What Social Security’s Shortfall Means for You

Rachel Greszler /

Workers and retirees have long been warned that Social Security’s trust fund will run out of funds sometime in the future, and that the program has many trillions of dollars in unfunded obligations.

But what does this year’s 2019 Trustees Report, revealing $16.8 trillion in unfunded obligations over the next 75 years and insolvency in 2035, mean for current workers and retirees? (The $16.8 trillion figure includes the $13.9 trillion 75-year unfunded obligation, plus $2.9 trillion in trust fund IOUs that represent additional debt.)

Well, for starters, 2035 is only 16 years away. That means that anyone below the age of 52 today is on track to receive only 75% to 80% of their scheduled benefits.

But it’s not just younger workers who will receive benefit cuts. Consider people who are retiring in 2019 at age 62: Benefit cuts will kick in for them at age 78.

Social Security’s insolvency is not some far-off event. It will affect virtually all current and future workers and many of today’s current retirees.

Now, let’s move on to the magnitude of Social Security’s $16.8 trillion shortfall.

That’s the equivalent of $107,000 for every worker in the U.S.—roughly two times the average earnings.

That’s also enough to turn young workers into millionaires. If Sara, who just started her first job out of college, put $107,000 into a retirement account and never added another penny, she would have $1,000,000 upon retirement (assuming a 5% real rate of return).

Unfortunately, though, today’s workers are starting out in the hole, instead of ahead of the game.

In addition to already paying 12.4% of their paychecks to Social Security, current workers will either have to pay drastically higher taxes—as much as 33% more—or receive lower benefits.

If Congress acted today to make Social Security solvent through a 22% tax increase, Terrence, another young worker who makes $50,000 per year, would pay an extra $1,400 in taxes each year (an increase from $6,200 to $7,600 per year).

If Congress fails to do anything until the trust funds run out of reserves in 2035, Terrence’s payroll taxes would have to rise by 29%, and he would pay $1,800 more per year ($8,000 total in Social Security taxes).

What if Congress cuts benefits instead?

That would translate into about $57,600 less in benefits for Terrence (assuming he lives to age 82) if Congress were to cut all benefits by 17% immediately, and almost $78,000 less in benefits if Congress waits until 2035 and cuts benefits by 23%.

So, should workers hope that Congress increases taxes to preserve their scheduled benefits or reduce benefits to prevent tax hikes?

Analysis by my colleagues and me at The Heritage Foundation provides a resounding case for not raising taxes (and instead implementing gradual and targeted benefit reductions).

The reason for that lies predominantly in the fact that Social Security is an intergenerational transfer program, as opposed to a savings program. Every single dollar of the $1 trillion that workers paid in Social Security taxes in 2018 is already in retirees’ hands.

Talk about sapping workers out of opportunity and investment. These taxes—which many workers perceive as savings—never even have a chance to earn a positive return.

