House Democratic Rules Package Could Mean More Spending, Higher Taxes

Justin Bogie / Romina Boccia / Adam Michel / Rachel Greszler /

As Congress gears up for the new term, the House of Representatives is preparing a vote this week on rules to govern the 116th Congress.

A few notable provisions are grabbing the headlines, such as allowing the speaker to “intervene” in challenges to Obamacare, establishing a new select committee on climate change, and making it harder to call for a mid-session vote for speaker. But several provisions impact the federal budget, and not for the better.

Rather than promoting fiscal restraint, the House is considering rules changes that would move in the opposite direction. The results could mean more deficit spending and higher taxes for many Americans.

Here are four proposed rules changes the House should reconsider.

1. Adoption of a “Gephardt rule,” which would allow the House to avoid a direct vote on the debt limit.

Under this rule, a vote on a House budget resolution would double as a vote to raise the debt limit in the House. In early 2019, we are likely to hit a debt of $22 trillion. Americans deserve a true stand-alone vote on the debt limit in both chambers of Congress.

The debt limit is an important moment for forcing action to confront our nation’s highly unsustainable and worsening fiscal path, and an opportunity to correct course with spending and entitlement reforms. The Gephardt rule would reverse course by allowing the House to avoid taking an important vote on the debt limit, thus reducing congressional accountability.

The version considered by the new House in its rules package would send a debt limit suspension through the end of the fiscal year (Sept. 30) to the Senate upon passage of a concurrent resolution on the budget in the House.

Congress should enact fiscal controls to reform and control spending, and should do so before increasing the debt limit again.

2. Eliminating dynamic scoring.

The proposed rules package would eliminate a requirement that major legislation take into account the economic impact of the policy changes it contains. The official score of how tax legislation affects revenue would no longer take into account how policy changes affect the way people, businesses, investors, and entrepreneurs alter their behavior in response.

This would deny the widely accepted reality that government policy can and does change people’s behavior and affect the economy. In essence, it would allow Congress to ignore the negative effects of its own policies.

Getting rid of dynamic scoring would make it easier for Congress to raise taxes on all Americans. Lawmakers would be able to pretend that higher tax rates will bring in lots of new revenue, while denying the negative effects of a slower economy.

Raising income tax rates would bring in more revenue, but it would also cause people to work less, save less, and invest less. When people work less, the government collects less revenue and the economy as a whole is smaller than without the tax hike.

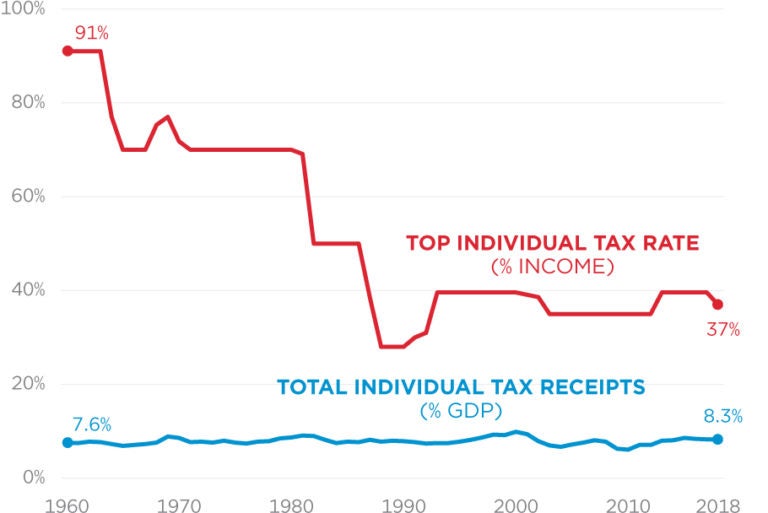

Top marginal income tax rates have been as high as 91 percent and as low as 28 percent over the past 50 years, but the resulting revenue hasn’t changed that much.

(Photo: Federal Budget in Pictures)

(Photo: Federal Budget in Pictures)

3. Removing supermajority protection against tax increases.

The proposed House rules would strike the requirement that a supermajority of three-fifths of Congress vote to increase taxes on the American people. Without this protection, the House would be able to more easily increase income taxes, endangering the tax cuts passed a year ago.

4. Allowing amendments to appropriations bills that increase net spending.

Under current House rules, an amendment to a spending bill cannot cause a net increase in budget authority. In other words, any proposed amendments that would increase or create new spending must be fully paid for.

The new rules package would abandon that requirement, and it couldn’t come at a worse time. The Budget Control Act spending caps, one of the few tools to restrain spending, are on life support. Absent these caps, Congress may pass billions of dollars in unpaid spending.

The deficit is already likely to top $1 trillion this year. Now is not the time to make it easier for Congress to heap on more spending.

Rules changes are an opportunity for Congress to take on more budget restraint and transparency. Here are three alternative rules changes that would further those goals.

1. Account for interest costs when considering legislation.

Under current scoring conventions, Congress does not require the Congressional Budget Office to include the additional interest costs of changes to spending and tax levels. This creates an incomplete view of the costs of legislation and distorts congressional decision-making in favor of more spending and debt accumulation.

Congress should direct the Congressional Budget Office to produce interest cost estimates to accompany every score of proposed legislation. This would improve accuracy in scorekeeping and help Congress make more informed decisions.

2. End unauthorized appropriations.

Last year, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that Congress appropriated over $300 billion to programs with lapsed or “zombie” appropriations. The authorization process is an oversight tool that provides a chance for members of authorizing committees to closely examine federal activities and determine whether or not they are worthy purposes.

Yet Congress has only weak rules to limit zombie appropriations and they are ignored.

Congress should pass a stronger rule that ends unauthorized appropriations. Oversight is one of the major duties of members of Congress, and by failing to take action for or against authorizations, it is doing a disservice to taxpayers. With the national debt quickly approaching $22 trillion, the country cannot afford to waste any more money on zombie appropriations.

3. Reinstate the Holman rule.

The Holman rule gives Congress a more inclusive process for allocating funds as it intends. It allows Congress to cut specific funds from an appropriations bill, to reduce the number of federal workers in a particular agency or program, or to cut the pay of a particular federal worker.

Although critics of the rule wrongly claim that it would upend the civil service system and lead to all sorts of targeted job and pay cuts, that is neither the purpose of the rule nor how it has been used when in place. Instead, the Holman rule allows legislators to eliminate programs they do not intend to fund; to eliminate positions or reassign workers based on government priorities; and to cut the pay of workers in particularly egregious cases.

Today, federal employees’ unions make it nearly impossible to fire a federal worker—even in cases when the worker has confessed to a crime. Federal employees’ jobs should not be immune from an act of Congress signed by the president. The Holman rule ensures that if a federal employee performs so severely that both Congress and the president call for action, the employee can effectively be forced to resign by reducing his pay to $1.

More importantly, the Holman rule allows lawmakers to key in on their intended spending priorities and protect taxpayer resources by cutting funding for unnecessary or problematic programs.

Each new session of Congress provides an opportunity for the House to re-evaluate its rules and set the agenda for the next two years. If the rules set forth for the 116th Congress are any indication, it could be a costly two years for taxpayers.

Instead of adopting rules biased toward higher spending and taxes, the House should adopt a package promoting fiscal responsibility and transparency, paving the way for overdue spending reforms.