After Defeat of ISIS, Iraq’s Christians and Yazidis Adjust to Uneasy Peace

Nolan Peterson /

ST. MATTHEW’S MONASTERY, Iraq—Some 20 miles from Mosul in northern Iraq’s Nineveh Plains, this Christian monastery has stood high on the slopes of Mount Alfaf since the year 363. Once home to about 7,000 monks in the ninth century, it’s among the oldest Christian monasteries in the world.

Over the centuries, St. Matthew’s Monastery has survived attacks by Kurds, Muslim tribes, and the Mongol emperor Tamerlane. Yet perhaps the direst threat of all came in 2014 when the Islamic State’s terrorist army rampaged across Syria and northern Iraq to take control of Mosul.

Bolstered by a U.S.-led bombing campaign, a force of Kurdish peshmerga fighters—who are Sunni Muslims—stopped the advancing Islamic State militants just 2.5 miles from the beige stone citadel of St. Matthew’s.

Today, Christians from Mosul and the surrounding villages make the trek up to the historic Syriac Orthodox monastery every Sunday to celebrate mass.

“It’s safe for us to pray here,” says Besman Naif, 42, a Christian man from the nearby village of Mergey at the foot of Mount Alfaf. “We aren’t safe anywhere else.”

A coalition of Kurdish and Iraqi forces liberated Mosul from the Islamic State (also known as ISIS) in 2017. Yet Naif, who is originally from Mosul, says he won’t return to the city anytime soon.

“The Daesh mentality is still there, many well-known terrorists just blended back into the community,” Naif says, using a pejorative Arabic nickname for ISIS. “There are still Daesh cells operating in the city. It’s very dangerous.”

Living on the Edge

The U.S. declared victory over the Islamic State in March after the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces overran the terrorist group’s final stronghold in the Syrian village of Baghuz.

As a territorial power, the caliphate is no more. Yet, the underground ISIS network of sleeper cells and sympathizers remains a lethal threat to Iraq’s religious minorities.

Across the country, Christians and Yazidis continue to live on edge, wary about publicly demonstrating their faiths for fear of violent reprisals. And for those who sought refuge from the Islamic State’s wrath by fleeing to safety in Iraqi Kurdistan, returning home to places such as Mosul or Sinjar remains a prohibitively frightening proposition.

“The threat from remaining ISIS members and followers remains. It is a big mistake to think that ISIS is completely defeated,” says Pari Ibrahim, founder and executive director of the Free Yezidi Foundation, a nonprofit that provides assistance to displaced Yazidis. (Yezidi is an alternate spelling for Yazidi.)

“There are many thousands of ISIS members and huge numbers of ISIS sympathizers and supporters throughout areas in Iraq and Syria,” Ibrahim tells The Daily Signal. “Even if the attacks become insurgent operations, we should remember that there are many towns and areas that believe in what ISIS said. That is an existential threat to Yezidis, especially, and to all civilians, and it will remain so.”

The bedrock, ideological catalysts that spawned the Islamic State—and drew many fighters from Iraq to join the terrorist army’s ranks—still exist within the region’s shadows, posing a perpetual, existential threat to Iraq’s religious minorities. The region, therefore, remains a fertile breeding ground for the Islamic State’s brand of militant Islamist extremism.

“The Islamic State was excessively brutal, but it did not come from a vacuum,” says Elizabeth Monier, a fellow in the Department of Middle Eastern Studies at the University of Cambridge.

“There is certainly lingering distrust. This is clear from the slow return of Christians to their homes in northern Iraq,” Monier says, adding:

The cause is not just fears that ISIS might return … ISIS is not an isolated threat. There is mistrust toward Muslim neighbors, some of whom were complicit in the violence and looting, and a lack of confidence in the commitment and ability of the central government to guarantee security of minorities.

Brink of Disaster

On a blazing hot day in late May, I stand on a rooftop terrace at St. Matthew’s Monastery and admire the view overlooking northern Iraq.