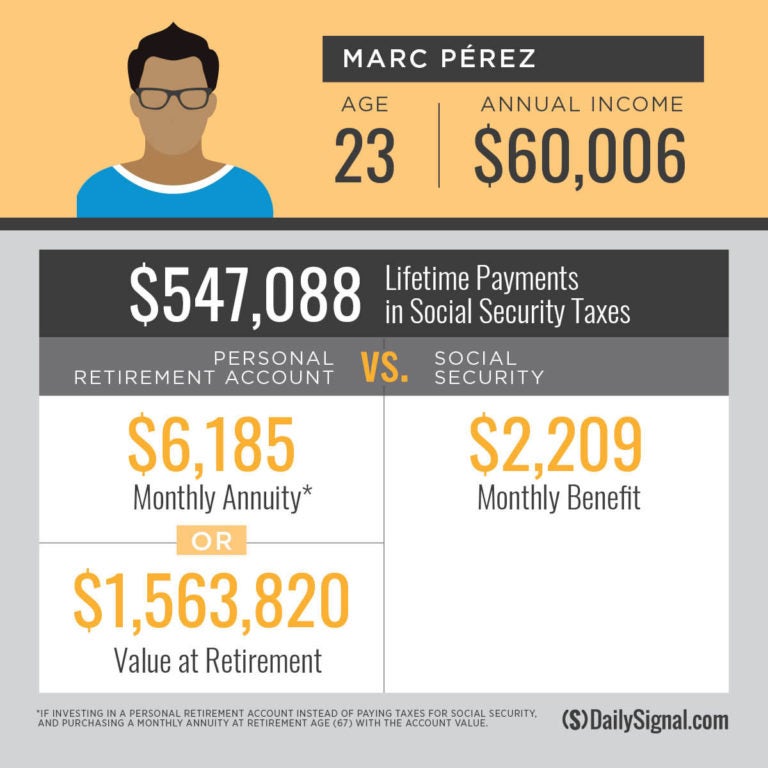

Our analysis showed that if Marc, a 23-year-old with $60,000 in annual earnings, were to invest his Social Security taxes on his own, he would accumulate a retirement account worth $1.56 million.

If Marc wanted the safety of a guaranteed annuity, he could use this account to purchase an annuity that would provide more than $6,000 per month—nearly three times the $2,200 benefit that Social Security would provide.

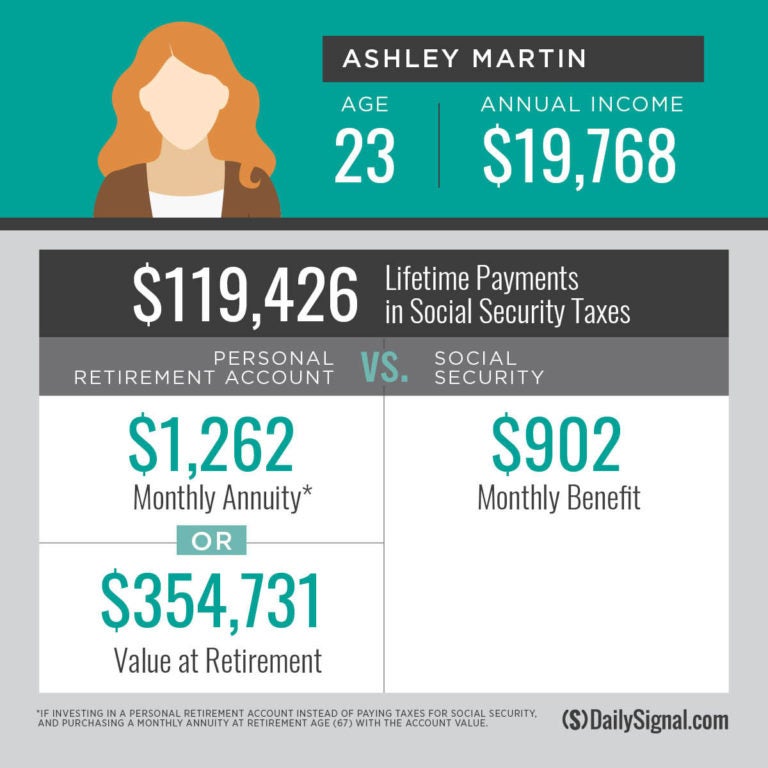

Even low-income earners who receive higher returns from Social Security would be far better off with lower taxes and more personal savings.

If Ashley, a 23-year-old with just under $20,000 in annual earnings, had the opportunity to invest her payroll taxes on her own, she would accumulate a $355,000 retirement. That account would be enough to purchase an annuity that would provide her with $1,260 per month, or 40% more than the $900 Social Security will provide.

The aim of this analysis isn’t to end Social Security entirely and let workers keep all of their payroll taxes, but is meant to make a compelling case that extracting ever-increasing portions of workers’ paychecks is both harmful to workers and beyond the intended scope of the program.

Congress should reorient Social Security in ways that protect and improve benefits for the most vulnerable while increasing incomes and opportunities for all workers by limiting Social Security’s drag on their paychecks.

The Heritage Foundation has a plan that will accomplish the latter—making the program solvent and reducing Social Security’s tax rate by 13 percent in the long run—by gradually shifting to a universal anti-poverty benefit, tying Social Security’s retirement age to increases in life expectancy, using a more accurate inflation index, and modernizing the program.

Stay tuned for the full analysis of our proposed reforms in this year’s Heritage Foundation “Blueprint for Balance,” set for publication on May 20.