How Emergency Spending Has Exploded in Recent Years

Paul Winfree / Justin Bogie / Romina Boccia /

Over the next several weeks, Heritage Foundation experts will publish short articles on the budget and federal spending. The next 12 months are a critical time for adjusting the spending outlook. In the last spending agreement enacted in the spring of 2018, Congress intentionally designed the spending limits so that they will be broken or eliminated before September 2019. The statutory limit on the debt will threaten to bind lawmakers from borrowing more on the public credit sometime after March 1, 2019, and lawmakers will be tempted to irresponsibly waive the limit, again. And many in Congress have argued for eliminating the earmark moratorium along with any fiscal restraint. These articles will provide context for each of these issues and establish a plan for how conservatives in Congress should react to the upcoming fiscal challenges.

In the summer of 2011, Congress passed the Budget Control Act to restrain discretionary spending and notionally “pay for” a statutory increase in the debt limit by reducing future spending growth. The Budget Control Act sets limits on discretionary spending for defense and domestic programs, and the move reduced discretionary spending by $741 billion.

The law also created a bipartisan committee—the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction or the “Super Committee”—whose task was to come up with a plan to achieve at least another $1.5 trillion in net deficit reduction by December 2011.

The Super Committee was not able to produce such a plan, which triggered an automatic reduction in the caps of $1.2 trillion minus debt service—or about $990 billion between 2013 and 2021—with $68 billion coming out of mandatory spending programs.

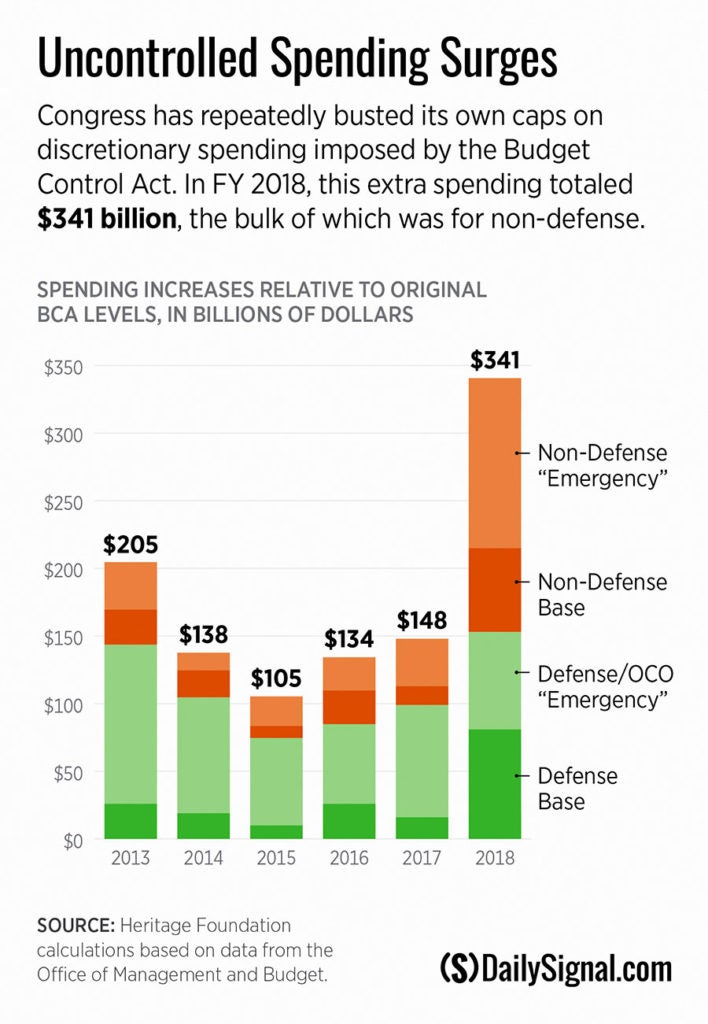

The Budget Control Act has proven to be just a speed bump on the road to fiscal crisis. It has done little to restrain the growth in mandatory programs that are driving the long-run unsustainability of budget, and Congress has repeatedly eroded the fiscal restraint imposed by the law by amending it to increase the discretionary limits and by designating new spending as an emergency, thereby evading any spending caps entirely.

