In 5 Points, a Former Drug Czar’s Prescription to Combat Opioids and Pot

Troy Worden /

America needs leaders who will actively discourage recreational drug use and promote “meaningful prevention” and recovery, a former White House drug czar said in remarks to a Heritage Foundation audience.

Public debate over opioid deaths and legalized marijuana could spur real change in how society approaches public health, Robert L. DuPont said in his appearance Tuesday at the think tank’s Capitol Hill headquarters.

“This is a historic opportunity,” he said.

“I think we need leadership that actively discourages recreational pharmacology … and promotes recovery and meaningful prevention.”

DuPont, the first director of the government’s National Institute on Drug Abuse, emphasized points he makes in his new book, “Chemical Slavery: Understanding Addiction and Stopping the Drug Epidemic,” which grapples with understanding and managing drug addiction at the personal and national levels.

Before heading the drug abuse agency within the Department of Health and Human Services, DuPont was White House drug chief—popularly known as the “drug czar”—under President Richard Nixon.

“Listening to Dr. DuPont discuss drug policy is like listening to Mozart direct a symphony,” Paul Larkin, a senior legal research fellow at Heritage, said in introducing DuPont, a practicing psychologist for over 50 years.

Here are five of DuPont’s key points and topics.

- ‘Commercialized Recreational Pharmacology’

DuPont began by defining the key problem of addiction from a health policy standpoint. He calls it “commercialized recreational pharmacology,” or the industry that developed around humans’ use of chemicals that produce effects in the brain.

Americans spend three times as much on illegal drugs ($100 billion) than they do on drug treatment ($32 billion), he said, and 95 percent of addicts initially don’t see their addiction as a problem.

DuPont stressed that humans are unique in the animal kingdom for their engagement in recreational pharmacology, and that addiction changes the addict in profound ways. He characterized the addict’s mental state as that of the “hijacked brain.”

“It’s a completely different person,” DuPont said, in comparison with who the person was before addiction. The thinking and priorities of an addict are quite different than those of an unaddicted person, he said.

- The Meaning of ‘Recovery’

DuPont said that because recovery produces a different person from the addict, it doesn’t mean just quitting drugs.

“The story of recovery has three parts,” he said. “What your life like was like when you were using. What happened to get you to stop. What you’re like now that you’re not using.”

An addict usually doesn’t stop unless he repeatedly finds himself in a bad situation, DuPont said.

He stressed that recovery never ends, hence we shouldn’t refer to an ex-addict as “recovered” but “recovering.”

“The risk of relapse goes on forever,” he said.

“We’ve decided that relapse is a part of the disease,” DuPont said, but should really be asking ourselves: “How good can outcomes be?”

In support of his claim, he offered up the example of physician health programs, which have high rates of long-term recovery. Physician health programs rehabilitate and monitor doctors who abuse alcohol and other drugs, or who suffer from mental or physical illnesses.

These programs have such success rates, DuPont said, because they hold the physicians that go through them accountable in a variety of ways. These include random drug tests over a five-year period, the threat of losing their medical license should they fail a drug test, and recovery support programs long after the treatment’s end.

Preventing use of a drug after treatment is a major factor in whether recovery is sustained, DuPont said.

“Every treatment should be evaluated on its ability to move people into lasting recovery,” he said.

This standard does not mean that patients have to be off medication entirely, he said, but off the drug to which they are addicted.

DuPont said he is a big advocate of “medication-assisted treatment.” For instance, he considers patients on methadone, a synthetic alternative to heroin, to be in recovery, especially since methadone users are also more functional than heroin addicts. Methadone cannot be injected, and needs to be taken only once a day, unlike heroin.

Drug-free programs and medication-assisted treatment programs should not be at odds with one another, DuPont stressed.

Such conflict prevents greater success in getting patients to recovery, he said. Instead, drug-free programs should allow for medication and medication-assisted treatment programs should be followed up with recovery support.

- Kids, Drugs, and Prevention

DuPont said the larger goal of drug policy, beyond recovery, is prevention, or “for kids to grow up not using any addictive drugs.”

This is not an impossible goal, he said, noting that in 1983 only 3 percent of young people didn’t use the “gateway drugs” alcohol, nicotine, or marijuana. In 2018, that number had ballooned to 26 percent.

Health policy should promote recovery and “discourage recreational pharmacology,” DuPont said.

The current approach does not discourage recreational drug use because we as a society see “experimenting with drugs” as normal, when it isn’t, he said. At the same time, we don’t see “experimenting with not wearing a seat belt” as normal.

DuPont said that when it comes to marijuana, nicotine, and alcohol, “we don’t articulate the standard” in the way we do with sugary sodas, seat belts, and helmets because not everybody follows the standard.

Society generally doesn’t begin to discourage recreational drug use before children reach their teenage years, he said, nor does it explain to children and adolescents the reasoning behind the discouragement.

“The vulnerability of the adolescent brain is unique,” DuPont said, noting it is particularly susceptible to forming addictions. “It’s not drug prevention only, it’s brain protection.”

DuPont noted that the worst thing a person can do is take a drug and discover that he or she likes it.

