How a Delicate Alliance Defeated Nazi Germany

Lewis E. Lehrman /

It was President Franklin Roosevelt who decided on Dec. 31, 1941, that the allies should be called “United Nations” rather than “Associated Powers.”

Prime Minister Winston Churchill, anxious to please his American host, quickly agreed.

To name the alliance was easy. To sustain the alliance, through years of defeats until victory, required leadership and statecraft rarely exercised in the history of wartime alliances.

The prime minister admitted in 1942: “My whole system is founded on friendship with Roosevelt.” Two years later, just before D-Day, Churchill told Charles de Gaulle: “Each time I must choose between you and Roosevelt, I shall always choose Roosevelt.”

The prime minister did not neglect Josef Stalin, signing some communications with the Soviet dictator: “Your friend and war-time comrade.” But true comradeship with a cynical and aggressive Stalin at times proved impossible.

FDR maintained his faith that the personal relationships among Churchill, Stalin, and himself could make the alliance work.

In October 1944, the president wrote Stalin: “I am firmly convinced that the three of us, and only the three of us, can find the solution to the still unresolved questions.”

After World War II, Averell Harriman wrote that FDR had decided to establish “a close personal relationship with Stalin in wartime, to build confidence among the Kremlin leaders [so] that Russia, now an acknowledged major power, could trust the West.”

Roosevelt’s envoy wrote:

Churchill had a more pragmatic attitude. He too would have liked to build on wartime intimacy to achieve postwar understandings. But his mind concentrated on the settlement of specific political problems and spheres of influence. He despised Communism and all its works. He turned pessimistic about the future earlier than Roosevelt. And he foresaw much greater difficulties at the end of war.

In these judgments Churchill was the more prescient.

Stalin’s victories in the East gave him great confidence. Of the Allies, it was primarily Russian arms that destroyed the German army. The Anglo-American armies played an important but supporting role on the Western Front.

At sea, the U.S. Navy played the commanding role after 1942, the British navy the lesser role. The combined forces of the U.S. Navy, Marines, Army, and Air Force led to victory over Japan.

No matter these historic triumphs, the wartime alliance of America, the Soviet Union, and the United Kingdom could not keep the peace, the goal envisioned for the postwar United Nations.

Stalin himself declared, in 1945 at Yalta:

It is not so difficult to keep unity in time of war since there is a joint aim to defeat the common enemy, which is clear to everyone. The difficult task will come after the war when diverse interests tend to divide the Allies. It is our duty to see that our relations in peacetime are as strong as they have been in war.

Diplomacy requires patience and hard work, especially when cooperation turns to competition.

British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, and Soviet Premier Josef Stalin (left to right) met in Yalta, Crimea, only months before the end of World War II. (Photo: Pictures From History/Newscom)

None took the initiative and worked harder at those relationships than Churchill and Harry Hopkins.

“I came here as a representative of the president of the United States,” said Hopkins at the end of his second visit to Britain in July 1941. “His hatred for the things that [Adolf] Hitler stands for is the hatred of our people against tyranny.”

At the beginning of 1941, during the ABC talks among American, British, and Canadian military officials in Washington, it had been established that Europe and the Atlantic would be the primary military theater of the war.

Churchill continued to argue successfully for this priority. In June 1941, Hitler invaded the Soviet Union. Russia would join the Anglo-American alliance. Even the Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor did not alter that strategic decision—Europe first.

With that attack in December 1941, the Anglo-American alliance mobilized in the Pacific to defeat Japan. Four days after Pearl Harbor, Hitler declared war on the United States.

The truly global war would now engage the Allies against the Axis powers in the greatest armed conflict of history.

Hopkins proved himself indispensable in dealing with the Big Three leaders because, as FDR’s son observed, “Harry could disarm you. He could make you his friend in the first five minutes of a conversation and that must have been pretty rough with Stalin who was a tough old bird. … Harry had the ability to win him over.”

Russian Marshal Georgy Zhukov recalled meeting Hopkins in Berlin on his way back from Moscow in June 1945: “I had never met Hopkins, but according to Stalin, he was an outstanding personality. Hopkins had done a great deal to strengthen business contacts between the United States and the Soviet Union.”

He recalled Hopkins saying: “It’s a pity President Roosevelt didn’t live to see these days, it was easier with him.”