This is ancient Mesopotamia. The cradle of civilization. The epicenter of history. An embattled land in which war is as perennial as the seasons. Not far from here is the Gaugamela battlefield, where Alexander the Great’s army defeated the Persian army of Darius III in 331 B.C.

From this height, perched on a rocky escarpment, I easily can see the Kurdish peshmerga’s former front line against the Islamic State. The limit of the terrorist army’s advance seems close enough to touch, compared with the seemingly boundless and ancient expanse before my eyes.

The sun is scorching. Still, a chill spreads across my skin.

I think back to the Islamic State’s genocide of the Yazidis in Sinjar, and its destruction of the ancient city of Palmyra in Syria. It’s not hard to imagine what the Islamist militants would have done to this ancient and holy site had they reached it.

I also consider the grim fate that would have surely befallen the Christian inhabitants of the nearby villages. To say they narrowly escaped disaster is a gross understatement.

I descend again to the monastery’s inner courtyard where I find Naif resting on a bench in the shade. He’s got the right idea, I think, so I join him.

An effusively polite man who can’t shake the smile on his face, Naif sits forward with his hands clasped as we make introductions and quickly get to talking. I learn that, together with his wife of 11 years, Naif moved from Mosul to the nearby Christian enclave of Mergey in 2005.

“It wasn’t safe for Christians in Mosul, even before Daesh arrived,” Naif replies. “The fall of Saddam created chaos. Three members of my family were killed because they were Christian.”

A tile setter by trade, Naif landed a job at the monastery restoring some of the tile work. Still, he is frustrated, he tells me, because there’s not nearly as much work to be found in Mergey as there was in Mosul.

I ask Naif if he would ever consider moving back to Mosul, now that it’s been liberated. His reply is tellingly resolute.

“I can’t go back to Mosul,” he replies. “I don’t feel safe there.”

No Mercy

About 100,000 Christians lived in Mosul prior to the U.S. invasion in 2003. Roughly 5,000 remained in the city by the time of the Islamic State’s 2014 takeover. Of that number, nearly all left in the course of one night after ISIS issued an ultimatum, giving the city’s Christians 24 hours to either convert to Islam or be executed.

Like a gathering snowball, Christians from the surrounding towns and villages joined in with those fleeing Mosul as they trekked toward safety in Iraqi Kurdistan.

At that time, the monks at St. Matthew’s Monastery began to evacuate relics, including a priceless collection of centuries-old Syriac Christian manuscripts, as well as the supposed bones of St. Matthew, the monastery’s namesake.

With an attack on the monastery looking imminent, Naif and his wife fled their home in Mergey in the summer of 2014. At first, they headed for the Iraqi city of Duhok, within Kurdish controlled territory. They later shifted to a refugee camp, where they lived for two years.

“Daesh was very close. They were firing missiles and rockets at our village,” Naif says of ISIS. “We had no other choice. We wanted to live, so we left.”

St. Matthew’s shows signs that life is carrying on after the war. As it has for centuries, the monastery remains a place of worship and a refuge for Christians of all denominations. All the relics, including the bones, are back in their proper places.

The monastery maintains a furnished dormitory available for Christians from anywhere in the world to come and stay free of charge. On this day in May 2019, a few Christian pilgrims from Mosul mill about in the inner courtyard, performing their daily chores. Around midday, they retire to the chapel for prayers.

“The peshmerga are our heroes; they sacrificed their lives to save us,” Naif says. “Daesh has no mercy. They would have killed us all.”

Persecuted

The ongoing threat of violence has spurred a mass exodus among Iraq’s religious minorities, spurring what the Iraqi Human Rights Society has called a “slow genocide” among groups such as Christians and Yazidis. Now, these religious communities, which have existed inside Iraq for thousands of years, are at risk of disappearing altogether.

