A Lesson for NATO From Ukraine: In a War With Russia, Smartphones Might Be the Safest Way to Communicate

Nolan Peterson /

KYIV, Ukraine—After four years of constant combat against Russia and its separatist proxies in eastern Ukraine, Ukrainian troops have learned the value of creativity in warfare.

The battlefield innovations in technology and tactics that Ukrainian troops have made on the fly in eastern Ukraine reflect the sort of forward thinking, flexible mindset needed by NATO military officials to counter the Russian hybrid warfare threat.

For instance, the Ukrainians have sometimes used commercially available smartphone messaging apps as a primary means of military communication—especially in cases when combined Russian-separatist forces’ artillery has homed in on the Ukrainians’ radio signals.

“We mainly used encrypted walkie-talkies, but this was not reliable for very long,” said Alexey Kelt, a 23-year-old Ukrainian combat veteran of the war in eastern Ukraine. “There have been cases when the shells came after we talked on the encrypted radio.”

“To plan operations, we would sometimes communicate to each other using WhatsApp and Telegram,” Kelt added, referring to popular mobile messaging apps.

Ukrainian army veteran Yaroslav Sherstyuk, right, developer of the MilChat messaging app, makes a presentation to Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko, third from left, and other Ukrainian military officials. (Photo courtesy Yaroslav Sherstyuk)

Some Ukrainian troops, however, are wary about the security of commercially available messaging services. Recent reports, for example, have revealed that Facebook monitors what users send in private messages.

“Yes, unfortunately, our military uses all of the popular messengers presently, which I am very critical of—from Viber and WhatsApp to Facebook Messenger,” said Yaroslav Sherstyuk, a 31-year-old Ukrainian army combat veteran.

“In other words, all that is used while living in peace,” Sherstyuk said. “I am skeptical of all of them, since I admit that they may be under the control of enemy special services and could be used to work against us.”

A tech-savvy former Ukrainian artillery officer, Sherstyuk has created his own startup mobile app—MilChat—as a means of providing Ukrainian soldiers a free tool for encrypted military communication accessible on their smartphones.

“Today, most people in Ukraine are using foreign messengers,” Sherstyuk told The Daily Signal in an interview. “As a former military member and patriot of my country, I had a desire to change the situation. In addition, Ukraine is famous for its talented information technology developers.”

According to Sherstyuk, MilChat is now used by more than 3,000 active-duty Ukrainian soldiers—with about 80 new downloads daily.

“In the long run, I see one thing—all servicemen of the armed forces of Ukraine are simply obliged to use MilChat,” Sherstyuk said.

He added, “I recommend that MilChat be used by NATO forces.”

High Priorities

At least one NATO country is listening.

Maj. Ivo Zelinka, deputy commander of the Czech Republic army’s 43rd Airborne Battalion, said he believes smartphone messaging apps—such as WhatsApp and Telegram—are useful as a means of military communications in a potential conflict against Russia.

“With current smartphones, it is easy to send encrypted messages so well that U.S. or German security forces were not able to crack them,” Zelinka told The Daily Signal, referring to the use of those messaging apps by Islamic State militants, a tactic which stymied Western intelligence collection efforts.

“Add a little military R&D [research and development], and suddenly you have undetectable communications working everywhere, capable of sending classified messages,” Zelinka said.

Mobile messaging apps are particularly helpful for reconnaissance platoons that insert behind enemy lines for up to a week to collect intelligence regarding a military objective, and then safely communicate that information back to an operations center in friendly territory.

The MilChat messaging app is a free messaging app used by more than 3,000 active-duty Ukrainian soldiers. (Photo courtesy Yaroslav Sherstyuk)

On those kinds of missions, the use of military radios would be akin to shining a flashlight on a dark night, Zelinka explained.

“The very best U.S. [special operations forces] radio can safely hide the content of the message but not the fact that it was sent and your location,” Zelinka said.

Russian electronic warfare units continually sweep the battlefield to develop a baseline measure of the area’s normal background din of electromagnetic signals.

