Senate Should Follow House’s Lead in Nixing Special-Interest Loopholes

Adam Michel /

President Donald Trump is right. Washington is a swamp, infested with special-interest groups feverishly working to keep their place in the capital bog.

Our current tax code is the leading example of institutionalized privilege—bought and paid for by lobbyists.

The tax code is riddled with privileges—special deductions for manufacturing, credits for everything from research to energy production to child care, and exemptions for medical costs, commuter expenses, and commercial development.

Tax reform should eliminate all these tax subsidies, which would allow for lower tax rates for everyone and full expensing. The result would be a fairer and more pro-growth tax code.

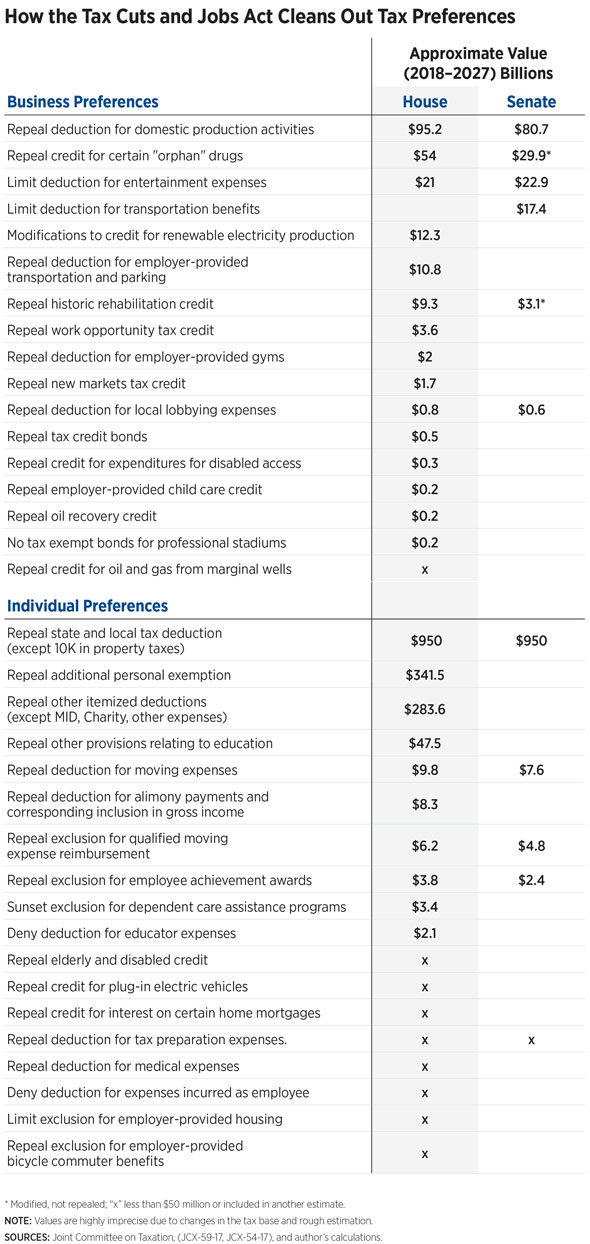

The House version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act would do a tremendous job of eliminating a large number of privileges in the tax code. The Senate proposal would also remove or limit several large subsidies, but would leave many existing loopholes targeted by the House intact.

As the conference committee works to reconcile the differences between the two versions of the bill, lawmakers should follow the House’s approach when considering which tax preferences to eliminate.

In the 10-year budget window, the House-proposed reforms include the repeal of almost $750 billion worth of tax carve-outs for both businesses and individuals. None of these were included in the Senate bill.

In the table below, each tax preference is listed with its estimated fiscal impact (where available) and whether or not each subsidy would be removed in the House and Senate tax plans.

Tax reform should eliminate as many subsidies as possible, and certainly not include any new or expanded special-interest handouts.

In addition to the reductions in subsidies included in the table, the House bill would expand three different energy credits: the energy investment credit, the residential energy efficient property credit, and the nuclear power credit. These three credits combined are valued at $36 billion over 10 years.

With a fiscal impact of $9 billion, the Senate bill would add a new credit to the tax code for employers who provide family and medical leave, and would expand the medical expense deduction—a health cost subsidy that the House tax plan would eliminate.

In addition to the tax preferences explicitly mentioned in the two tax reform bills, several other large preferences are left untouched.

The research and development tax credit and the low-income housing tax credit for corporations are valued at a combined $242 billion. The remaining deduction for up to $10,000 of individual property taxes is valued at $148 billion, the corporate deduction for state and local taxes is about $140 billion, and the exclusion for interest from municipal bonds clocks in at about $300 billion.

Many of these items are politically sensitive and are not included for elimination for political reasons. However, combined, the total value of the tax subsidies retained in the Senate version of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act is more than $1.5 trillion.

For those counting, that could equate to just shy of a 10 percent further reduction in individual tax rates—basically doubling the current individual tax cut in the Senate bill. It could also more than double the currently proposed corporate tax cut.

The conference committee should begin its work with the Senate-passed proposal because it improves on many of the House reforms. The committee should, however, defer to the House-passed bill when it comes to repealing special tax privileges.

The appropriate combination of the two versions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act can begin to drain the swamp and strengthen the pro-growth aspects of the legislation.