In Updated Charts, How These 7 Taxpayers’ Bills Will Change If Tax Reform Is Signed Into Law

Rachel Greszler /

With lawmakers poised to pass the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act—a sweeping tax reform package—many individuals and families will see very different tax bills come 2018 and beyond. In general, an overwhelming majority of Americans will pay less in federal taxes.

So how will you fare under the GOP tax plan?

Well, on net, most Americans will see a significant tax cut, including virtually all lower- and middle-income workers and a majority of upper-income earners.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act will, on average, provide immediate tax cuts across all income groups, according to analysis from Congress’ Joint Committee on Taxation.

This analysis does not, however, show how those tax cuts would vary based on factors such as total income, type of income, number of children, and itemized deductions.

Among the new legislation’s most beneficial components is a significant reduction in business tax rates. This will help make America more competitive with the rest of the world, and will result in more and better jobs as well as higher incomes for American workers. The bill will also put more money back into the paychecks and pockets of most Americans.

The new bill does lack some important pro-growth and simplification components, however. It does not go far enough in eliminating deductions and loopholes or in reducing the top marginal tax rate. It adds a discrepancy between the top rate for individual versus pass-through and small businesses and adds some complicated business provisions. It also fails to eliminate the alternative minimum tax and it phases out and eliminates some tax cuts for budgetary reasons.

To get a better idea of how some workers, families, and small businesses will fare under the new tax code, The Heritage Foundation has estimated the tax bills of a range of taxpayers under current tax law and under the GOP’s final version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

