As Unemployment Keeps Rising, Congress Needs to Fix What It Broke

Rachel Greszler /

Another 2.4 million workers filed for unemployment claims last week, bringing the 10-week total to nearly 39 million. If all of these represent separate claims, that means that almost 1 in 4 workers has filed for unemployment since the coronavirus shutdowns began.

That’s bad news because unemployment is undesirable at best, and devastating at worst.

The situation has both short-term and long-term consequences for unemployed individuals, and really, it’s to no one’s advantage. At least not normally.

But now, because of Congress’ problematic additional unemployment benefit of $600, unemployment has become advantageous—even preferable—to some workers, employers, and state and local governments.

>>> When can America reopen? The National Coronavirus Recovery Commission, a project of The Heritage Foundation, is gathering America’s top thinkers together to figure that out. Learn more here.

Instead of simply providing workers with a higher percentage of their usual earnings than the roughly 40% to 50% that state unemployment systems normally provide—which was appropriate and had bipartisan support—Congress messed up by giving everyone the same additional $600 per week, regardless of whether they had been making $100 a week or $1,000 a week.

Now, the majority of unemployed workers are receiving higher unemployment benefits than their usual paychecks.

A JPMorgan Chase analysis estimated that between 65% and 75% of workers are receiving more from unemployment than their paychecks. And an analysis by professors at the University of Chicago estimated that the median unemployment benefit equals 134% of workers’ previous wages, while 1 in 5 workers is receiving 200% or more of previous earnings and 1 in 10 is receiving almost 300% of previous earnings.

That’s both inequitable and counterproductive to the economic recovery.

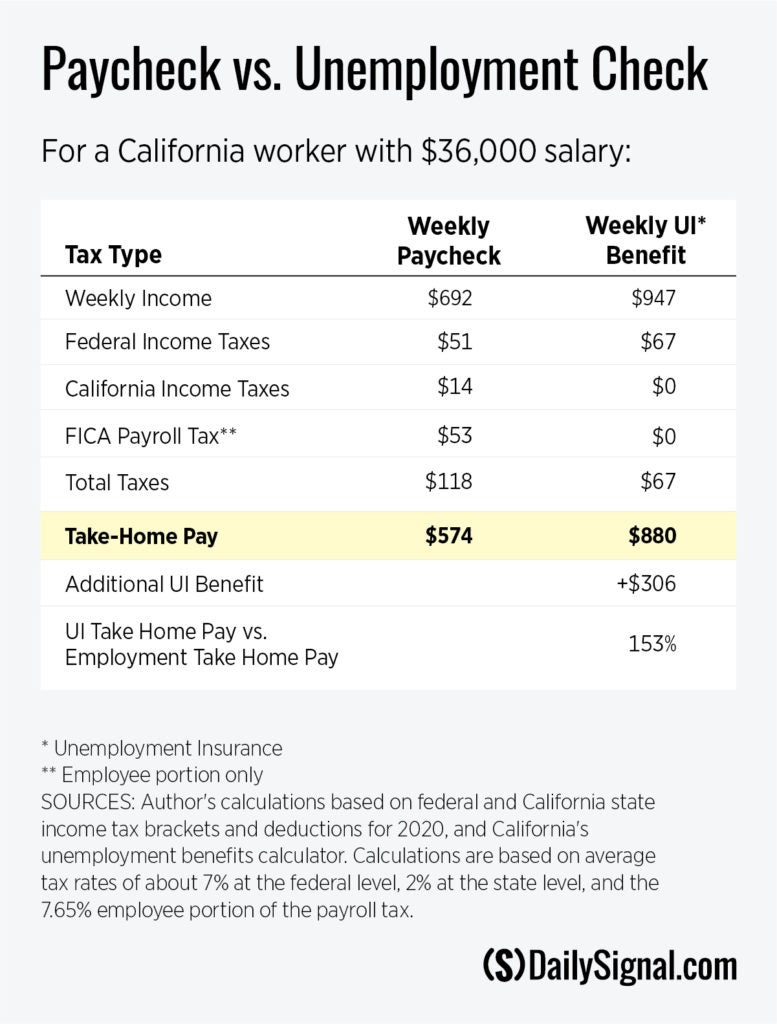

As the table below shows, someone in California who makes $36,000 per year—perhaps a nursing home or construction worker—would receive 53% more, or an extra $306 per week—by being unemployed as opposed to employed. (Note that individuals do not have to pay payroll taxes on unemployment benefits and a few states—including California—do not tax unemployment benefits.)

That’s hardly fair for the hardworking Americans who have continued to do their jobs each day.

And it’s not fair to unemployed workers to increase their risks of long-term unemployment.

In light of the unprecedented circumstances, it was appropriate for policymakers to temporarily increase unemployment benefits, but wrong for them to make unemployment pay more than employment.

Some policymakers who want to extend the expanded unemployment benefits until January or March of 2021 argue that it would be heartless to cut off bonus unemployment benefits on July 31.

But enticing workers with an extra $31,200 in unemployment benefits (potentially over $50,000 in total unemployment benefits) if they remain unemployed for a year could be far more damaging—both to individuals and to society.

Long-term unemployment results in lower incomes and fewer opportunities, as well as detrimental impacts on physical and emotional well-being.

Moreover, if Congress doesn’t fix this problem (by capping unemployment benefits at no more than 100% of workers’ wages) and instead extends excessive benefits, shortages of willing workers will contribute to more failures of small businesses.

Examples from around the country show that many small businesses are ready to open back up, but some workers don’t want to come back until their bonus $600 benefits expire.

Some lawmakers have suggested that those employers should just pay their workers more and raise their prices to cover the higher labor costs. But most small businesses are struggling just to stay afloat and wouldn’t be able to survive if they significantly increase prices. Those business failures would hurt both workers and their customers.

Take day care facilities, for example. Many parents will not be able to go back to work until day care centers reopen, but if providers raise prices enough to pay child care workers more than they are making on unemployment, families wouldn’t be able to afford child care.

Although larger businesses may be able to hang on in the short term, some likely will eliminate positions—disproportionately lower-skilled ones—to remain viable. That will exacerbate unemployment and leave workers with even fewer options.

And finally, while a massive public health pandemic such as COVID-19 warrants a federal government response, such measures must be targeted and directly aimed at combating the pandemic and enabling an economic recovery.

That’s not the case with the $600 benefit, which invites misuse and abuse. In some cases, it’s also unfairly redistributing and driving up costs.

In Portland, Oregon, for example, the school district and teachers union teamed up to devise a strategy—Friday furloughs—that will allow teachers to work less and earn more.

Instead of the usual $460 in daily district pay supported by Oregon taxpayers, Friday-furloughed teachers would receive an average $730 in unemployment benefits supported by federal taxpayers.

These excessive unemployment benefits hurt the nation’s recovery. And at an estimated cost of $279 billion through July alone—equal to $2,170 for every household in the United States—the House’s proposal to extend the benefit into 2021 would shift even greater costs onto ordinary Americans.

Americans are hard-wired for work. Beyond a paycheck, producing goods and services of value and interacting with others are fundamental to human flourishing.

Tens of millions of workers have lost their jobs through no fault of their own and most of them want to get back to work as soon as it’s safe to do so.

It’s time for Congress to focus on creating an environment that fosters employment opportunities instead of unemployment incentives.

This commentary has been modified since publication to specify the effect on larger businesses of the $600 extra unemployment benefit. The article and accompanying chart also were corrected July 7 to note that the benefit gives a typical California worker $306 more per week than his usual paycheck, a slightly higher amount than previously stated here.