So, once combat begins, “if there is anything out of ordinary, they are able to detect it—it is mostly automatic,” Zelinka said, referring to Russia’s electronic warfare operations in Eastern Europe.

“You have to treat the electromagnetic spectrum as a visible spectrum and act accordingly,” Zelinka explained. “In the visible spectrum, a soldier looks around him and camouflages himself accordingly to resemble his surroundings.”

New Generation Warfare

Russia’s modern hybrid warfare doctrine combines the use of conventional military force with other nonkinetic means such as cyberattacks and propaganda to sow chaos and confusion among the enemy—both on the battlefield and deep behind the front lines.

Hybrid warfare is an evolving threat spanning every combat domain. Consequently, the U.S. military and its NATO allies have to be adaptive, not hamstrung by rigid battle plans, and able to anticipate threats before they manifest

Along that line of thinking, in 2017, the U.S. Army’s Asymmetric Warfare Group released the “Russian New Generation Warfare Handbook,” which used the war in Ukraine as a case study in preparing U.S. forces for a war against Russia.

With the Russian threat in mind, the Army report offered a blunt assessment of the U.S. military’s need to transform after focusing on counterinsurgency operations for nearly a generation.

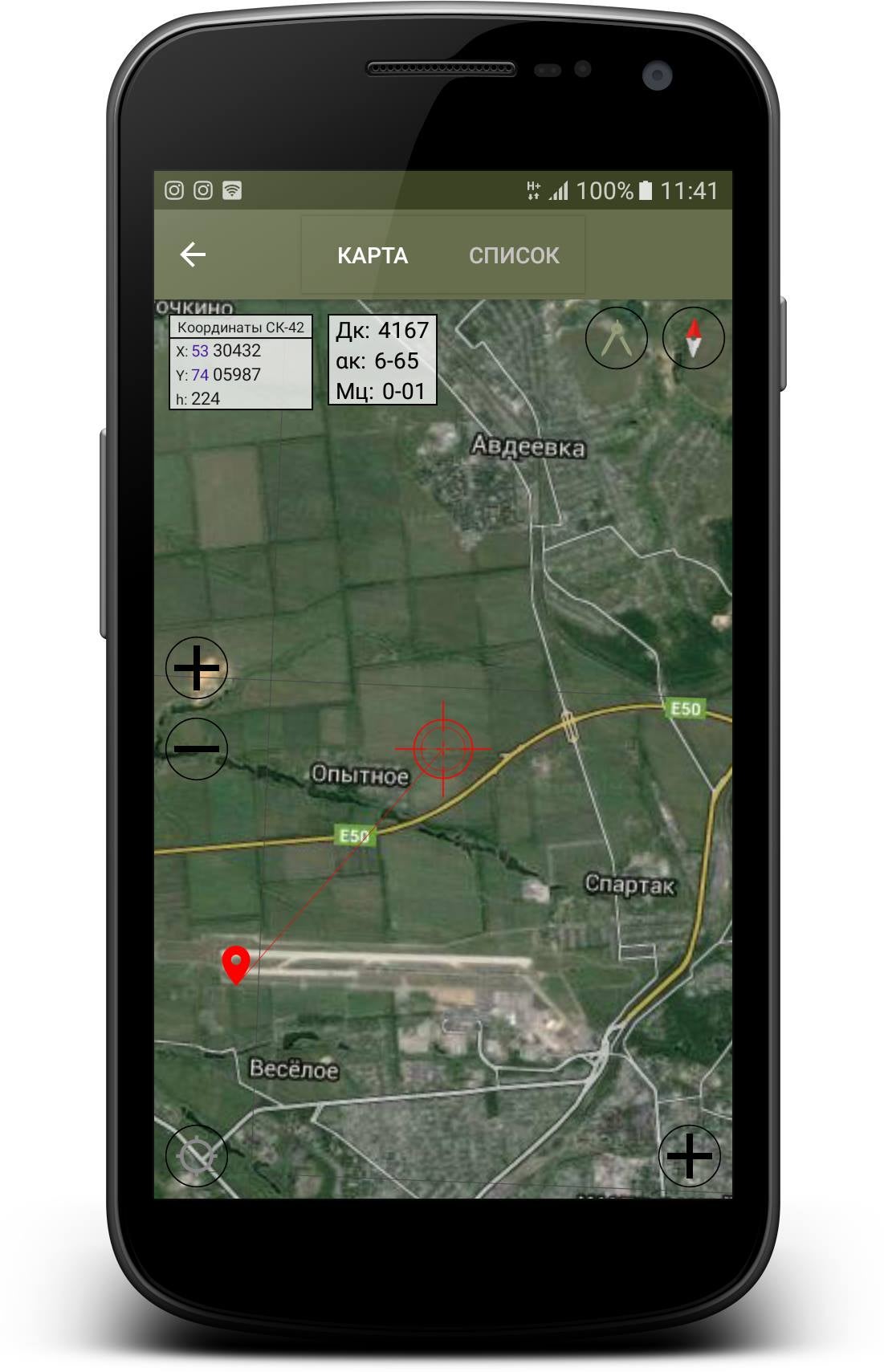

A screenshot of the MilChat messaging app, showcasing a overlay map of a battlefield. (Photo courtesy Yaroslav Sherstyuk)

In particular, the report took a hard look at the U.S. military’s dependence on high-tech communications tools, which could be vulnerable to Russian electronic warfare countermeasures.

“Russia has invested heavily in electronic warfare systems which are capable of shutting down communications and signals across a broad spectrum,” the Army report said. “The U.S. reliance on robust communication infrastructure and GPS navigation means that a sudden interruption of this capability, even for a short duration, can be disastrous to an operation.”

U.S. troops have some bad habits to kick after a generation of counterinsurgency operations, the report said. During counterinsurgency missions in Iraq and Afghanistan, for instance, U.S. troops often conducted “battle update briefs” to rear echelon command centers over the radio or a phone line.