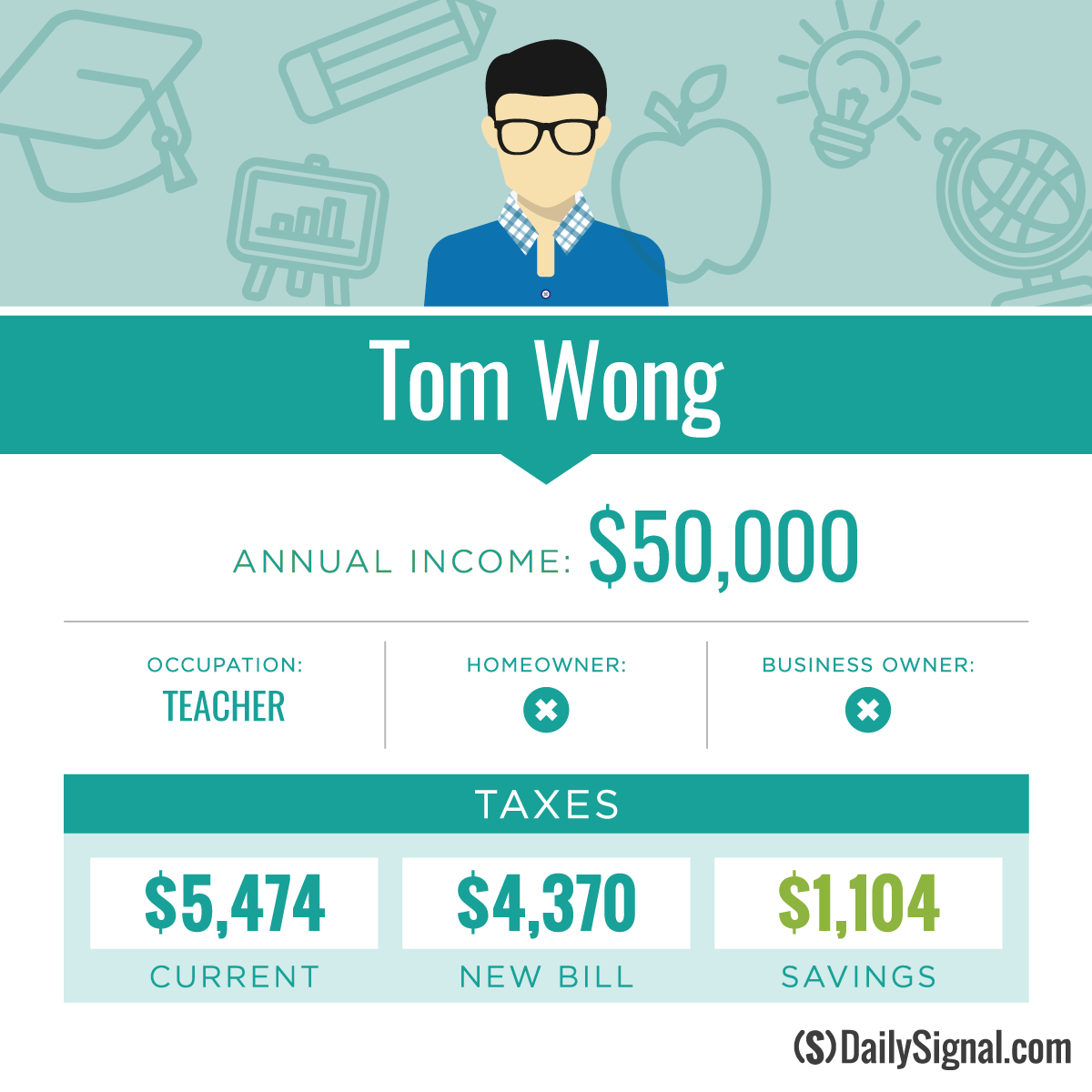

Tom Wong: Single teacher with median earnings of $50,000 per year. Under the current tax code, Tom pays $5,474 each year in federal income taxes. His tax bill will decline by $1,104, or 20 percent, to $4,370 under the new legislation.

These tax cuts come primarily from a higher standard deduction of $12,000 and from lower marginal tax rates. Currently, Tom’s marginal tax rate is 25 percent. But under the new bill, his tax rate will be 12 percent.

John and Sarah Jones: Married couple with three children, homeowners, and $75,000 in annual income. John is a sales representative and earns an average of $55,000 a year. Sarah is a registered nurse. After having children, Sarah cut back to part-time work and she earns $20,000 a year. Under the current tax code, John and Sarah pay $1,753 each year in federal income taxes.

But under the new tax bill, their tax bill will decline by $2,014, or 115 percent, to $0, plus a refundable credit of $261.

Even though John and Sarah would have more taxable income under the proposed plans (as a result of not being able to claim personal exemptions), they would still receive a tax cut because they would face lower marginal tax rates and receive larger child tax credits.

Their current marginal tax rate will decline from 15 percent to 12 percent, while their $3,000 in total child tax credits will double to $6,000.

The numbers listed in the above example for John and Sarah’s current tax payments assume John and Sarah own a home and live in a state with average tax levels. Under the current tax code, if they did not own a home but instead rented, their federal tax bill would be higher ($2,375 instead of their current $1,753 tax bill).

This would mean that their subsequent tax cuts—as renters—would be larger—$2,636, or 111 percent. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act partially limits—by placing a $10,000 cap on state and local tax deductions—an inequity in the current tax code that provides bigger tax breaks to property owners, wealthy individuals, and people who live in high-tax states.

Under the new tax legislation, however, John and Sarah’s tax bill will be the same regardless of whether they own a home or rent because the larger standard deduction will mean they will not itemize in either case.

