Trump Backs ‘Right to Try’ Experimental Drugs, Already Law in 37 States

Fred Lucas /

Laura McLinn’s son Jordan was diagnosed at age 4 with muscular dystrophy, a terminal illness with no cure. But, McLinn says, matters could be much worse.

“Both the president and vice president have expressed their support for ‘right to try,’” @VPPressSec says.

That’s because after the family tried for years, Jordan, now 8, qualifies for clinical trials for an experimental drug manufactured by NS Pharma.

However, that uncertainty led Jordan’s mom to become a public advocate for others with a terminal illness who are unable to try experimental drugs that haven’t won final approval from the Food and Drug Administration.

McLinn is among activists who support so-called “right to try” laws at the state and federal levels.

“Jordan is one of the lucky ones,” McLinn told The Daily Signal. “At one point he was too young for the clinical trials. Now we have friends who have children that are too old for the clinical trials. Without ‘right to try,’ for some there is no hope.”

So far, 37 states—red and blue—have passed some form of a “right to try” law, four of those just this year.

Still, McLinn and other advocates believe the FDA could step in to prevent states from implementing the laws and allowing sick patients to have access to drugs. So, she said, a federal law is needed to be proactive should the FDA seek to supercede state laws.

Legislation introduced in the House and Senate would make it easier for terminally ill patients to obtain experimental drugs, but still has some restrictions.

Existing state laws would apply only to drugs that successfully completed Phase 1 of the FDA’s approval process, but await final approval.

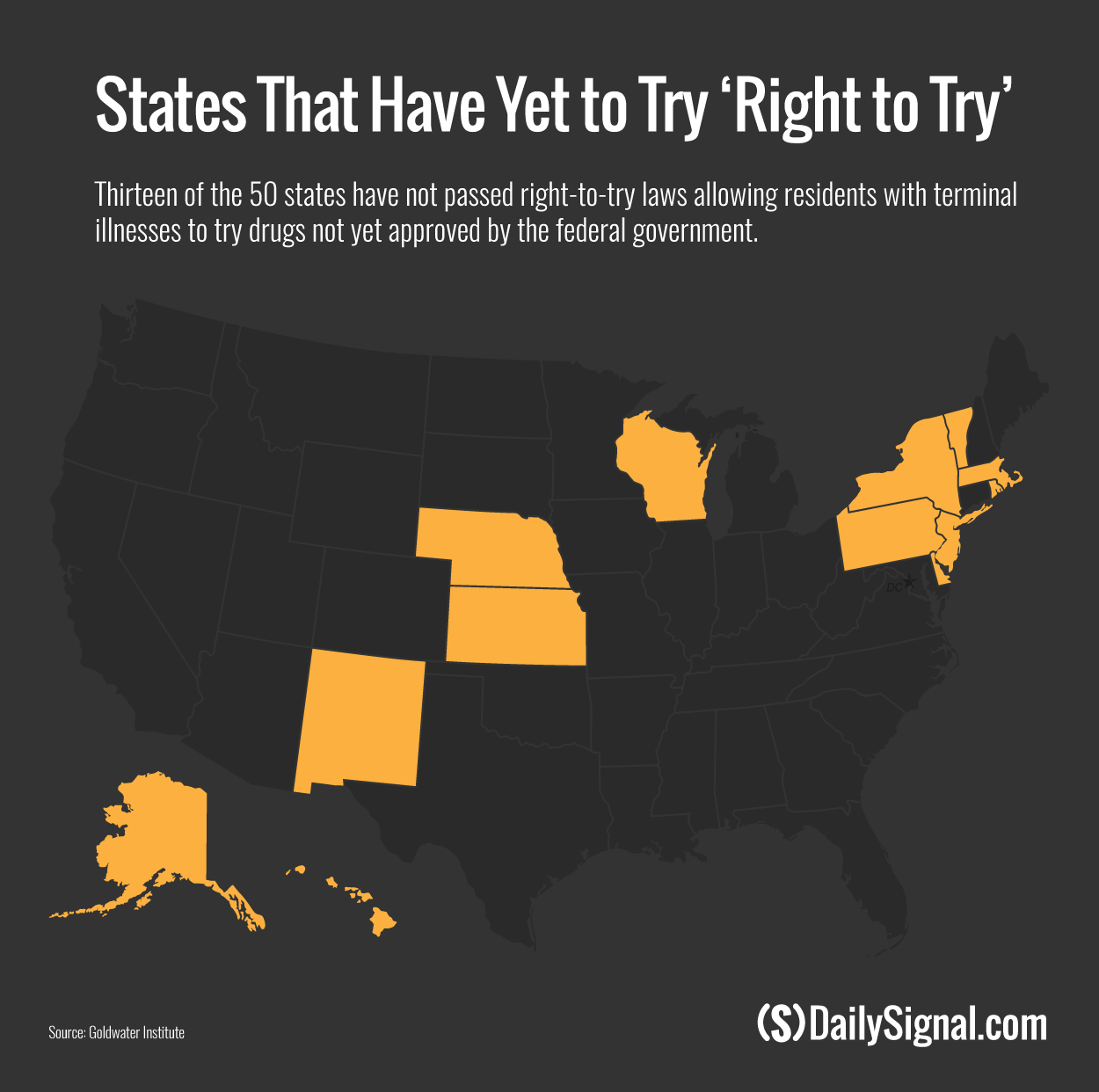

States that do not have right-to-try laws are Alaska, Delaware, Hawaii, Kansas, Massachusetts, Nebraska, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Wisconsin.

