In Military Affairs, Quantity Really Does Matter

Dakota Wood /

In a recent article, the staff at Stratfor Worldview noted how the unwillingness and/or inability of allies to work with the U.S. to address regional security concerns ultimately limits the ability of America to meet new challenges.

In early 2018, then-Secretary of Defense James Mattis made the case that a period of “long-term strategic competition” now existed with other major powers given the rise of China and the re-emergence of Russia during a time marked by “rapid technological change, challenges from adversaries in every operating domain, and the impact on current readiness from the longest continuous stretch of armed conflict in our [n]ation’s history.”

During the Cold War, the U.S. was chiefly engaged in strategic competition with the Soviet Union, aided by strong NATO allies, and was able to focus its efforts primarily in Europe. But the world has changed dramatically over the past quarter-century and the U.S. must now spread its resources globally, accounting for a broad range of competitors, but largely without the supporting strength of friends who have allowed their defense capabilities to wither.

In such a world, the capacity of the U.S. military to defend America’s interests matters a great deal.

“Capacity” is one of the key metrics we emphasize in The Heritage Foundation’s Index of U.S. Military Strength. Americans certainly want their military to have quality equipment and well-trained people, but a small force, even if well-trained and equipped, can only do so much and is easily spread too thin.

When a force that is small, relative to demands for its use, is routinely employed, recovering from employment, and getting ready to deploy again, it doesn’t have much ability to respond to changes in the national security environment and therefore limits options when new challenges do arise. The military services want to shift to the demands implied by a return to “great power competition,” and the investments being made by Russia, China, and others in more advanced capabilities. But it is hard to do so when the force is also covering such hot spots as the Korean peninsula, Syria, Iraq, Afghanistan, Iranian activity in the Gulf, western Africa, Somalia, the Baltic region, drug smuggling on both sides of Latin America, and exercises with various partners, among other things.

Obviously reducing our commitments abroad would free capacity, but at direct risk to America’s security, economic, and diplomatic interests in the affected regions.

If allies had more capacity, and the political will to use their forces to address mutual interests like the unhindered flow of oil and commerce in international waters, the U.S. would be better able to concentrate efforts. But they do not. Thus the U.S. often finds itself having to go it alone.

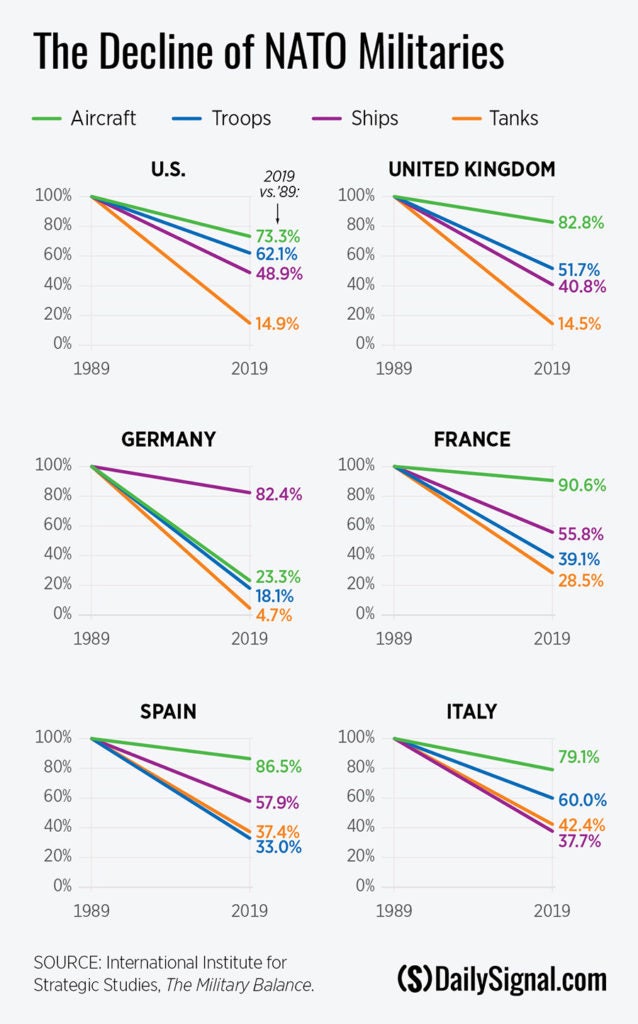

At the end of the Cold War, every major country made dramatic reductions in military capacity (the states shown in the graphic are just a few examples). For the vast majority of states, the reduction in capacity was surpassed by an even greater reduction in readiness. In many cases, even where a country maintains some number of troops, ships, or planes, the equipment doesn’t work and the people aren’t operationally competent.

There are consequences to sustained reductions in military capabilities that rapidly affect economic and diplomatic efforts. And it takes many years to rebuild military power. For the U.S., weak allies limit what it can do in many different locations. For allies who have staked their security on the U.S. “being there,” they are running the risk of the U.S. having higher priorities elsewhere.

It’s all about managing risk and most countries do it poorly.

Defense spending is only one measure of military power and not an entirely satisfactory one. For example, the U.K. has met the NATO target of 2% of GDP spent on defense, but was largely only able to make this mark by increasing spending on manpower. So, it has better paid troops, but no increase in their number and certainly no increase in the primary equipment a military needs to do anything.

In fact, the British military has continued to shrink and the government has been considering even greater cuts in order to shift defense money to domestic programs, at least until we see what newly installed Prime Minister Boris Johnson has to say about it. In many ways, how money is spent is more important than how much money is spent, but one cannot ignore that total amount dedicated to a nation’s security (which includes economic) interests.

At present, U.S. spending on defense accounts for only 15.1% of federal spending and 3.2% of GDP (see p. 268 here). These are historically low numbers for America and reflect a major shift to ever-more federal spending on domestic entitlement programs. Ultimately, the size of the federal budget and how it is spent reflects what the American public writ large determines is important since budgets are approved by elected representatives in Congress.

But unseen by most Americans is the decline in the ability of our allies to assist, the increase in competitor capabilities as they invest in expanding and improving their militaries, and just how stretched the U.S. military has become to do all the things demanded of it.

Often lost in the partisan tug of war in Congress is that national defense is one of the few explicit constitutional responsibilities of the federal government. The public plays an important role in periodically reminding its representatives in Washington of this responsibility and the risks America runs if not adequately investing in its security relative to changing conditions in a dynamic world.

Losing focus on the critical, balanced triad of capability, capacity, and readiness results in a military that is unable to fulfill its role in keeping America safe, free, and prosperous. And this isn’t the responsibility of any ally; it rests solely on America itself.