He Was a Democrat for 30 Years. Why This Former Steelworker Now Backs Trump.

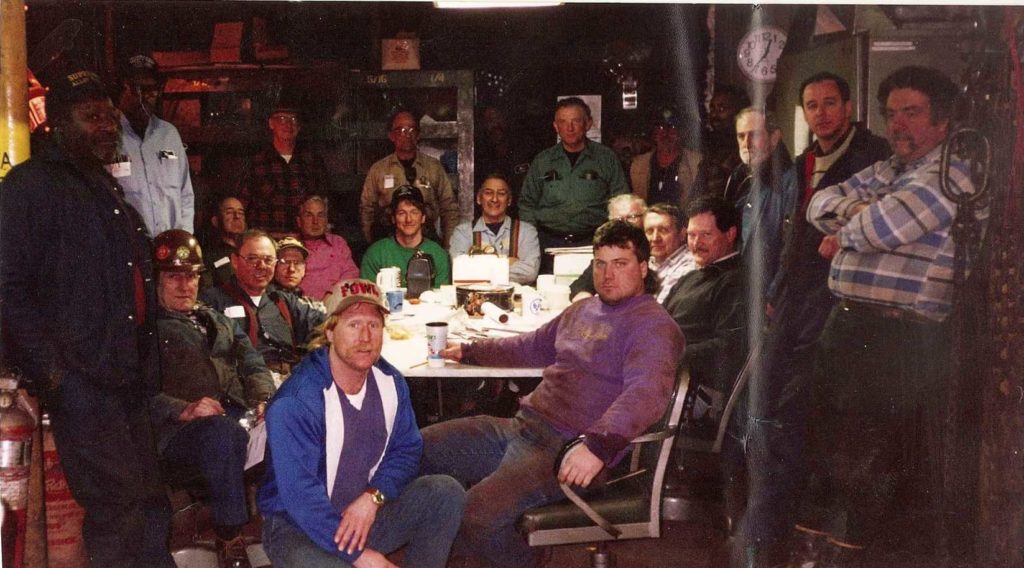

Morgan Walker /

For 17 years of his life, Roger Ramsey worked 80 hours a week as a maintenance technician for the Bethlehem Steel Company.

When the Sparrows Point, Maryland, steel mill closed, Ramsey was left wondering what the next step would be.

“I had spent 17 years of my life at that steel mill, and that’s when it hit me the most,” he told The Daily Signal.

“Everything that I had ever been promised—where if you work hard, you don’t screw up, then good things will come and in one fell swoop everything just slipped away—my mortgage, my kids’ college, it was all gone.”

Since Andrew Carnegie founded Carnegie Steel in 1892, steel has served as the backbone of the American manufacturing sector, but for many years the industry has been in a precipitous decline.

Bethlehem Steel was founded in 1857 and in 1916 purchased a steel plant at Sparrows Point, right outside of Baltimore. That facility quickly became not only Bethlehem Steel’s most productive mill, but the most productive one in the world. By the 1970s, Sparrows Point was the largest steel plant in the nation in size, personnel, and capacity.

But, as domestic steel became less prominent, the mill also took a hit. Sparrows Point’s first layoffs began in 1971, with nearly 3,000 people losing their jobs. In 1985, employment fell below 10,000 for the first time since the Great Depression.

Bethlehem Steel, once the nation’s largest steel company, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in 2001.

Various companies purchased the Sparrows Point mill from 2003 until 2012 when the mill officially closed its doors, leaving thousands of mill workers jobless.

“For months at a time I used to work 80 hours a week and that afforded me the ability to have my wife be a stay-at-home mom, to have good health care, to know I would be able to send my kids to college,” Ramsey said.

After being laid off from the steel mill, the financial stress took a toll on Ramsey’s family, and he was left with two major fears: “How am I going to pay for my mortgage and what am I going to do for health care?”