“It was reasonable to accuse ISIS of genocide a few years ago, as the U.S. and others in the international community did,” says Peter Mandaville, senior research fellow at Georgetown University’s Berkley Center for Religion, Peace, and World Affairs.

“The security environment in Iraq today is precarious and it is not difficult to imagine a new version of ISIS rearing its head within the next few years,” Mandaville says. “But most of the decline in Iraq’s Christian population cannot actually be tied directly to ISIS or any other militant group, but rather to broader political and security-related problems.”

Iraq’s Yazidi population has decreased by about 18%, according to a 2018 report by the Iraqi Human Rights Society. And Iraq’s Christians are at risk of extinction.

In 2003, between 1.5 and 2 million Christians lived in Iraq, representing roughly 6% of the country’s overall population at that time of about 25 million. Today, the number of Christians is down to around 225,000—about 0.006% of Iraq’s current overall population of more than 39 million.

The U.S., along with the United Nations and other international bodies, ultimately called the Islamic State’s crimes against religious minorities a genocide. Yet, many experts say the threat against Iraq’s religious minorities predates ISIS, underscoring a more complicated problem than the brutality of a single terrorist group and its acolytes.

“It is neglect of minorities by the state and widespread prejudice in society that helped create the conditions in which ISIS could undertake such atrocities, so the threat is broader and deeper than ISIS alone,” Cambridge University’s Monier says.

In March 2018, three Christians were stabbed to death in their home in Baghdad during an alleged robbery. The attack, which came shortly after a Christian was shot and killed outside his home in Baghdad, sparked fears among Iraq’s Christians that they were under attack once again.

This year, Islamic State sleeper cells have ratcheted up pressure on civilians across northern Iraq, threatening to burn farmers’ crops unless they agree to pay a blackmail tribute to the terrorist group. This resurgent threat spurred the Iraqi military to announce in March that it was arming the residents of 50 villages around Mosul to defend themselves against underground ISIS networks.

The Islamic State’s crop-burning extortion racket poses a particularly acute threat for many Yazidi communities in northern Iraq, which rely on subsistence farming to survive.

No Safe Quarter

After the 2003 U.S. invasion to topple dictator Saddam Hussein, years of sectarian violence left Iraq’s religious minorities in the crosshairs of Islamist extremists. Killings, kidnappings, torture, and acts of vandalism on religious sites spiked. In one particularly savage bombing in 2007, al-Qaeda militants killed 796 Yazidis and injured another 1,500.

“The largest exodus of Christians from Iraq occurred in the years immediately following the 2003 U.S.-led war in Iraq. This points to some of the deeper factors at work here, namely fundamental changes to Iraq’s political environment,” says Mandaville, the Georgetown University fellow.

Things got even worse after the Islamic State arrived on the scene in 2014. The Islamist terrorists singled out religious minorities for summary execution, torture, and rape.

“The removal of Saddam Hussein unleashed numerous localized rivalries and conflicts between groups that had been held in stasis due to the nature of his regime,” Mandaville explains, adding:

Christians no longer felt safe and did not believe there was a future for them in Iraq. This situation was exacerbated even further with the rise of ISIS. While the group certainly killed more Muslims than Christians or Yazidis, their targeting of Iraq’s small religious minorities was systematic and deliberate.

In 2014, the Islamic State invaded the Yazidi enclave of Sinjar in northern Iraq. The Islamist militants summarily killed thousands of Yazidis and kidnapped 7,000 women as sex slaves.

Seeking refuge from the onslaught, tens of thousands Yazidis fled to nearby Sinjar Mountain; many died there from exposure while waiting for help.

The Yazidis’ plight on Sinjar Mountain caught the world’s attention and ultimately spurred the U.S. to launch the coalition bombing campaign against ISIS called Operation Inherent Resolve.

With the help of those airstrikes, the Kurds fought through and opened up an escape corridor for the trapped Yazidis. By that time, however, about half a million Yazidis already had fled their homes to seek safety in Iraqi Kurdistan—with the overwhelming majority coming from Sinjar.