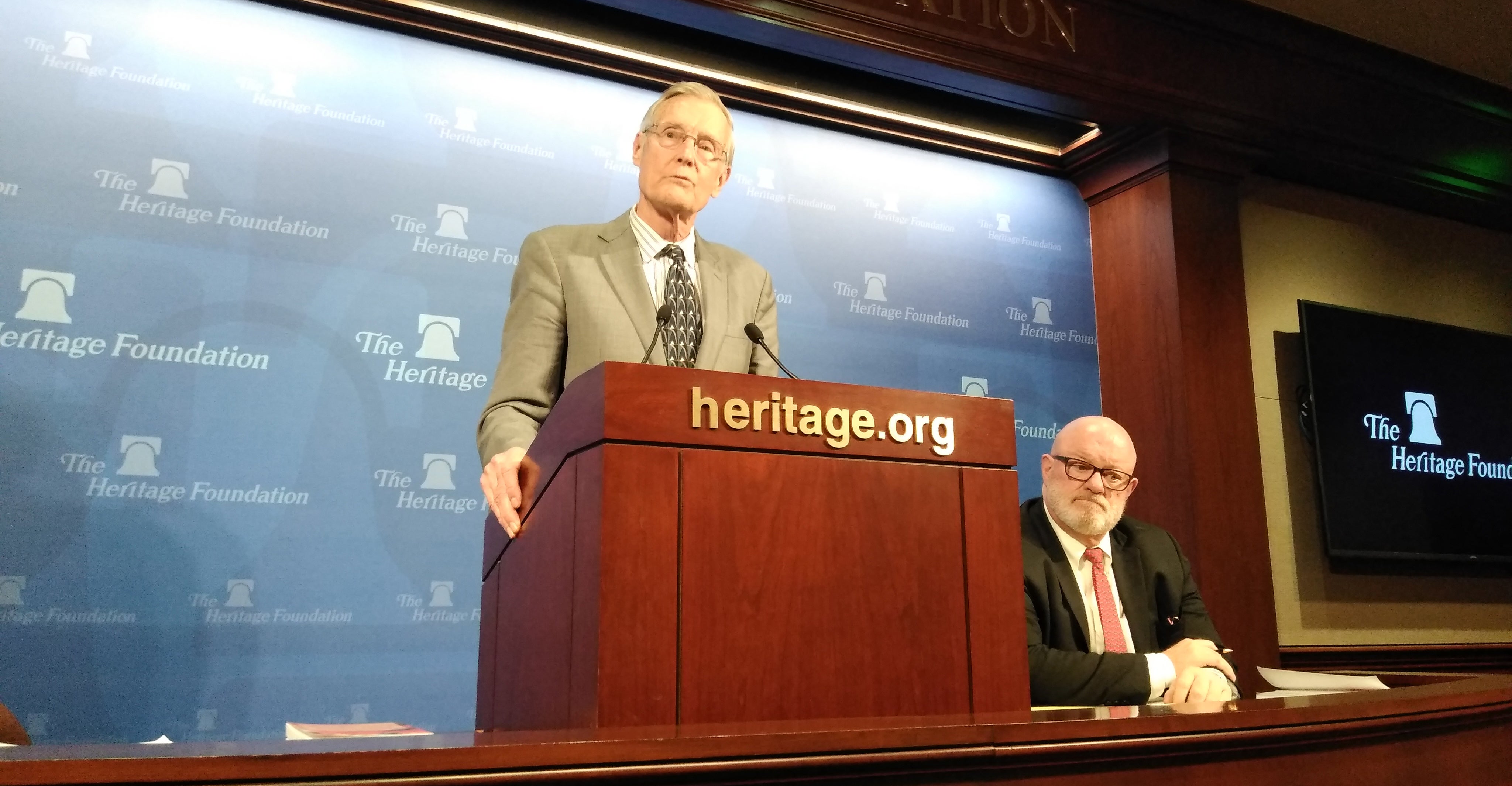

Robert L. DuPont speaks at The Heritage Foundation after being introduced by Paul Larkin, right). (Photo: Troy Worden/The Daily Signal)

- Public Health and Criminal Justice

DuPont said that “one of the stupidest things we do in corrections” is force people to pick between the criminal justice system and public health, when both should work together.

While the criminal justice system can work toward reducing the supply of drugs available for consumption, it must also be used as an “engine for recovery,” he said.

DuPont dismissed the idea that drug use has been overcriminalized in the justice system. He said some underlying offense other than drug possession usually exists and results in a drug user being sent to jail or prison.

Addiction is present in every field of medicine, DuPont emphasized.

Society should educate doctors and medical teams (which increasingly provide services) to understand that addiction is widespread and no case of addiction is hopeless.

“Many people in our field, I think, still do not understand … that it is possible that there are no hopeless addicts,” he said.

DuPont recommended that lifelong treatment be integrated into health care. He said doctors should ask their patients about addiction just as often as they ask about weight or diet.

Families, he said, often feel “overwhelmed” dealing with addiction and often don’t “get engaged with it” until it gets worse.

Doctors should work to educate families about how to help an addict who is among them, DuPont said.

“They’ve got to engage with love to support recovery,” he said.

- Marijuana and the Present Moment

DuPont expressed skepticism as to the viability of using medical marijuana as a means of recovery from opioids. The more people use marijuana, he said, the more they use alcohol, opioids, and nicotine.

“All these are linked. They’re not alternatives,” he said.

DuPont said he also is suspicious of medical marijuana because of its lack of specificity. Medical marijuana prescriptions often are, unlike other medications, smoked, taken for nearly any ailment, lack a dosage, and come in many varieties, he said.

He referred to the billion-dollar legal marijuana industry as a “fantasy,” “total fraud,” and “stalking horse” for the pharmaceutical industry to expand under the false pretense of being a legitimate medical alternative to other drugs.

“The commercialization is crucial to the spread of the behavior,” he said, referring to the connection between marijuana and addiction.

“The policy should be discouraging use,” he said.

DuPont recommended that society treat marijuana like it has nicotine, because of the success of the decades-old campaign against smoking.