A Liberal Democrat Student Explains Why He Advocates Free Speech at Colleges

Madison Laton / Diane Katz /

Free speech on campuses—and the lack thereof—was the topic of a hearing on Tuesday of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

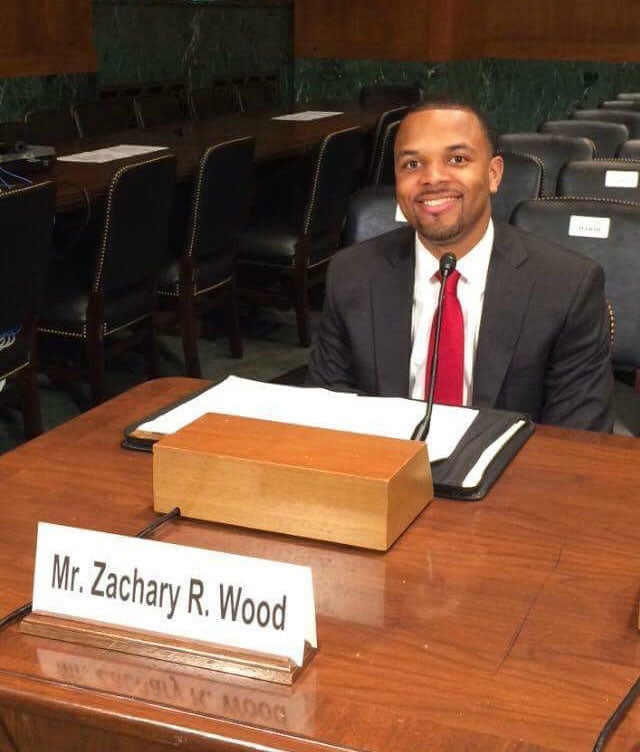

Among the panelists was Zachary Wood, a 21-year-old student at Williams College and president of a group called Uncomfortable Learning, which attempts to expose students to a diversity of opinion by hosting speakers on campus.

Zachary Wood promotes free and open speech at Williams College as president of the group Uncomfortable Learning. (Photo: Zachary Wood)

Opposition from administrators and students forced the cancelation of two speeches planned by the group this year. Wood, a self-described liberal Democrat, is a passionate advocate for free speech, and wise beyond his years.

Madison Laton, a member of The Heritage Foundation’s Young Leaders Program, interviewed Wood the day after the hearing about the search for civil discourse on campus.

Why did you get involved with Uncomfortable Learning?

I got a sense early on that there were certain subjects on campus that people were less inclined to want to discuss and debate simply because they were controversial. It wasn’t the case that people could debate things and disagree on things and work through their understandings of complicated issues without thinking, “This person is against me, or doesn’t like me.”

I thought that Uncomfortable Learning was important because it addressed the need to bring views to campus that people really weren’t engaging with, and those were largely conservative views.

While I identify as a liberal Democrat, and while I admire President [Barack] Obama and I agree with him on most things, there are times, there are circumstances in which I think what Republicans are saying not only needs to be heard, but has some insight and might even be right. Just because I’m a liberal Democrat, I don’t always agree with liberal Democrats.

How would you describe the political climate on your campus?

A lot of people are solidly to the left, but the most vocal factions on campus are not just left, they tend to be very radical. They don’t really believe in the political system. They don’t just think the right is wrong, they think that the left and right together are wholly inadequate and that what we need is a kind of socialist democracy. They’re Marxists, largely.

So the ones who constantly speak out on everything are far to the left, so it gives the impression that everyone is that far to the left.

Do those who oppose Uncomfortable Learning fairly represent the student body?

We have got a group of about 50 to 70 students who absolutely hate Uncomfortable Learning, and because they are so vocal, and because some are antagonistic—even using intimidation at times—it is difficult for people to come out and say, “I’m not that against this idea of Uncomfortable Learning, I’m at least willing to think about it more and try it out.”

And there is a number of people who are like, “I like UL but don’t tell anyone I said that.”

Why do you think so many of your generation are against free speech?

One thing at work is the echo chamber. You have a bunch of liberals in one place. The second part of it is that people have so much access to information, and so much of the news is opinionated and opinion-based.

Sites like Facebook that have algorithms make it easy for people to create a steady influx of things they want to hear. It makes it very easy for people to just say, “If there is a certain set of views that I don’t want to engage with, then I’m just not going to engage with them.” You can block anything or ignore anything.

>>> Read Sen. Chuck Grassley’s article, “Free Speech Is Dying on the College Campus. How We Can Revive It.”

I also think there is another element, and this is not discussed much: the trend on the left, in progressivism, to view inclusivity as a necessary component of moral progress. I have no problem with inclusivity, but in many respects this push for inclusivity often means restricting or constraining the rights of others, and that’s what I have a problem with.

College administrators and college educators are not encouraging students to see the world as a place with many layers of complexity, and a place in which you have to work through your differences and solve things and figure things out, not just push everything away and ignore it. So I think that my generation is less resilient than generations in the past.