“Yazidis speak about 75 major attacks on their community throughout their history, and massacres and genocides are also prominent in the communal memory of Iraqi Christians,” Monier says. “However, the violence and the huge displacement that ISIS triggered is particularly horrifying, especially as it happened before the eyes of the international community.”

After two days of intense fighting, Kurdish and Yazidi forces backed by U.S. airstrikes liberated Sinjar in November 2015. The town, however, was reduced to a wasteland. The physical destruction was nearly total. And amid the ruins, the liberating Kurds unearthed close to 100 mass burial sites.

Even with the Islamic State’s demise, few Yazidis are willing to go home. A 2019 U.N. report found that only 3% of Yazidis displaced from Sinjar planned to return in the next year. According to the study, they don’t believe the threat is gone for good.

“Yazidis are reluctant to return home,” the Free Yezidi Foundation’s Ibrahim says, speaking of those displaced from Sinjar.

“Surrounding villages, en masse, joined ISIS,” Ibrahim says, adding:

ISIS members remain throughout different areas. The whole of Sinjar remains largely in rubble. But even if they reconstruct it, there are a handful of different militias with power in different areas. They don’t like each other, and Yazidi civilians have to struggle to find who to trust. It is not like a normal country.

The Peacock Angel

An ethnic Kurdish minority indigenous to Iraq, Syria, and Turkey, the Yazidis number between 500,000 and 1.5 million worldwide.

Like Iraq’s Christians, over the centuries the Yazidis have clustered into tight-knit communities for protection. Their culture is insular—marrying outside the religion or caste system is forbidden under penalty of excommunication.

The Yazidis’ monotheistic faith originated in Mesopotamia more than 4,000 years ago. Rooted in Zoroastrianism, it incorporates elements of Christianity, Islam, and Judaism. Elements of Hinduism also are evident in their traditions and myths.

The Yazidis worship the “peacock angel,” which, according to some scholars, corresponds to Satan in the Abrahamic religions. The Islamic State singled out Yazidis as devil worshippers and treated them with a singular degree of brutality.

The Yazidis’ holiest site is the mountainous town of Lalish, about 30 miles from Mosul in Iraqi Kurdistan. Each year in Lalish, the Yazidis celebrate the Feast of the Assembly, a seven-day pilgrimage in late September to the tomb of Sheikh Adi Ibn Musafir, the 12th-century founder of Yazidism. All Yazidis aspire to attend the festival at least once in their lives.

On this day in late May, Lalish brims with activity. Old men share a bench, speaking with emphatic hand gestures. Children play while their parents lounge in the shade of giant olive trees.

A few young men work the counter at a snack stand. On the wall behind them is a mural of Noah’s Ark. I notice the image of a black snake painted on the hull. Curious, I ask about the snake.

According to Yazidi tradition, I learn, a black snake plugged itself into a hole in the ark’s hull, ensuring the future of all living beings. For that reason, the Yazidis treat black snakes with holy reverence.

Shoes are forbidden in Lalish, even when outdoors, to preserve the sanctuary’s purity. My feet, softened by easy living, suffer at first but soon get used to the smooth stone walkways.

I gingerly make my way to the mausoleum of Sheikh Adi Ibn Musafir. Supposedly built thousands of years ago, the temple was converted to a mausoleum in 1162. Today, it is the world’s holiest place for Yazidis. The entry portal is made from marble quarried from Mosul; a relief depicting a black snake is beside the door.

I am careful not to step on the raised threshold of the doorway as I enter the temple. Yazidi pilgrims stoop and kiss thresholds, but never step on them. I forego the kiss, but watch where I place my bare feet.

I remark that in Ukraine, according to tradition, some people never shake hands or exchange goods across thresholds. They either go all the way out the doorway or come all the way in.

According to old superstitions, evil spirits living under the threshold can steal your financial success, or even your soul. I wonder—could these cultural quirks have some common, ancient provenance?

