3 Steps to Take the Surprise Out of Surprise Medical Bills

Doug Badger /

Surprise medical bills are a source of frustration for many Americans. Patients who schedule medical care from network physicians or at network hospitals sometimes receive bills from doctors outside the network such as anesthesiologists, radiologists, or pathologists.

Or a patient may be transported to a nearby emergency department, only to learn that the hospital was not in her insurance company’s network.

In cases like these, patients are saddled with bills that can be very high, potentially running into tens or even hundreds of thousands of dollars.

In a new paper, coauthor Brian Blase and I propose a market-based solution to such surprise medical bills. This proposal, if implemented, will equip consumers with the information they need to so they can make more informed health care decisions.

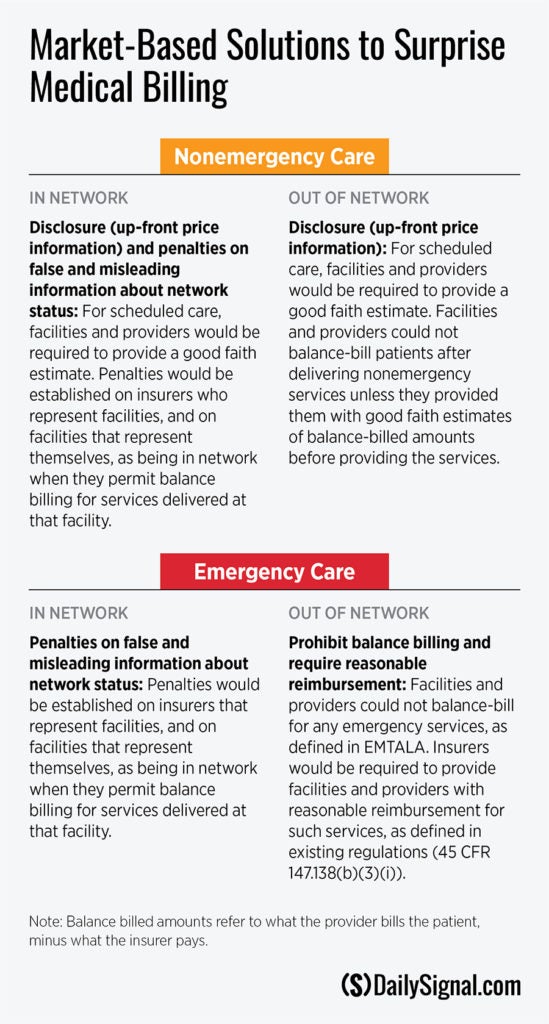

Our proposal requires insurers and providers to supply accurate and timely information about networks and prices. It segments the surprise billing problem into four distinct categories, depending on the network status of the facility and whether the medical services are emergency or nonemergency.

Here are the three major elements of our recommendations:

1. Price disclosure. Unlike virtually every other service in the economy, consumers don’t know the prices of scheduled, nonemergency care until long after receiving it. The government does not need to mandate price disclosure in other areas of the economy that function efficiently. But efficiency is not a key feature of health care markets, which are beset by excessive third-party payment and price opacity.

Congress should correct this problem by requiring providers to supply a good faith estimate of the cost of scheduled medical care before it occurs, unless the patient affirmatively declines an estimate. Providers that refuse to supply an estimate before providing care could not “balance bill” (i.e., charge a patient an amount above what the insurer pays the provider) afterward.

2. Penalties on insurers and providers for supplying false and misleading information about a facility’s network status. Consumers typically seek network physicians and hospitals to avoid high out-of-network bills. They rely on representations about network status from their insurance company and from the hospital itself.

What their insurer and hospital often don’t tell patients is that other doctors who might participate in their care are notpart of their insurer’s network. Patients learn that only weeks or months later, when the bill from the non-network physician arrives.

Congress should protect consumers against false and misleading information. It should establish penalties for insurers that represent a facility as being in-network, and a facility that presents itself as being in-network, if doctors balance-bill for services they provide at that facility.

To be considered a network facility, the insurer, the facility, and the doctors who practice there would have to negotiate arrangements that protect patients against surprise bills. Hospitals that permit surprise bills could not be represented as network hospitals without penalty.

3. Ban balance billing at non-network emergency departments. Accurate information about a hospital’s network status and price transparency don’t help the patient who is suffering severe chest pains or being transported in an ambulance. Such patients generally will go or be taken to the nearest emergency room. Broad consensus exists in Congress and among the public that patients in those circumstances should not face large bills for out-of-network care.

Consistent with that consensus, we propose that Congress ban surprise billing in these limited circumstances and require insurers to pay, and providers to accept, reimbursement rates spelled out in existing federal regulations.

Those regulations, which already govern insurance company payments to non-network providers of emergency care, require insurers to pay providers the greatest of: a) the Medicare rate; b) the median network rate; or c) the amount an insurer generally pays non-network providers.

The alternatives—such as doing nothing and arbitration—are worse, and accurate information about network status and prices are of no value in this unique circumstance.

These recommendations should, to the extent possible, be implemented in a way that preserves the ability of states to adopt policies that best serve their residents.

This proposal offers a better path for Congress, which currently seems headed in a very different and counterproductive direction. Although they differ in some respects, the House and Senate proposals rely on sweeping and unnecessary federal price regulation, rather than market-based alternatives, to eliminate balance billing. Both would force doctors and insurers who have not contracted with each other to accept rates set in contracts they haven’t signed.

The principal appeal of rate-setting is that the Congressional Budget Office believes it will produce budgetary savings–savings that Congress plans to spend to fund government programs. While budget savings are great, they should not drive Congress to impose rates outside government programs.

Our proposal guarantees no more surprises without resorting to heavy-handed measures. If consumers go to an in-network facility, they can’t be balance-billed. And they will receive good faith estimates for scheduled care.

Congress should solve the balance-billing problem by giving patients more control over their medical care with accurate information about medical prices.