Are students exposed to a variety of viewpoints in class?

No, with one caveat on that: I can name a few professors at Williams who do their very best to expose us to a variety of viewpoints. But outside of that, I do not think that people are exposed to a variety of viewpoints in class. It is often the case that professors have leftist views and they advance these views and they express these views as if that’s simply the way it is.

I try to give people the benefit of the doubt, not to assume that because of moral or political differences someone doesn’t have principles as well. Maybe they have insight into something that I could really benefit from.

What do you think are the consequences of barring speakers from campus?

Sen. Ted Cruz, R-Texas, touched on this [in the hearing], and I was glad he asked the question: “What happens when a heckler’s veto wins, when people can effectively shut down a speaker or prevent an event from happening?”

It allows them to see that as a victory when it should not be viewed as a victory. That is not what this country was founded on. That’s not what America’s about at our best. We are about empowering dissent. We are about saying, “Listen, you say what you think, you stand by your principles.”

>>> Why the Assault on Campus Free Speech Threatens Our Republic

When speakers are barred, what happens is that you have certain preconceptions, certain assumptions about how people see the world that do not get challenged in any way. You lose sight of individual differences. It subsumes individuality, and you don’t appreciate people for the uniqueness of their own perspectives. You lose sight of things like, Cruz and I disagree on a number of things, but when it comes to free speech, it sounds like we are pretty much in line with each other.

If colleges and universities are supposed to foster ideas, why do so many administrations cave to demands that undercut free speech?

It has to do with job security. It has to do with this idea of “no trouble on my watch.”

But my view is very different. I think that every issue that matters in this country is, in and of itself, controversial because people disagree. We shouldn’t be running from that on college campuses. We should be embracing that precisely because by embracing that we are deepening and advancing our own ability to construct stronger arguments.

That’s what college is really about. It’s about preparing us to be, whatever we’re going to be in the world, to make a positive difference in the world and to address any number of these issues that we really care about.

A lot of times, college administrators are trying to make students feel safe. But who is going to try to make you feel safe after you graduate? Is your employer going to say, “I want to make sure you feel safe today at work, so in this meeting, no one is to say anything”? That’s not how the world works.

At the hearing, Sen. Dianne Feinstein, D-Calif., said that the threat of violence should carry more weight than free speech in deciding whether to allow a speaker on campus. Do you think there is a point when security concerns should outweigh free speech?

I would agree with what Floyd Abrams and Frederick Lawrence said: We should always make the presumption in favor of free speech. That is to say, we should trust students, have faith in our students.

Let’s trust that if college administrators are doing our jobs correctly, students can handle this. If you really believe in the fact that your institution of higher education is a great institution, then you’ve got to have faith in your students.

>>> Conservatives Fight for Free Speech at a Far-Left College

Everyone needs to understand that part of liberty is the fact that I can’t force you to go to a talk you don’t want to go to. If it bothers you that much, don’t go. When I invite Suzanne Venker or John Derbyshire, you’re not mandated to attend. You’re not mandated to read their books. I think it would be great if you did, and I would encourage you to do so.

Administrators need to think about ways in which they can ensure that events are conducive environments for learning. If that requires more security, if that requires police, if that requires planning ahead, they need to take those steps. What they shouldn’t be doing is discouraging students from bringing controversial speakers.

You mentioned yesterday that you have tried to encourage your conservative classmates to speak up in class. What do you think it would take to convince them to do so?

The one thing that I’ve tried to do is when we’ve had panels, and everyone on the panel is liberal, if I have a friend who is a conservative, I’ll say: “This is an opportunity. They’re not grading you, they’re not someone from whom you may end up having to ask for a letter of recommendation. Try it here.”

The real fix would be for professors to encourage students to say what they think, to encourage them to speak up, to challenge them. I’d say that fewer than 20 percent of my professors, maybe 15 percent, say that.

How did you feel after the hearing? What do you think it accomplished, if anything?

I was encouraged by the fact that there was a general consensus that free speech is not just critical as this abstract value, but that people understand the concrete ways in which free speech is essential to our democracy, the concrete ways in which intellectual freedom on a college campus is indispensable to the kind of intellectual growth and development that is essential to becoming a more capable citizen in a very complex and competitive world.

I was emboldened by the fact that everyone on the panel, for the most part, seemed to agree that we’re oftentimes compromising speech and we need to push back against that.

Is there anything you would like to add?

I’ve received a lot of criticism and backlash, and I think it’s very easy sometimes for people to say that the problem is students—they are too sensitive or too intolerant.

I want to be clear about this: There is intolerance on college campuses, and the idea that you’re too weak or too frail or too sensitive is real. But it is on educators and administrators to think about the ways in which they can do more.

I think students mean well and administrators mean well, but I want to encourage people to not just blame student activists. Ultimately, we need to see this in terms of “What are the ways educators and administrators can do more to protect these values and promote political tolerance on campus?”