“In a confrontation with Russians or their proxies, this type of action will get units targeted through electronic warfare and then killed with artillery,” the report said, adding that U.S. forces also need to practice better “radio discipline”—meaning shorter radio calls and other brevity tactics.

The 2017 Army report never overtly calls for the use of communications apps like MilChat. However, the report highlighted the need for U.S. troops to diversify their combat communications toolkit as a defense against a communications blackout by Russian electronic warfare units.

Thus, as a matter of battlefield survivability, the Army report called it a “high priority” for U.S. forces to learn how to “operate in degraded communications environments.”

“As next-generation Russian electronic warfare capabilities become more sophisticated and more prevalent on the battlefield, it becomes more important for commanders to both recognize the problem and prepare to continue operations in spite of communications problems,” the report said.

The MacGyver Doctrine

After four years, the war in eastern Ukraine’s embattled Donbas region has not ended. And neither has the battlefield school of hard knocks for Ukraine’s armed forces. Many technological challenges remain, including secure communications.

“Since the beginning of hostilities in eastern Ukraine, communication was and remains a big problem,” Sergey Bilous, a 41-year-old combat veteran of the war in the Donbas, told The Daily Signal.

“Good communication, this is a big percentage of success in any operation,” Bilous added. “So far we do not have that, but I really want to.”

At some places on the front lines, the Ukrainians have used runners to deliver handwritten notes. Hard landlines are mostly impractical. They’re susceptible to sabotage and too frequently damaged by mortars and artillery, Ukrainian soldiers say.

Ukrainian soldiers on the front lines peer across no man’s land. (Photo: Nolan Peterson/The Daily Signal)

Many Ukrainian units still use off-the-shelf, unencrypted walkie-talkies—the kind you can buy at any electronics shop. The walkie-talkies are reliable, but they have a key disadvantage—the enemy can hear everything the Ukrainian troops say.

In fact, over the open airwaves, Ukrainian soldiers and their enemies often trade insults and threats. To taunt their enemies, English-speaking Ukrainian soldiers sometimes go on the open airwaves pretending to be members of the U.S. Navy’s SEAL Team 6.