It is now expected discretionary spending will grow $484 billion in the period of 2013 through 2019.

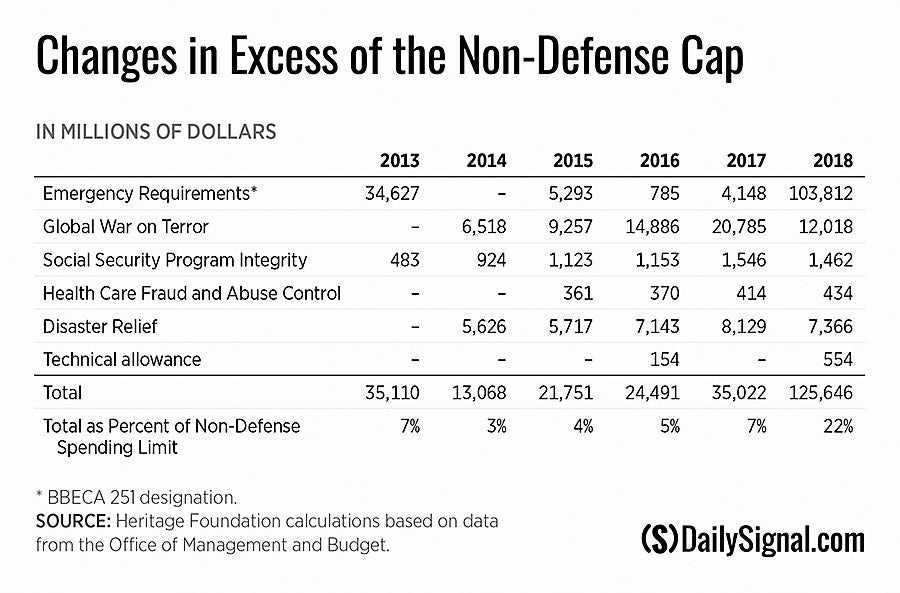

Since the beginning of the 115th Congress, domestic spending classified as an emergency has exploded from 5 percent of total domestic discretionary spending in 2016 to 22 percent in 2018.

That’s because appropriations rendered an emergency by Congress are exempt from both the discretionary spending limits and from the pay-as-you-go law that requires all new mandatory spending to be offset by other mandatory spending cuts or revenue increases.

There are three types of emergency designations Congress can use. Traditionally, emergency spending has included spending on wars, disasters, and other events that are unexpected, urgent, and not ongoing.

Since 2013, Congress also has authorized $255 billion in emergency spending on domestic programs (including disaster relief, domestic spending for the Global War on Terror, and program integrity measures) along with $481 billion in funding above the spending limits for national defense.

The fiscal benefit to emergency spending is that it is usually a one-time appropriation and does not necessarily establish a new status quo for spending and, thus, any further spending in this area will have to be justified again. And since agencies won’t lose the spending at the end of a fiscal year, they won’t rush to obligate it before the end of a fiscal year (similar to other discretionary appropriations).

But this has not been the case with some disaster-designated spending in recent history. Over the past five years, the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Disaster Relief Fund has received an average of more than $8 billion annually. Instead of being used sparingly to respond to unforeseen events, disaster funds are providing a yearly boost to the agency’s base budget.

The increases in discretionary spending are not the primary reason the country remains on an increasingly unsustainable budget path. Last year, discretionary spending accounted for less than one-third of the total federal budget and has generally grown with the economy over time.

The real problem lies with a subset of mandatory programs that grow on autopilot and that are designed to grow faster than the economy—Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid, and other health care programs. We will never grow or tax our way to budget sustainability given these large and expanding entitlements.

That said, discretionary spending is a good determinant of the size and scope of government. By continually increasing the resources available to agencies for general operations without fundamentally restructuring the government, Congress is simply contributing to a growing regulatory state by increasing those resources.

The spending limits must be extended and strengthened if we are to reduce the long-run regulatory burdens and general overreach of the federal government.

The graphics in this article have been changed and corrected, and a sentence was corrected to reflect that since 2013, Congress has authorized $255 billion in emergency spending on domestic programs.