Supreme Court Hands Huge Victory to Families on School Choice

Lindsey Burke / Emilie Kao /

In a 5-4 decision Tuesday, the Supreme Court held that families have a right to seek the best educational opportunities for their children, by preventing states from blocking the participation of religiously affiliated schools in state school choice programs.

In Espinoza v. Montana Department of Revenue, the court ruled that the application of a “no-aid” provision in Montana’s Constitution violated the Free Exercise Clause of the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, since it barred state tax credit scholarships from being used at private religious schools.

In a huge win for families, the high court held that states cannot apply the no-aid provision to discriminate against religious schools by excluding them from private school choice programs.

In 2002, the court’s ruling in Zelman v. Simmons-Harris held that the Establishment Clause of the U.S. Constitution did not block parents from choosing schools that are the best fit for their children, including religious schools.

Tuesday’s decision in Espinoza removed the largest state constitutional obstacle by holding that so-called Blaine Amendments cannot be used to deny choice to parents.

Under the U.S. Constitution, states no longer may prevent parents from choosing religious schools if they are participating in a school choice program.

“A state need not subsidize private education. But once a State decides to do so, it cannot disqualify some private schools simply because they are religious,” Chief Justice John Roberts wrote in the opinion of the court in Espinoza.

This decision struck a blow to the notoriously anti-Catholic Blaine Amendment in Montana’s Constitution that sanctioned explicit discrimination against religious schools in funding. Montana’s discrimination hurt families who have a wide variety of values and preferences when it comes to their children’s education.

As the Supreme Court had previously noted, Blaine Amendments have an “ignoble” history. The amendments are named after Sen. James G. Blaine of Maine, who in 1875 sought a federal constitutional prohibition of aid to “sectarian” schools.

“Consideration of the amendment arose at a time of pervasive hostility to the Catholic Church and to Catholics in general, and it was an open secret that sectarian was code for Catholic,” Justice Clarence Thomas wrote in the court’s Mitchell v. Helms decision in 2000.

As Jarrett Stepman and one of us, Lindsey Burke, wrote previously in the Journal of School Choice:

Catholics sought to establish their own schools, and proposed that funding should follow, as it had to the common school (proto-public schools).

Supporters of the common school movement perceived a threat to its mission in such proposals. … Against this backdrop, Blaine [Amendments] sought to prevent aid to Catholic schooling as part of a wider reaction to increased Catholic immigration.

Blaine’s effort to amend the U.S. Constitution failed in 1875, but his effort still served as a major impediment to school choice, continuing to thwart modern-day school choice programs in the 21st century.

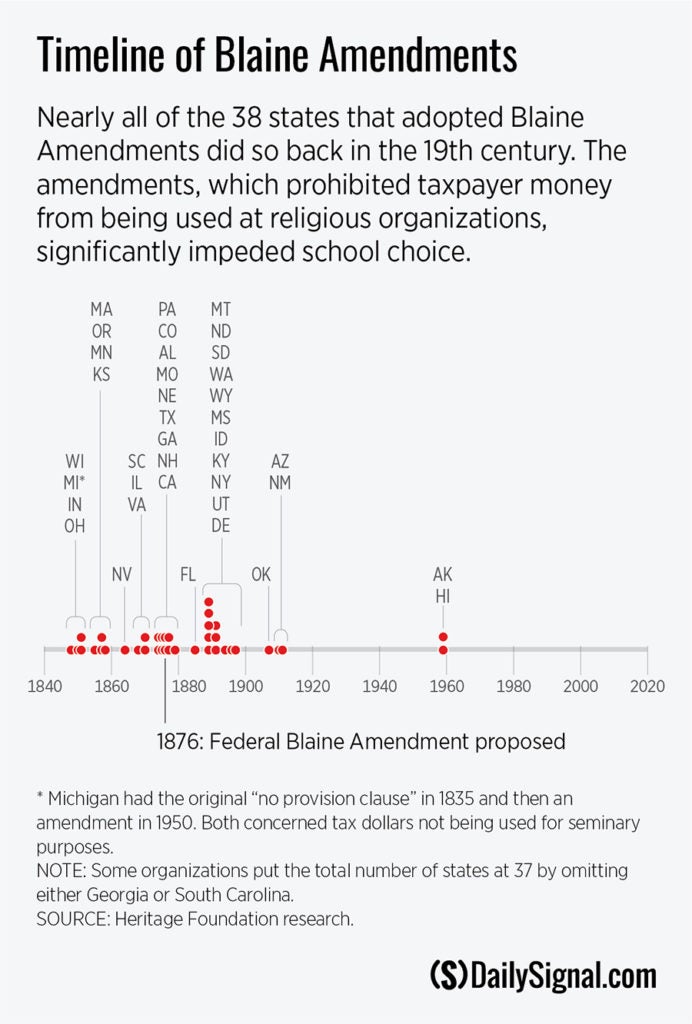

That’s because 37 states went on to adopt similar amendments, sometimes referred to as “baby Blaine Amendments.” Prior to today’s ruling, in states such as Montana, many of these state Blaine Amendments and similar “compelled support” clauses restricted or outright prohibited the use of taxpayer funds at private religious schools.

This timeline shows when states adopted Blaine Amendments and similar “compelled support” clauses.

The Supreme Court made it clear Tuesday that the Free Exercise Clause of the Constitution prohibits discrimination against religious schools on the basis of their religious status—a status that provides families with more education options that best meet the needs of their children.

The high court said that if states create a publicly available benefit, such as a scholarship program, they must allow religious schools to participate. The states that have Blaine Amendments in place are now prohibited from excluding religious school options.

In Mitchell v. Helms, Thomas wrote of Blaine Amendments: “This doctrine, born of bigotry, should be buried now.” On Tuesday, the Supreme Court’s decision in Espinoza took us one step closer to achieving that goal.

Now is the time for states to cast aside these 19th-century rules rooted in prejudice that unfairly punish religious families, students, and schools. The Constitution requires states to provide a level playing field for religious and secular education.

The legal impediment to school choice programs is now gone, and it’s up to state legislatures to move forward advancing education choice.

The court made it clear that policymakers across the country now have the power to enact robust school choice programs. They should do just that.