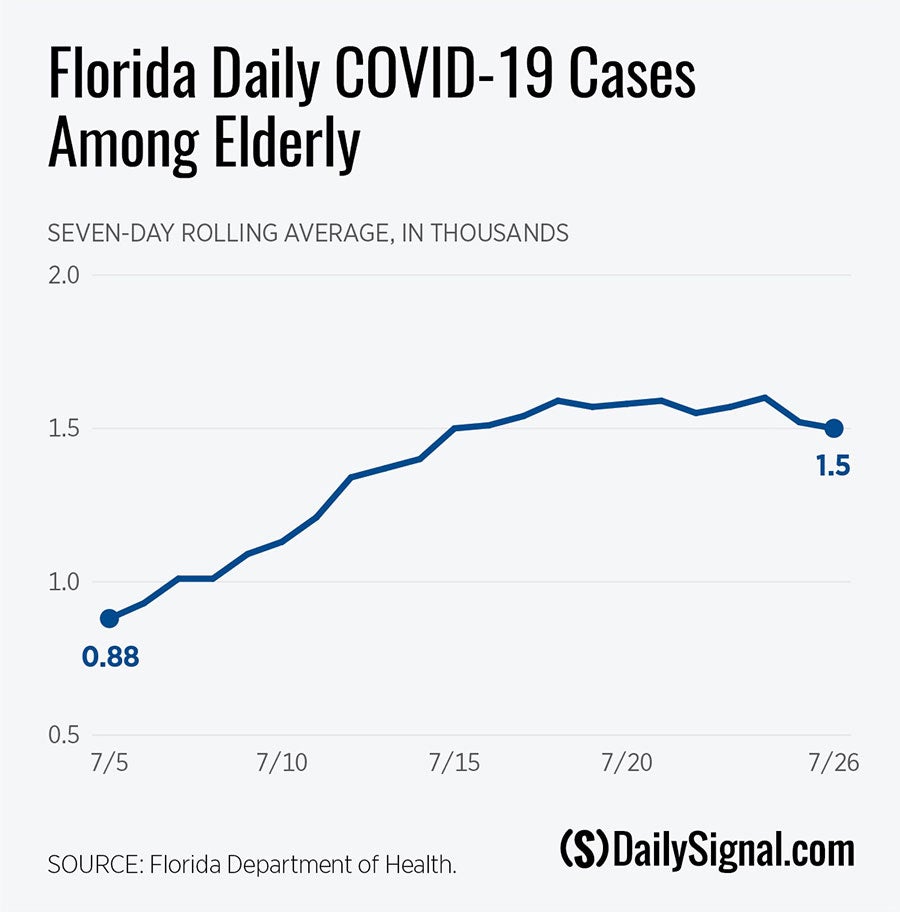

That unfortunate trend will likely accelerate during August, since the number of newly infected seniors has risen significantly. Here is a chart showing the seven-day moving average of new cases among the elderly between July 5 and July 26.

In my previous Florida update, I observed that seniors made up a smaller percentageof new cases, but noted that it was a smaller percentage of a larger number. The chart above shows that those numbers have increased. The seven-day averageof daily new cases among Florida’s elderly has risen from fewer than 900 on July 5 to nearly 1,600 on July 18 and still remains elevated.

That is an ominous sign. A recent study found that COVID-19 mortality rates are near zero for children and younger adults but climb exponentially with age, reaching 24% for people over 80. Florida’s experience confirms those estimates. Seniors account for 82% of the state’s COVID-19 deaths.

The tragically inevitable consequence of more new cases among seniors in July is more deaths in August.

State leaders recognize this trend and are working to reverse it. They have adopted a measured approach to the contagion, in part because they have learned from New York’s errors, in part because front-line medical workers have discovered more effective ways to treat the illness, and in part because they have developed a strategy driven more by data than by fear.

That approach, which has focused on protecting those in nursing homes and helping the state’s hospitals accommodate a surge in patients, also places trust in the good sense of its residents, businesses, and churches to practice appropriate behaviors.

That reliance on common sense can be misplaced, as the rise in cases among the elderly shows. Seniors who ignore warnings from Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis and other officials to avoid crowds, closed spaces, and close contact are endangering themselves.

The state’s response to the pandemic can improve. It needs to do a much better job, for example, of delivering prompt test results, a problem that has emerged nationally, and one that Birx and her team have bungled from the pandemic’s onset.

Their energies too often are channeled toward apocalyptic pronouncements that have generally proven as errant as the ceremonial first pitch Dr. Anthony Fauci threw on baseball’s opening day.

A fitting metaphor for a public health establishment that can’t seem to get it right.