Roosevelt’s longtime aide maintained: “I respect Churchill, but he is a difficult person to get along with. The only man who found no difficulty in talking with him was Franklin Roosevelt.”

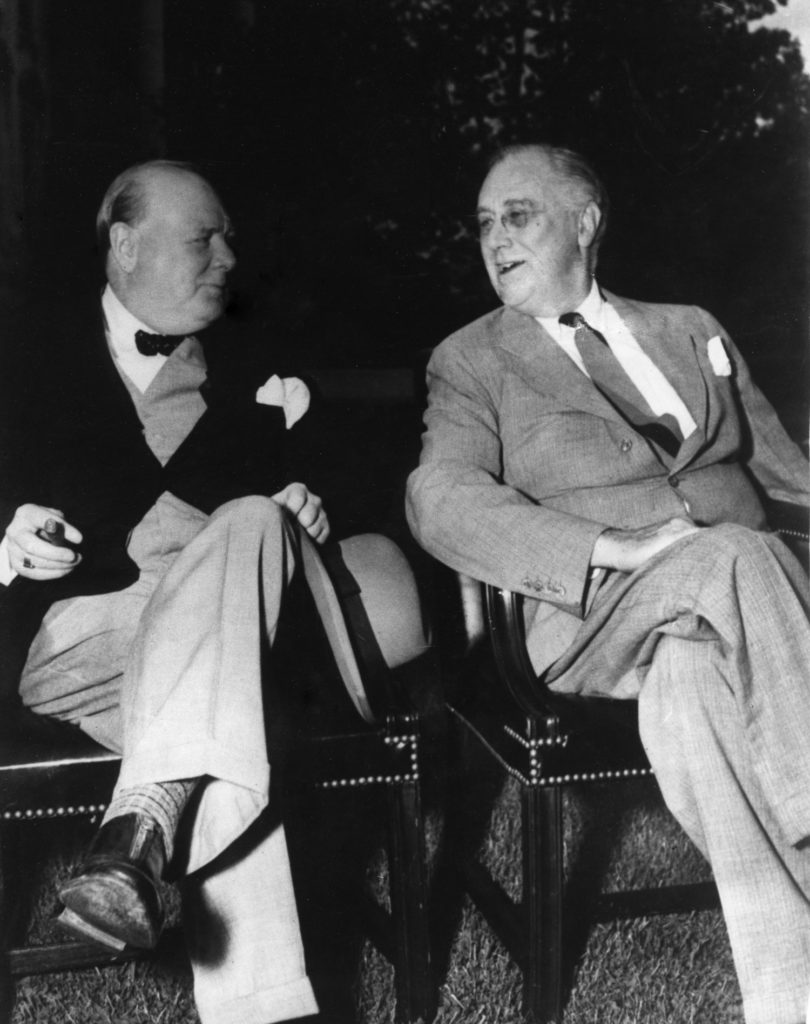

President Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Prime Minister Winston Churchill enjoyed a close and convivial friendship until Roosevelt’s death in April 1944. (Photo: Keystone Pictures USA/Zuma Press/Newscom)

The alliance would sustain unstinting diplomacy, negotiations, and compromise. There was little collaboration on the other side among the Axis powers.

In early December 1941, Russian, British, and American interests fused as German troops were repelled from the outskirts of Moscow, just days before the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor.

Churchill did forecast the ultimate victory of the Anglo-American-Russian alliance. Despite mistrust, spying, divergent national interests, the ground-sea-air alliance held together.

“No one could, alone, have brought about this result,” Gen. Ike Eisenhower told an elite London audience on June 12, 1945. “Had I possessed the military skill of a Marlborough, the wisdom of Solomon, the understanding of Lincoln, I still would have been helpless without the loyalty, the vision, the generosity of thousands upon thousands of British and Americans.”

“Some of them were my companions in the high command, many were enlisted men and junior officers carrying the fierce brunt of the battle, and many others were back in the U.S. and here in Great Britain, in London.”

“Moreover, back of us were always our great national war leaders and their civil and military staffs that supported and encouraged us through every trial, every test. The whole was one great team.”

Note: This excerpt was taken from Lewis E. Lehrman’s book, “Churchill, Roosevelt & Company: Studies in Character and Statecraft” (Stackpole Books, 2017).