“For most people, those are the first two thoughts—‘We can’t pay our mortgage and we can’t afford to get sick,’” Ramsey said.

For the majority of his life, Ramsey relied on hard work, but when he was laid off, he was shaken.

“I always knew that as long as I just kept going into work and putting in the hours, that everything was gonna be OK, and all that got ripped away,” he said. “I just had to sit down and cry.”

“I also knew that no matter wherever else I got a job, more than likely, it was never gonna be as good as the steel mill. My life had basically peaked.”

After being laid off from Sparrows Point, Ramsey went to work as a maintenance technician at Domino Foods Inc. in Baltimore.

A Devastated Community

Since its closing in 2012, the town of Sparrows Point has yet to fully recover from the loss of the mill that served as the center of the local economy for over a century.

“Communities are usually devastated from the loss of a steel mill,” Ramsey said.

For years, the local diner thrived on visits from steelworkers and the local school relied on tax dollars to fund new playground equipment.

“Steelworkers make good money and they also pay a lot of taxes and that then goes to pay for teachers, fire departments, and playgrounds in the community,” he said. “So not only are you losing the steel mill, but the loss of that revenue alone is far-reaching too.”

“For every steel job, there are so many supporting jobs in outlying communities that it also affects,” Ramsey said.

After the mill closed, the town didn’t just lose thousands of jobs—it lost its identity.

“Sparrows Point has not recovered yet,” he said. “It will recover, but it’s never gonna be like it was before.”

“You’re never gonna have those high-paying blue-collar jobs again and that is a devastating thing in America,” Ramsey said.

Renewed Hope

According to an American Iron and Steel Institute report, U.S. steel imports are at an all-time high and exports are historically low. In 2015 alone, the U.S. steel industry imported more than it exported, with imports garnering 29 percent of the U.S. steel market—a record.

Nearly 1 million U.S. jobs are supported by the American steel industry, while the steel industry directly employs roughly 142,000 individuals, the American Iron and Steel Institute reported.

Even though the manufacturing industry is “not what it used to be,” Ramsey said he has a newfound hope.

On his fourth day in office, President Donald Trump issued a presidential memorandum calling for the construction of both the Keystone XL and Dakota Access pipelines. Congruently, he announced in a separate presidential memorandum that the nation’s pipelines, from that point on, will be built using American-made steel.

“We’re going to put a lot of … steelworkers back to work,” Trump said. “We’ll build our own pipelines, we will build our own pipes.”

On Friday, the State Department finally approved the construction of the Keystone XL pipeline.

Many steelworkers, like Ramsey, say this promise of domestic steel is a step in the right direction for America’s declining manufacturing industry.

“As far as manufacturing goes, we all know that the manufacturing industry is never gonna be what it was, and that’s OK,” Ramsey said. “One of the keys to reviving the manufacturing industry is energy, cheap energy. It comes from the shale boom, and that’s all steel pipe.”

“Hopefully we will use domestic steel for more than just the Dakota Access pipeline,” he said. “Using American-made steel on infrastructure will affect more than just steelworkers.”

The Dakota Access pipeline is a 1,170-mile oil pipeline project that will carry oil from North Dakota to an existing pipeline in Illinois.

Currently, the manufacturing industry accounts for only 9 percent of the U.S. labor force, which Ramsey once feared could continue to decrease.

Ramsey, who had been a registered Democrat for 30 years, said he voted for Trump because he represented “blue-collar folks” like him.

“Even though we’re just blue-collar folks, we’re not stupid, we know that companies have to keep their shareholders happy,” Ramsey said of the manufacturing industry.

“Sometimes, though, it has to be tempered a little bit by a corporate responsibility to the communities that they serve,” he continued. “The dedication should be a two-way street.”

Ramsey said he is hopeful that the Trump administration will serve middle America by reviving the manufacturing industry.

“I’m hoping that under President Trump, he can influence them to be dedicated to the communities that have served them so well for so long,” Ramsey said.