To offset their technological disadvantages, Ukrainian troops have adapted myriad, innovative ways to communicate with each other on the battlefield—including ad hoc code systems.

Sometimes, individual units develop their own unique code words tailored to the singular quirks of soldiers in the unit, as well as the features of the territory in which that unit operates.

Andrey Kobzar, a 43-year-old Ukrainian army veteran who served on the front lines in the Donbas from May 2014 to September 2015, explained:

We encrypted the locations, ammunition, weapons, time, and other necessary words with meanings known only to us. For example, we called one artillery position in the forest ‘bra,’ because on a tree there hung a bra since the pre-war times. Or the position we called ‘pig,’ because at the very beginning of our mission we saw a whole family of wild pigs in that place. There were other key concepts, known only to us. For example, the commander of our unit has a birthday on April 19. We used the number 19 as a basis for counting the time of day. For example, a phone call: ‘Take three liters of vodka and come to the pigs two days after the birthday.’ In translation: ‘Bring 300 high-explosive shells at 2100 to the position of ‘pig.’

Plan B

Ukrainian soldiers sometimes resort to cellphones for communication in the war zone, but usually only in a pinch. They understand that all cell networks in eastern Ukraine are under Russian surveillance.

“It was more difficult for the enemy to listen to our conversations through mobile phones” than over the open airwaves of unencrypted radios, “but the enemy could block this kind of communication,” said Oleh Kirashchuk, a 45-year-old Ukrainian army veteran of the war in the Donbas.

“If we have other types of safe communication—Viber, or WhatsApp, for example—then it will be extremely wonderful,” Kirashchuk said.

There are several limitations on the Ukrainians’ use of messaging apps in combat.

For one, the cellular networks in eastern Ukraine provide spotty data transmission reliability.

Also, in 2017, the average monthly salary of a Ukrainian soldier in the war zone was about $630, while a soldier in garrison received about $260 a month. Consequently, many Ukrainian soldiers can’t afford a smartphone. Instead, they use basic cellphones, which do not support messaging apps.

Yaroslav Sherstyuk, left, a Ukrainian army veteran and developer of the MilChat messaging app, with Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko. (Photo courtesy Yaroslav Sherstyuk)

Still, the Ukrainians generally prefer encrypted smartphone messaging apps over basic cellular text messages or phone calls.

“We’ve stuck to the American-made apps, sometimes we have used them to coordinate units on our flanks,” Ukrainian National Guard soldier Charitton Starsky told The Daily Signal.

He added: “For example, there was a case when an enemy reconnaissance unit was spotted far on our flank in the area of responsibility of another unit, and we used a messenger app to contact their commander and send him precise coordinates. But other than that, we mostly used conventional radio stations and codes, which I think were the safest way to transmit messages.”

“Yes, we used mobile applications for communication and information exchange—it helped a lot,” Bilous said, adding a cautionary note: “I think that you cannot trust such applications. There is no certainty that they are reliable enough to share information.”

Hard Knocks

Ukrainian troops have learned another hard lesson in eastern Ukraine—every type of electronic communication, encrypted or not, can invite enemy fire.

To target their artillery, mortars, and rockets, Russian forces in eastern Ukraine have the ability to home in on Ukrainians’ radio transmissions and cellphone signals.

“Often, the shells came when we had a large number of mobile devices in one place,” said Kelt, the 23-year-old Ukrainian combat veteran, recounting his experiences on the front lines in eastern Ukraine.

After four years of war, Ukrainian soldiers are still hunkered down in trenches and in embattled villages along a 280-mile-long front line (roughly the same distance as from London to Paris) in Ukraine’s eastern Donbas region. There, roughly 60,000 Ukrainian troops face a force of about 35,000 pro-Russian separatists, foreign mercenaries, and Russian regulars.

