New Data Bucks Conventional Wisdom on Free Markets and the Environment

Patrick Tyrrell / Miguel Pontifis /

Politicians on the left are pushing a radical “Green New Deal,” which they say is necessary to save the environment. It wouldn’t save the environment—though it would do serious damage to our economy.

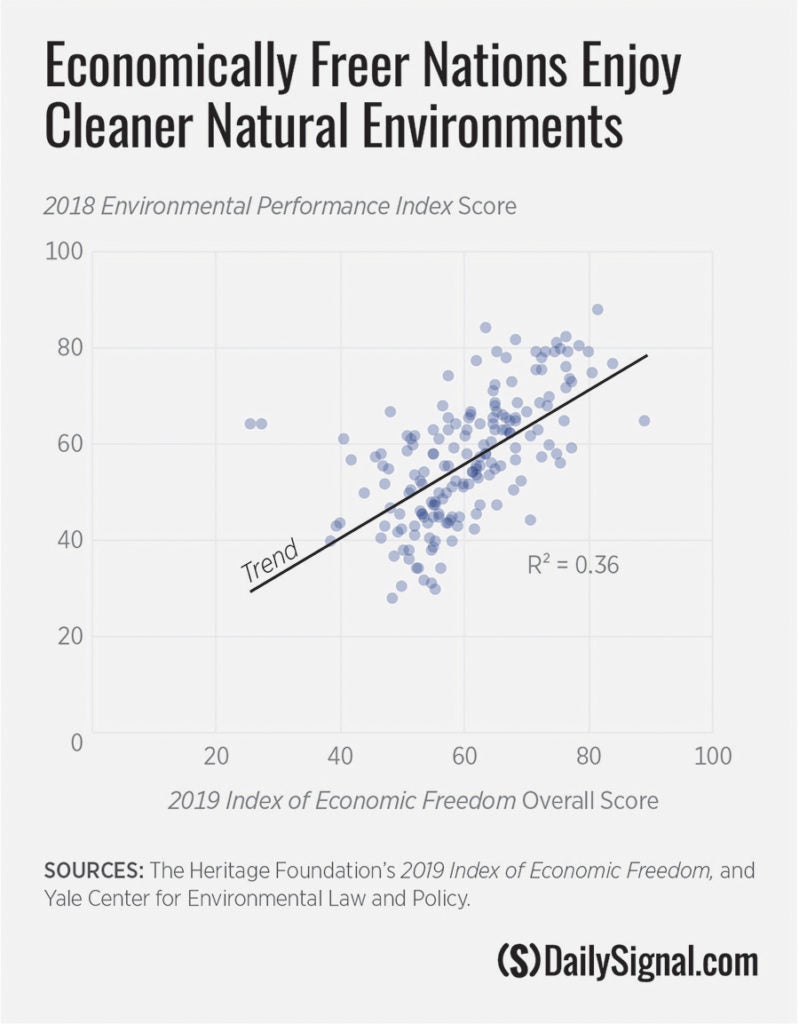

The surprising truth is that saving the environment and improving the economy are not at odds. In fact, new research from The Heritage Foundation using data from the Yale Center for Environmental Law and Policy shows that economic freedom and environmental protection tend to go hand in hand.

In countries where people are economically freer, the environment is generally cleaner, as seen in the chart below.

This flies in the face of the Green New Deal, which aims to “mobilize every aspect of American society on a scale not seen since World War II”—translating into less economic freedom and more government control.