A Senate bill sponsored by Sen. Ron Johnson, R-Wis., has bipartisan support, with Sens. Joe Donnelly, D-Ind.; Joe Manchin, D-W.V.; Angus King, I-Maine; and 40 Republicans signed on as co-sponsors.

Reps. Brian Fitzpatrick, R-Pa., and Andy Biggs, R-Ariz., sponsored a companion bill in the House.

However, representatives of drug manufacturers and patient and physician advocacy groups say they have concerns about the state laws, according to a July report from the Government Accountability Office. The GAO report says:

Some contended that the laws would not help patients gain access to investigational drugs because they do not compel manufacturers to give access. As we previously noted, manufacturers have cited various reasons why they may not give a patient access to their investigational drug, and it is unclear to what extent these laws would address these concerns.

Others raised concerns that the laws might give patients false hope that experimental drugs will cure them. Thus, patients may not fully consider the risks associated with these drugs, which may not be effective and which could potentially be more harmful than no treatment.

Still, the Senate’s top health care priority remains deciding on repealing and replacing Obamacare, so it’s unlikely the right-to-try bill will move quickly at this point. But it does have the backing of the Trump administration.

Vice President Mike Pence, when he was Indiana’s governor, signed that state’s right-to-try legislation into law in 2015.

“Vice President Pence was proud to sign into law right-to-try legislation as governor of Indiana,” Pence spokesman Marc Lotter told The Daily Signal in an email. “Both the president and vice president have expressed their support for ‘right to try’ and are encouraged by current congressional efforts to help terminally ill patients try [to] access new medications.”

Pence met with the McLinn family in February.

“He restated his commitment to right to try and said President Trump is very supportive and told us, ‘Hope to see you at the signing [of the federal bill],’” McLinn said.

During his confirmation hearing, FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb told senators his approach would be to balance patients’ need to access drugs with the goal of thoroughly testing drugs to protect public safety. (Gottlieb grew up in New York, which is not a right-to-try state.)

In 2017 so far, four states have adopted right-to-try laws—Maryland, Iowa, Washington, and Kentucky.

In previous years, 33 other states adopted similar laws: Alabama, Arizona, Arkansas, California, Colorado, Connecticut, Florida, Georgia, Idaho, Illinois, Indiana, Louisiana, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, North Carolina, North Dakota, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Utah, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wyoming.

McLinn stresses that “right to try” should be a last resort when other options to obtain a drug or treatment aren’t available, such as clinical trials or a special FDA program.

According to the Goldwater Institute, many of the sickest individuals don’t qualify for clinical trials, with only 3 percent of cancer patients enrolled today.

The FDA already can grant permission through a “compassion use” waiver for some terminally ill patients who lack access to approved medicines.

However, right-to-try advocates say the FDA’s waiver program is time consuming for doctors and patients because the federal agency has a month to review and grant or deny the request. Additional questions can restart the monthlong process, the Goldwater Institute notes.

Under the state laws, a patient with a terminal illness is eligible to use experimental drugs only when conventional treatment options are exhausted and the doctor has advised use of such drugs that already passed the first phase of FDA’s approval process. The drug manufacturer also must approve the patient’s use of the experimental drug.

The matter isn’t as simple as right-to-try advocates contend, said Jonathan Agin, executive director for Max Cure Foundation, a nonprofit charity advancing research for pediatric cancers.

Agin’s daughter Alexis died from DIPG, an inoperable brain tumor, two weeks before her fifth birthday in 2011. So, he says, he identifies with other parents’ painful experiences but questions whether this proposal is the right patch.

“As a parent that desperately searched for something, anything to save my child, I truly believe that there is a middle ground that stops short of the right-to-try legislation, that stokes the fires of drug development rather than contracting it,” Agin told The Daily Signal in a statement.

Agin said he is concerned that right-to-try laws give parents the incorrect notion that open access to drugs will cure their child:

Of course, certain changes to the clinical trial system are necessary for pediatric cancer and other rare diseases and working on that component may in fact obviate some of the negative impacts of right-to-try laws, in my opinion. There are multiple spokes on the wheel that can and should be addressed.

The FDA doesn’t have a position on state right-to-try laws, agency spokeswoman Sandy Walsh said. However, Walsh defended the agency’s existing program for terminally ill patients.

“For over 20 years, the FDA has been committed to ensuring that the expanded access (often called ‘compassionate use’) program works well for patients and we have recently made significant improvements to its functioning and efficiency,” Walsh told The Daily Signal in a prepared statement, adding:

The FDA has authorized more than 99 percent of expanded access requests received in fiscal years 2010-2015. Emergency requests are usually granted immediately over the phone and non-emergencies are processed in a median of four days.

Access to investigational products requires the active cooperation of the treating physician, industry, and the FDA in order to be successful. In particular, the company developing the investigational product must be willing to provide it—the FDA cannot force a company to manufacture a product or to make a product available. Companies might have their own reasons to turn down requests for their investigational products, including their desire to maintain their clinical development program or simply because they have not produced enough of the product.

The Goldwater Institute contends that only about 1,000 people make it through the FDA’s “compassionate use” application process each year.

It notes that even then, a separate, unaffiliated committee called the Institutional Review Board must give final approval.

“And ultimately, it’s still an application to the government to ask permission to try to save your own life,” the Goldwater Institute argues on its website. “If you have a terminal illness, you don’t have time for a multistep government process. If your child is dying and you know there’s an investigational medication that is already helping other children survive, a shorter form isn’t good enough.”

“We need to remove barriers that limit doctors from providing the care they are trained to give—and this is exactly what ‘right to try’ does.”