Ukrainian soldiers say that Russian forces target their artillery on the Ukrainians’ radio and cellphone signals. (Photo: Nolan Peterson/The Daily Signal)

Since the February 2015 cease-fire, known as Minsk II, the war has been fixed along a static front line defined by trenches, forts, and a no man’s land that varies in width from a few kilometers in some places, and close enough in others for the opposing camps to shout insults at one another.

There are few civilians left in many places along the front lines.

For that reason, some Ukrainian troops say, congregated cellphone signals are an aberration in the baseline electromagnetic signal environment of the Donbas—and a dead giveaway for a gathered military unit.

The U.S. Army’s 2017 “Russian New Generation Warfare Handbook” echoed what many Ukrainian troops have reported from the battlefields in eastern Ukraine about the Russians’ ability to target an adversary based on its electronic signature.

“The Russian [electronic warfare] systems also possess the ability to perform direction finding of electromagnetic signals,” said the U.S. Army report. “The Russians have the ability to call accurate fire on enemy forces based on those electronic intercepts.”

“After a while, we realized that it’s better to not take phones to combat,” Kelt said.

Combat Ecosystem

The war in Ukraine has been a laboratory for the Ukrainians’ use of off-the-shelf, civilian technologies for military purposes. And a generation of young Ukrainians with a talent for information technology are leading the way.

“In the modern world, it is necessary to keep pace with new technologies. When it comes to the army, then go one step ahead. And in special cases, adapt the innovations to existing solutions,” said Sherstyuk, the Ukrainian combat veteran who created the MilChat messaging app.

Based at the Noosphere Engineering School in the Ukrainian city of Dnipro, Sherstyuk worked with a team of software developers for two years to create a smartphone application to automatically control artillery fire.

The mobile app is called ArtOS.

“In the past, when guiding artillery weapons, officers were forced to calculate the necessary parameters independently, and thanks to ArtOS, all calculations are not only done automatically, but are also transmitted directly to the gun,” Sherstyuk said.

Ukrainian troops in the field laud the ArtOS app. They say it significantly reduces the time delay between identifying a target and firing a weapon.

“This program accelerated the calculation of coordinates for firing our artillery gun,” Kirashchuk said, adding that he had never before seen a smartphone used in combat operations.

“Around the autumn of 2014, I—like many others—first learned about the artillery officer Yaroslav Sherstyuk,” Kobzar said. “This enthusiast was the author of the first applied programs for smartphones in combat.”

A Revolution

MilChat is an encrypted messaging app. It uses all available internet connections, including cellular networks, and can also connect via Bluetooth to Motorola radios for transmission through encrypted channels.

Sherstyuk developed MilChat on his own to provide Ukrainian soldiers an easy to use, secure, and reliable means of communication in combat.

“If a serviceman uses MilChat, then he does not need to carry expensive equipment for communication—any mobile device with internet access or expanded secured military communication will fit,” Sherstyuk said.

“As for encryption,” Sherstyuk added, “we use end-to-end encryption in the Signal Protocol, which is the most secure method.”

On the front lines in eastern Ukraine, war has become a way of life. (Photo: Nolan Peterson/The Daily Signal)

The MilChat app also allows users to overlay tactical information useful to soldiers in the field. For example, the app includes a template for soldiers to report enemy activity according to NATO standards.

“We integrated mandatory elements for NATO soldiers like the SALUTE report,” Sherstyuk said. “MilChat directly structures the reports of a serviceman from the area of hostilities.”

SALUTE is an acronym that stands for Size, Activity, Location, Unit identification, Time, and Equipment—it is the U.S. armed forces’ standard format for reporting information about an enemy.

MilChat can also overlay data from other users on a smartphone-accessible map of the battlefield. “This tool will allow you to own a tactical environment without leaving the messenger,” Sherstyuk said.

Kobzar called Sherstyuk’s work a “revolution in military affairs” that has already saved the lives of many Ukrainian soldiers.

“The convenience, speed, and great possibilities of smartphone applications are now understood by absolutely everybody,” Kobzar said.

Speaking of Sherstyuk, Kobzar added, “This former officer deserves a monument of gold.”