Errant Phone Message Is a ‘Text’-Book Case for Voter ID Laws

Jason Snead /

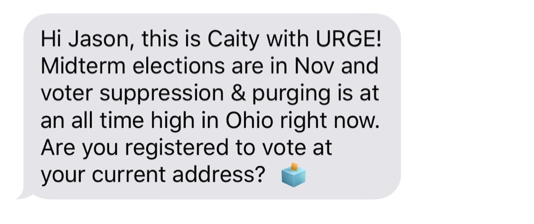

I got an alarming text message a few weeks ago from an Ohio phone number I didn’t recognize.

Someone—or perhaps some robot—named Caity, from a group called Unite for Reproductive & Gender Equity, had an urgent message for me: “[V]oter suppression & purging is at an all-time high in Ohio,” the text read in part. “Are you registered to vote at your current address?”

Caity, it seems, is not a fan of efforts in Ohio—or elsewhere—to clean up its voter rolls, remove inaccurate entries, and ensure the integrity of the election.

She and activists like her should think twice about that conclusion, because Caity’s text inadvertently proves the necessity of such measures.

That’s because I’m not an Ohio voter. To be fair, I can understand the confusion for an activist who somehow obtained my records and targeted me for a get-out-the-vote campaign.

Yes, I am from Ohio, and my family still lives there. Yes, I went to school at Bowling Green State University. And yes, I have a phone number with an Ohio area code.

But years ago, I did what millions of Americans do every year: I moved out of state and changed my residency to my new home state of Virginia. Given the circumstances, assuming me to be a valid resident of Ohio was an easy mistake for Caity to make.

The problem is, it would be an easy mistake for a poll worker to make, too.

How so? For starters, voter rolls throughout the U.S. are in poor shape.

In 2012, the Pew Center for the States concluded that 1 in 8 voter registrations—24 million in total—were wrong or outdated. An additional 2.75 million people were registered in multiple states, and 1.8 million people remained on the rolls after their deaths.

That situation does not seem to be improving on its own. In fact, Californians recently discovered that the state Department of Motor Vehicles had improperly registered 1,500 people, including noncitizens, and botched or duplicated the registrations of tens of thousands of other residents.

Wildly inaccurate voter rolls make it harder for election officials to screen out unlawful participants, and create new avenues for would-be fraudsters to cast illegal ballots.

Worse still, many states have no or inadequate voter identification requirements, making it even more difficult to detect ineligible people who cast ballots, vote more than once, or vote in the name of others.

Liberals might insist that election fraud does not occur, but a simple search of The Heritage Foundation’s election fraud database proves that assertion false.

Including its newest additions, the database now tallies 1,178 proven instances of fraud, including more than 1,020 criminal convictions.

Consider the case of Hannan Yassi Aboubaker, who in 2016 submitted an absentee ballot in Minnesota and then voted in person in North Dakota. She entered an Alford plea to a misdemeanor election offense, meaning she did not admit guilt, but did acknowledge enough evidence existed to convict her. Her sentence was deferred, and she was placed on probation for six months.

Last year, Carson Lee Tuttle pleaded guilty to an illegal voting charge after he, too, voted twice in the 2016 election—by absentee ballot in West Virginia and in person in Ohio. He was fined and ordered to pay court costs.

Situations like these prompted Ohio lawmakers to create a mechanism to remove old voter registrations on the grounds that a particular voter is no longer a resident of the state.

The process Ohio uses is deliberate and requires the state to attempt to contact the voter to confirm whether he is still an Ohioan.

In all, a voter has to take no part in any election activity in the state for two years, and then again for two consecutive federal election cycles, before he or she can be removed from the rolls.

Does that amount to wanton voter purging and sinister disenfranchisement? Hardly. Yet Ohio was challenged by liberal activists, who fought the state all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ultimately upheld Ohio’s efforts.

Undeterred, those same activists are continuing to challenge election integrity efforts in Ohio, while other groups do the same thing throughout the nation.

For all their outrage over “voter suppression,” these activists ignore the very real disenfranchisement that election fraud causes.

What else could one call it when a community’s voice is silenced by a politician who steals an election, or a lawful voter’s ballot is negated by an illegal vote?

Activists, for their own political advantage, want voters to fear good-faith efforts to secure the ballot box against fraud and theft.

Voters lose when those efforts succeed.