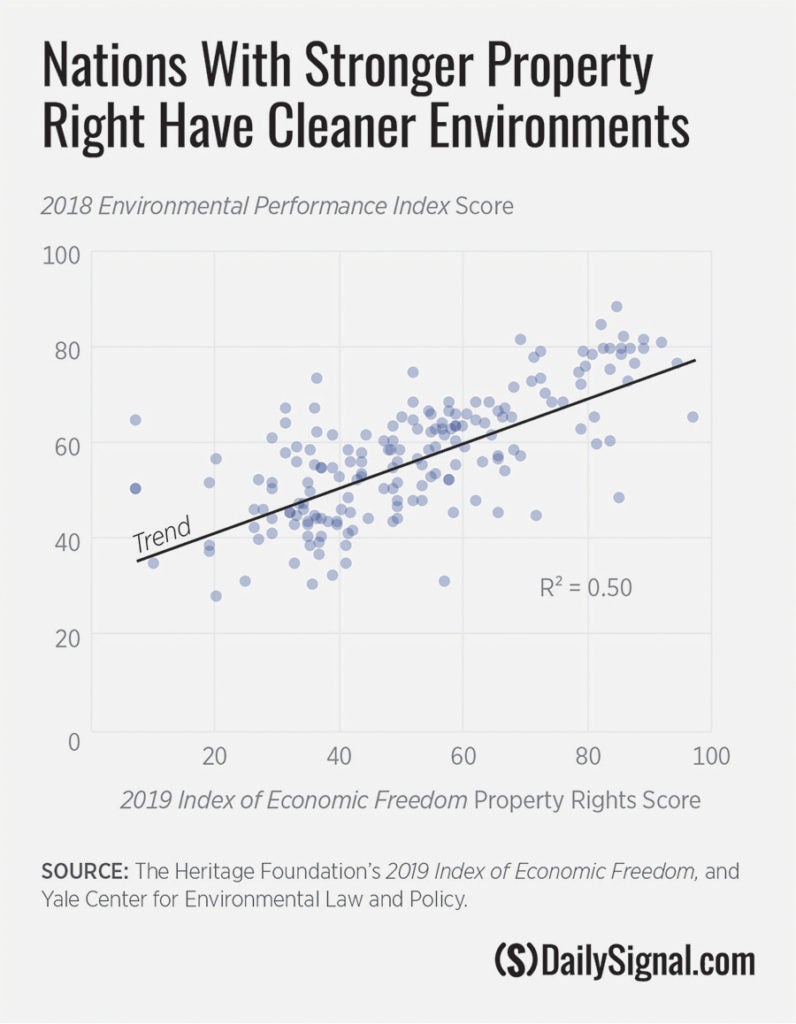

Even more striking, however, is the strong correlation that exists between private property rights and environmental protection. Countries that protect private property rights are highly likely to have cleaner environments as well, as the chart below illustrates.

Furthermore, three of the top 15 leaders in property rights in the 2019 Index of Economic Freedom—Switzerland, Sweden, and Ireland—also lead in the Environmental Performance Index, and all three have greater resource preservation, better air quality, greater bio diversity, and more pristine natural habitats.

>>> Check out The Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom

This data may come as a surprise to some. What explains this high correlation between property rights and environmental stewardship?

Two things.

First, a legal system that protects private property offers greater incentives for people to maintain or convert their personal property into its highest valued use—not just in the present, but into the future as well. Put simply, a profitable enterprise must be a sustainable enterprise.

And second, a system that protects private property rights naturally holds people accountable for the way they use their resources and manage their assets. Property owners have a personal stake in keeping up the quality of their environmental property, since their own wealth is tied to it. That is not the case with public lands, where no one has a unique stake in the upkeep of the land.

Forests are a prime example. When property rights are weak or nonexistent, companies won’t be able to bank on having legal ownership of land years down the line, so they may opt for short-term profit and clear-cut the land—thereby ruining the environment.

But with strong property rights protections, property owners are less likely to deforest the land because they have to consider their long-term means of profit, not just the short term. In opting for the long term, they will protect the land for future generations to enjoy.

Many politicians wish to save the environment, and many are well-meaning. But the most up-to-date research shows that the key to environmental stewardship is not in more government control, but in greater economic freedom and protection of property rights.

It turns out that greater freedom and liberty isn’t just good for human flourishing, but for the environment as well.