New Study Dispels Misconceptions About ‘Motherhood Penalty’ and ‘Fatherhood Premium’

Rachel Greszler /

When a couple has a child, the woman’s earnings tend to decrease, while the man’s increases. This is known as the “motherhood penalty” and “fatherhood premium.”

Economists have pegged the resulting gap at about 20 percent of earnings over the long run, due to changes in labor force participation, hours of work, and wage rates.

Advocates of complete pay parity conjecture that gender-based discrimination is to blame for the gap in pay between mothers and fathers, suggesting that employers wrongly perceive women as less valuable once they become mothers and fathers as more valuable.

Fresh evidence from a study by Valentin Bolotnyy and Natalia Emanuel of Harvard University suggests the “motherhood penalty” and “fatherhood premium”—at least at the level experienced in this study—is the result of choices mothers and fathers make, and not gender-based discrimination.

The study, “Why Do Women Earn Less Than Men? Evidence from Bus and Train Operators,” examined the earnings and hours of male and female operators within the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority.

The unionized environment within the transportation authority prohibits gender-based discrimination. Even if a manager wanted to discriminate, they couldn’t, because pay and workers’ options depend exclusively on tenure.

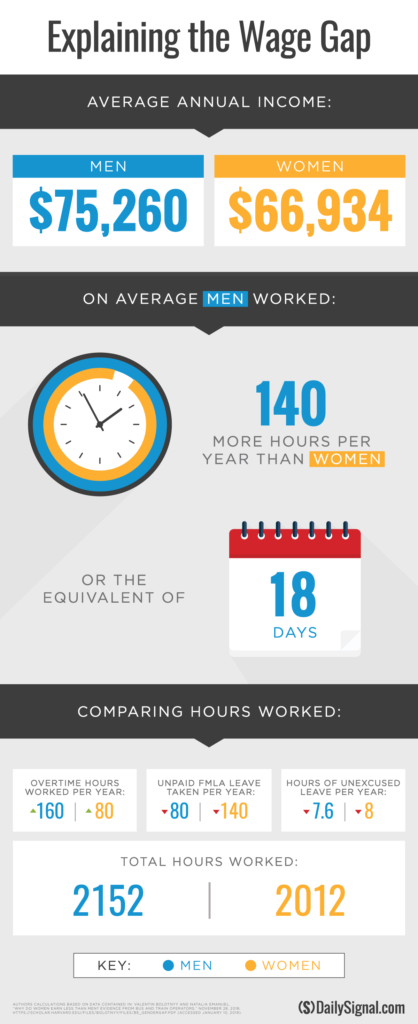

Despite the rigid pay system, women made 11 cents less, 89 cents on the dollar, compared with men.

The authors concluded that the gap “can be explained entirely by the fact that, while having the same choice sets in the workplace, women and men make difference choices.”

As a whole, women chose to work only half as many overtime hours—80 hours per year, compared with 160 hours for men.

Women also took an average of 17.5 days of unpaid leave (often to avoid undesirable schedules) through the Family and Medical Leave Act, compared with 10 days of leave for men. (The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 requires employers with 50 or more employees in the U.S. to grant up to 12 weeks of unpaid leave a year for family and medical purposes.)

More overtime pay and fewer days of unpaid leave resulted in higher average weekly earnings for men.

Looking specifically at the gap between mothers and fathers, the study concluded that “women with dependents—especially single women—value time away from work more than men with dependents.”

While women become less willing to work overtime and more likely to take unpaid FMLA leave after becoming a mother, men accept more overtime work and take less unpaid leave.

Stereotypical as it may be, the average woman responds to motherhood by wanting to spend more time with her family, while the average man responds to fatherhood by wanting to spend more time providing financially for his family.

This is an important finding. Past studies have found a nonlinear gap in earnings within certain occupations based on flexibility and hours worked, particularly when it comes to highly paid occupations, such as law and medicine.

This study shows that flexibility and hours play a significant role for workers with average earnings and hours as well.

Moreover, the study found that some policy changes that reduced the earnings gap actually left women and men worse off.

The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority implemented two policies: one making it more difficult to take FMLA at a moment’s notice and another limiting workers’ ability to game overtime hours.

These changes reduced the earnings gap from 11 cents to 6 cents on the dollar, but at the price of reduced workplace flexibility and a significant reduction in earnings for both men and women.

As noted by the authors, “Because women have greater revealed preferences for this flexibility, women likely fared worse from these policies than men.” Instead of taking FMLA leave, women took more unexcused leave when their schedules did not meet their needs or desires, but unexcused leave can result in suspensions or termination.

The authors suggested that allowing workers to trade shifts could improve workplace flexibility without hurting performance.

Another policy that would help workers without hurting companies is the Working Families Flexibility Act. That bill would allow private-sector employers to provide their workers with the option of taking time-and-a-half pay or time-and-a-half paid leave when they work overtime hours.