‘Flattening the Curve’ Critical to Fighting Coronavirus

Peter Brookes /

Some commentators have ominously suggested that the United States is just a few days—maybe a week to 10 days—behind the crippling coronavirus crisis that is hammering Europe, especially Italy.

If true, that’s troubling.

That said, however, taking personal responsibility for doing the right thing with public hygiene and the new (to most of us) concept of social distancing to flatten the possible infection curve could mean the difference between success and failure in fighting the virus here in this country.

Simple as it seems, social distancing and public hygiene practices could end up being a matter of life and death.

As we all are painfully aware, Italy is in the middle of an epic biological battle with the coronavirus and the resulting disease, COVID-19.

In Italy, the virus has infected almost 28,000 and tragically taken the lives of nearly 2,200. Last week, nearly 370 died in one day in Italy from COVID-19—a tragic new record for that nation.

Italy has the most cases of any country outside China, which itself suffered some 80,000 infected and 3,000 dead since the virus started spreading in the city of Wuhan in central China in November.

In early March, the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus outbreak a pandemic. Today, it has spread across the globe, infecting some 180,000 people in more than 150 countries.

In the United States, cases were confirmed in every state, now including West Virginia, which reported its first case Tuesday.

Due to the spread of the virus, the Trump administration has moved from a strict strategy of containment to one of containment and mitigation.

Social distancing, respiratory etiquette (e.g., covering a cough or a sneeze), and hand-washing are really just common sense. But it isn’t merely about reducing your chances of contracting the virus.

By minimizing the potential contact between uninfected people and disease carriers, public health officials hope to slow the spread of the outbreak, easing stress on our health care system, and reducing cases among at-risk groups.

Per the World Health Organization, 80% of those who contract coronavirus will display only mild symptoms. And yet, not only is the virus potentially more infectious than the flu, COVID-19 also may be comparatively more deadly, especially for the elderly.

The other concern is that the virus may “shed”—that is, spread—from people who are without any symptoms (i.e., asymptomatic), as well as from those who display classic flu-like symptoms (e.g., fever and cough) that often accompany the virus.

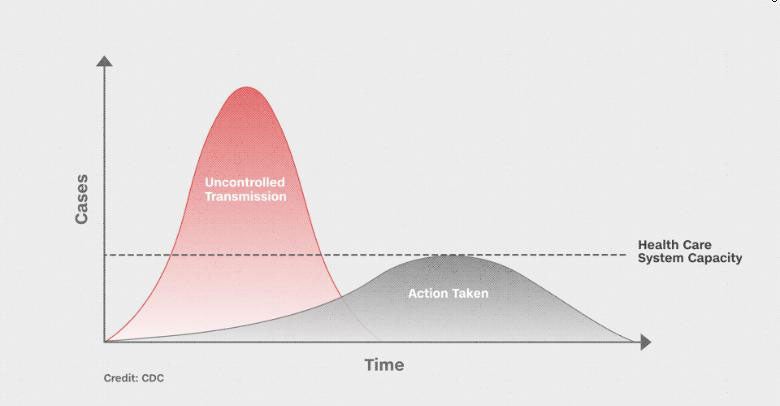

Implementing social distancing is critical to the public health concept of “flattening the curve.” The point of putting some distance between yourself and others is to reduce the possible spike in number of people infected with coronavirus.

Reducing a rapid spike in the number of infected people needing medical attention—such as has been seen in Italy—would reduce the chances of overwhelming the U.S. health care system just coming off the likely peak of a tough flu season.

During a viral outbreak of this scale, there is likely to be an increased need for personal protective equipment (surgical masks, gloves, etc.), hospital and intensive-care beds, pharmaceuticals, and ventilators for those in respiratory distress.

More critical to our success than medical materiel is preventing the virus from overpowering our force of intrepid health care professionals with immense caseloads, overwork, exhaustion, and potential exposure to the disease.

Even with the world’s best health security, America’s available medical resources in materiel and personnel are, like every other country in the world, finite.

Social distancing, along with good public hygiene practices, could lead to a lowering of the infection curve. This means that, even as we ramp up our health care capacity for the coronavirus pandemic, we may be able to stay within the capacity limits of our health care system.