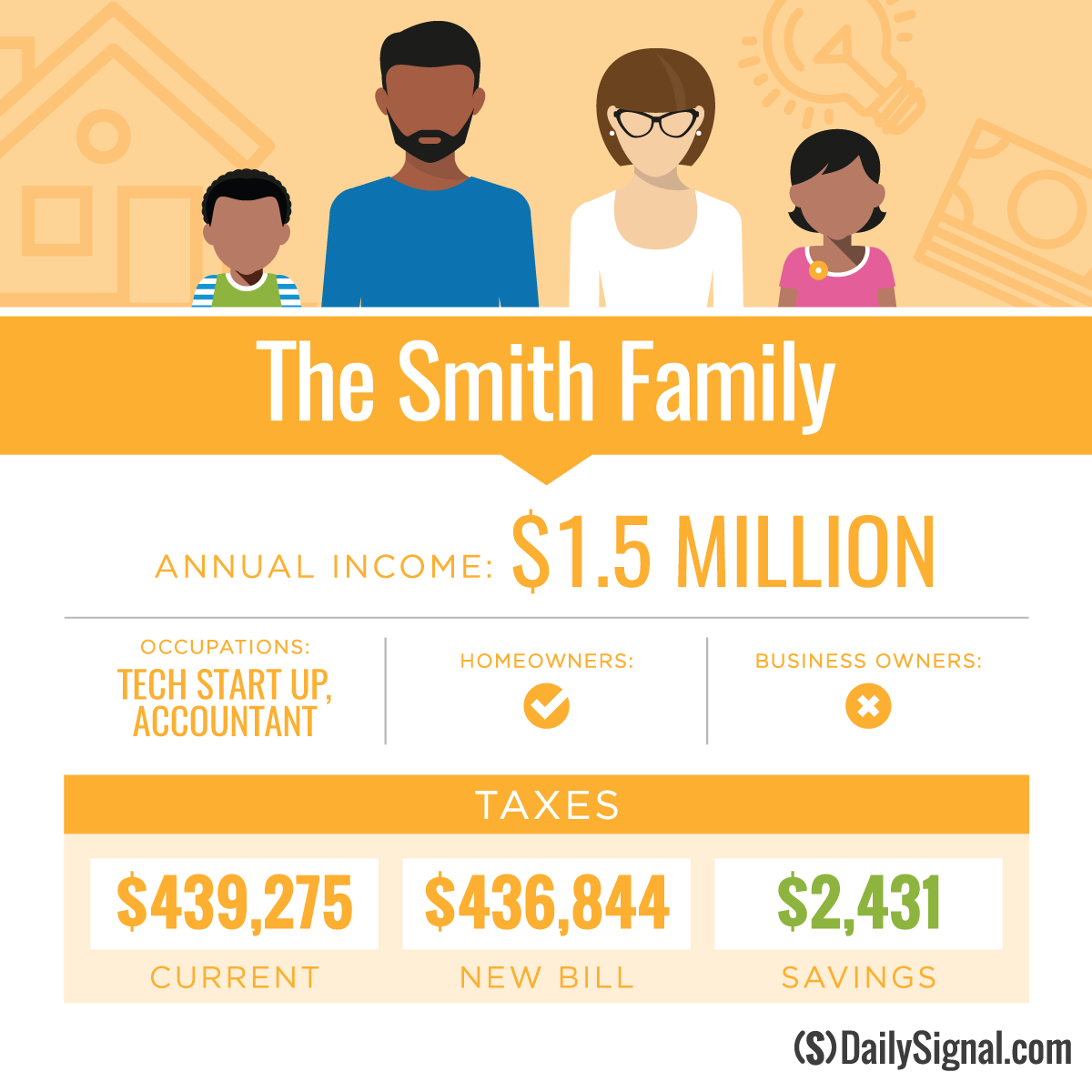

Peter and Paige Smith: Married couple with two children, homeowners, $1.5 million annual income. Peter works for a technology startup company and Paige is an accountant. Although Peter’s income fluctuates significantly from year-to-year, this was a big year for his company and he received a very large bonus, bringing his total earnings to $1.4 million. Paige’s stable income of $100,000 provided their family the financial stability they needed for Peter to take a risk and follow his dreams.

Under the current tax code, Pater and Paige pay $439,275 in federal income taxes. Their tax bill will decline slightly, by just $2,431, or 0.6 percent, to $436,8344 under the new tax legislation.

Peter and Paige’s taxable income will be higher under the new bill because they will lose most of their state and local tax deductions. Their total exemptions and child tax credits will remain the same—at zero—as their income is too high to claim any exemptions or credits under the current code or the proposed plans. They will face a lower marginal tax rate, however.

Under the current tax code, Peter and Paige face a top marginal tax rate of 40.5 percent (39.6 percent, plus the 0.9 percent Obamacare surtax). Under the new tax bill, their marginal rate will fall to 37.9 percent (37 percent, plus the 0.9 percent Obamacare tax).