Inside the Yazidi temple it’s dim and quiet, although the voices of pilgrims echo in the stone space.

Colored cloths are wrapped around some of the pillars. The cloths are of six colors—one for each of the seven colors of the rainbow except for blue, symbolizing the seven holy angels of the Yazidi faith. (For reasons unknown to me, Yazidis refrain from wearing the color blue.)

These colorful cloths are tied in many knots. Each knot represents a wish. To make your own wish, you must first untie a knot, allowing someone else’s wish to come true. Then, you make a wish and tie your own knot three times.

I go through the motions, leaving a knot and its attendant wish behind for someone else to untie someday.

Deeper into the temple, I enter a shadowy room and come across a group of young men who intermittently take turns tossing a silken handkerchief toward a small stone shelf. They do this with their eyes closed. If the handkerchief stays on the shelf, according to tradition, the thrower will get married soon.

One of the young men closes his eyes, exhales at length, and lets the silk cloth fly. It sticks! The others around him cheer in delight and offer an impassioned round of back slaps and handshakes.

As I make my way through the temple, another young man follows me. He stays a few paces behind, walking with his hands clasped behind his back. He never intrudes or interferes, but he’s definitely keeping an eye on me.

To be polite, I stop and introduce myself. The young man returns the greeting and introduces himself as Barzan Shamdin. He is 18 and from Sinjar, he says, and lives with his family in a camp for internally displaced persons near Lalish.

Shamdin tells me he is grateful for the Kurdish peshmerga fighters and the U.S. pilots who saved his people from destruction.

“We are a minority and we cannot protect ourselves,” Shamdin says. “We will love forever everyone who fought to save us.”

I ask Shamdin why he hasn’t gone home yet. If the Islamic State is defeated, why is he still living in a camp?

“My whole family, like all Yazidis, wants to go home,” Shamdin tells me. He pauses for a beat, then adds: “We know that Daesh is gone. But we don’t feel safe enough to go back.”

‘Religion Unites Us’

From Lalish, the road I follow cuts south and then west across the Nineveh Plains to arrive at the ancient Christian town of Alqosh. The two-lane highway into town passes through a Kurdish checkpoint and under a metal arch topped by a Christian cross.

Originally a Jewish settlement, Alqosh became a Christian enclave as early as the first century, some scholars believe. Today, the town has a population of about 15,000, most of whom are Christian.

Evidence of Alqosh’s antiquity is clear. The town is a tangled mess of ancient buildings interwoven with narrow alleyways conceived long before automobiles were ever part of the picture. New construction simply melds into the crumbling remains of the old.

There also is no mistaking the town’s Christian heritage. Murals depicting images of Jesus Christ, or of the cross, are prolific.

During my wanderings, I curiously venture through a nondescript entranceway of cut stone. It leads through a narrow passageway and into the inner courtyard of the fifth-century Mar Mikha Church. The surrounding walls are cracked and crumbling in places. The graves of monks and priests are beneath the weathered stone floor.

I take a moment to appreciate the sanctity of this historic, holy site. Then, as I’m about to leave, a man exits the church’s office and invites me in for a glass of water. Naturally, I agree.

The man, whose name is Basaam Shasadda, is a 39-year-old Christian who used to live in Mosul. He’s a little surprised to discover an American journalist wandering through his church, but he’s eager to chat.

I ask about the lingering threat posed to Alqosh’s Christians by remnants of the Islamic State. He replies: “The Daesh threat isn’t just to Christians; all of Iraq is unstable. But when there’s an attack, it’s usually on the religious minorities.”

When ISIS invaded to within a few miles of Alqosh in 2014, most of the town’s population evacuated. Only a few hundred people stayed behind, Shasadda says:

Everyone was frightened when Daesh was advancing. But I stayed. I stayed because this is my home. We didn’t leave for Saddam, and we weren’t going to leave for Daesh.