Those marginal tax rates do not include Social Security’s 12.4 percent and Medicare’s 2.9 percent payroll taxes, which can lead to extremely high combined marginal tax rates for second earners that are part of a high-income family like Peter and Paige. Because Paige makes less than Social Security current taxable maximum income of $128,400 (for 2018), her combined federal income and payroll tax rate is 55.8 percent under current law and will fall to 53.2 percent under the new legislation.

Although Peter and Paige will have about $100,000 more taxable income under the new bill because they can only deduct up to $10,000 of their state and local taxes, their lower top marginal tax rate will help eliminate some of the existing tax penalty they face on work and investment.

The above example assumes Peter and Paige live in a state with average taxes. Currently, however, their federal tax bill could be tens of thousands of dollars higher or lower, depending on whether they live in a state with higher- or lower-than-average taxes for them to write off. This is not the case under the new tax bill because it caps state and local tax deductions at $10,000 (and at their income level, they would likely claim that full amount in any state).

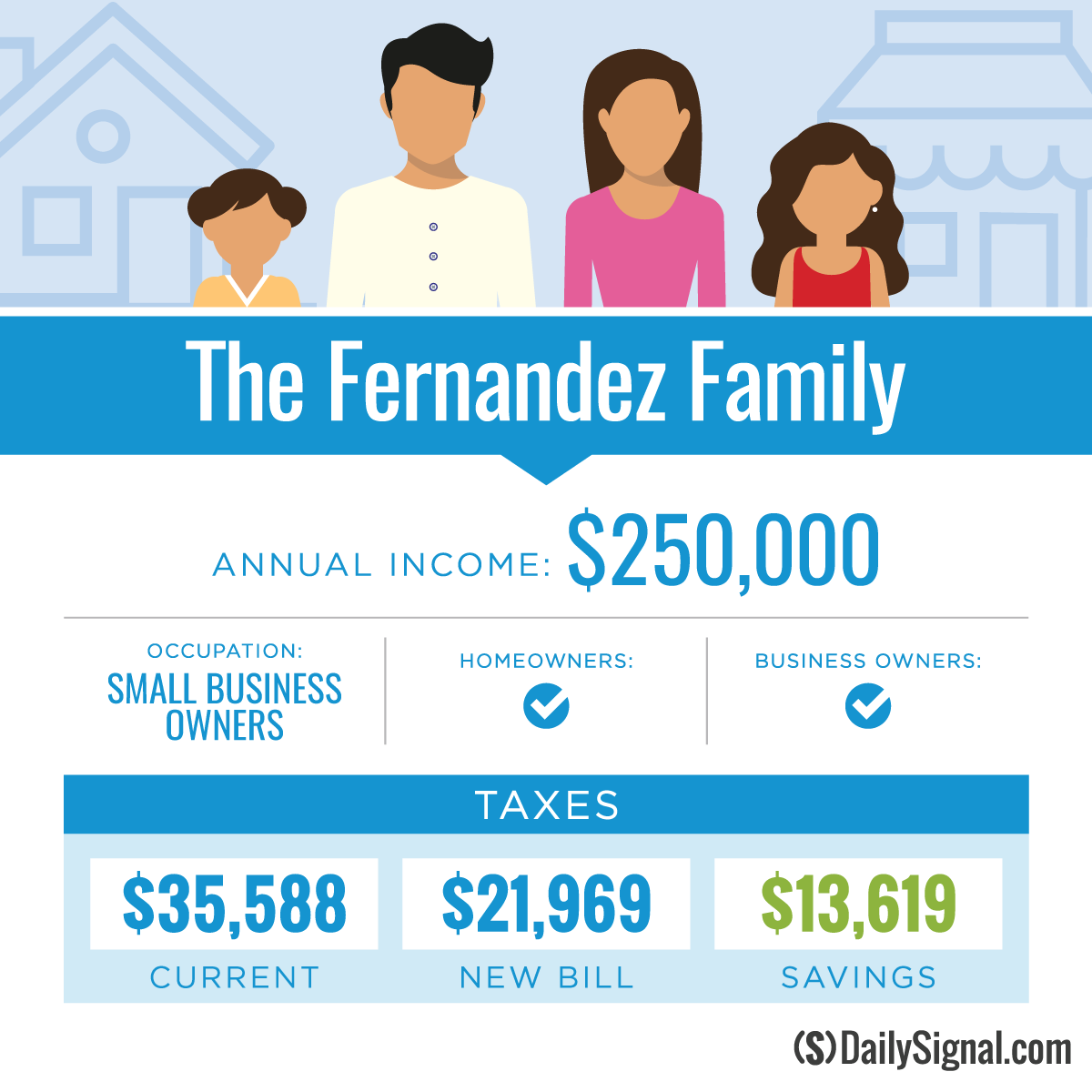

Jose and Marie Fernandez: Married couple with two children, owners of JM Blinds and Shades LLC, homeowners, $250,000 annual income. Jose owns and manages JM Blinds and Shades manufacturing company. Marie primarily stays home with their young children, but she also helps out significantly with the business when needed. Under the current tax code, Jose and Marie pay $35,588, which is their alternative minimum tax (AMT) amount.

The AMT is a separate tax system, created back in 1982 to make sure that millionaires paid their “fair share” in taxes. However, because the AMT was not indexed for inflation until 30 years after it was enacted, it now hits a significant number of middle- to upper-income Americans with a higher tax bill than they would otherwise pay. That’s because under the current tax code, taxpayers pay the larger of what they owe under the regular income tax system and the AMT.

The new tax bill increases the exemption level for the AMT, and significantly raises the income level at which the phase-out of that exemption begins (the phase-out creates a phantom, 35 percent marginal rate in addition to the AMT’s stated 26 and 28 percent rates.

Jose and Marie will still pay the AMT under the new tax legislation, but their AMT tax bill will decline by $13,619, or 38 percent, to $21,969.

Although the AMT is a separate tax system that does not include the new 20 percent deduction on small and pass-through business income, Jose and Marie still benefit—indirectly—from the deduction. Without the deduction, Jose and Marie would pay $32,039 in federal income taxes under the new bill—a smaller cut of $3,549, or 10 percent.

However, the deduction for their small business income lowers their regular income tax bill under the new bill to a level ($20,384) that is below their new AMT tax bill ($21,969). Thus, while they still pay the AMT (which does not provide the small business deduction), Jose and Marie would pay much more in federal income taxes without the deduction.

Jose and Marie’s marginal income tax rate is 35 percent under current law and will decline to 28 percent under the new legislation. The 28 percent is their AMT marginal rate (absent the AMT, their new marginal rate under the standard income tax would be 19.2 percent, which is 24 percent minus the 20 percent deduction).

Under current law, Jose and Marie make too much to claim the $1,000 per child tax credits. Under the new bill, however, they will receive the now-doubled $2,000 per child tax credits.

The above examples seek to show how some common taxpayers—including some wealthy individuals who are less common—would fare under the proposed tax reforms. Actual individuals’, families’, and businesses’ tax bills could vary significantly.

On net, however, most taxpayers—particularly lower- and middle-income taxpayers and businesses—will pay less in total taxes. Even more important than total taxes paid, however, is marginal tax rates. That’s because a lot of decisions are made at the margin.

For example, a worker is far more likely to work an additional hour if it counts as overtime and provides the equivalent of 1.5 hours’ worth of pay. And an individual is more likely to make a $1,000 contribution to his retirement savings account if that savings goes tax-free and means he can put all $1,000 away, instead of first having to pay between $100 and $400 in taxes on the savings.

Lower marginal tax rates are a big driver of economic growth, and the lower the rates, the higher the growth. The new tax legislation reduces the top marginal tax rate by 2.6 percentage points for individuals, and by as much as 10 percentage points for small and pass-through businesses.

While the proposed tax reforms do not achieve 100 percent of the potential pro-growth impacts that they could, they go a long way in helping to jump-start America’s struggling economy and put it on a pathway toward higher long-term growth. This leaves tax reform an unfinished business.

The expiration and phase-out of some of the tax cuts in this plan will provide the opportunity for Congress to enact more of the pro-growth components lawmakers left out of this tax package.