For Shasadda, the lingering threat of ISIS sleeper cells is too high for him to consider returning to Mosul. Plus, he says that within Iraqi Kurdistan, Christians live in peace alongside the Kurds. There’s no point, in his mind, to abandon the relative safety he enjoys in Kurdish-controlled territory.

“We are treated equally in Kurdistan. We are treated the same as anyone else,” Shasadda says. “We are all able to live together peacefully—all the different religions.”

Yet, Shasadda laments the mass exodus of Christians from Iraq. And he worries that although Alqosh dodged a bullet in 2014, the roots of Islamist rage that spurred the formation of the Islamic State have not yet been erased.

Thus, the survival of Iraq’s Christian population is not a foregone conclusion, Shasadda says. Striking a defiant note, however, he says he believes the war unified Alqosh’s Christian community, increasing its resilience to deal with another crisis.

“It’s difficult to have hope that things will get better, and I don’t know what the future holds,” he says. “But the church keeps us together as one. Religion unites us.”

A Hopeful Sight

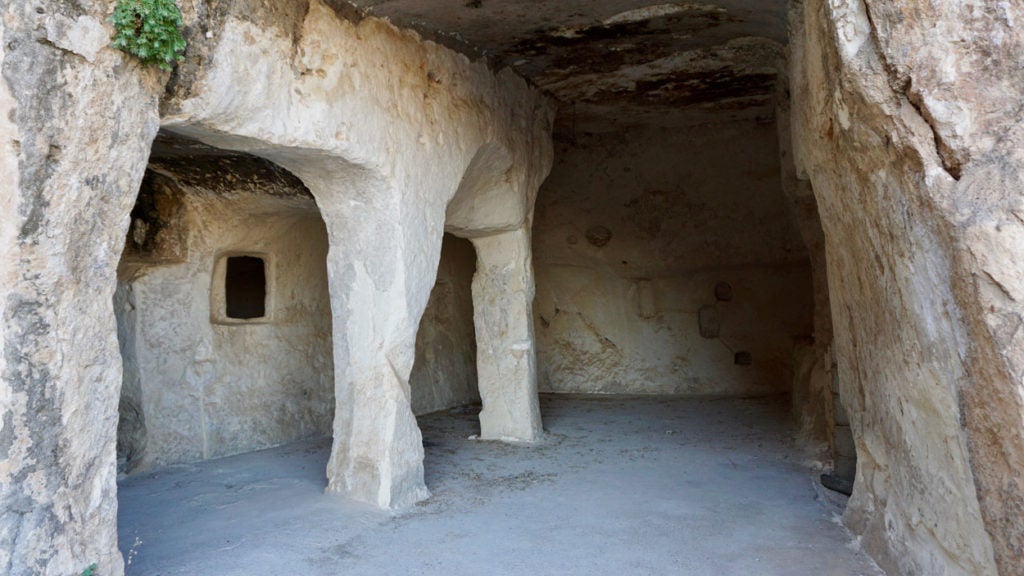

Leaving Alqosh, the road climbs north toward the nearby mountains. I enter a narrow defile and observe the Rabban Hormizd Monastery built into the steep, rocky slopes above. It’s an impressive sight to behold.

Founded in 640, this Chaldean Catholic Church monastery has been abandoned and rebuilt multiple times over the centuries. Today, the fortress-like structure is no longer an active monastery, but remains a popular place of worship for the Christians of Alqosh.

During the war, people would also visit the monastery to witness the mushroom clouds of coalition airstrikes ascend above Islamic State-controlled territory to the south.

On this evening, the sun already has dipped behind the mountains, casting the monastery in shadow. Looking south, the rolling plains in the direction of Mosul are still bathed in sunlight. There’s no evidence of war.

Rather, a group of Christians has gathered on the monastery’s terrace to enjoy the evening and freely exercise their faith. The adults sing songs and chat. The children play and laugh.

Observing this joyful scene, I think back to what Shasadda told me as we parted ways a short while earlier:

“We survived.”