The Consequences of Immigration for America’s Public Schools

Steven Camarota /

It is difficult to overstate the impact that immigration is having on our nation’s schools.

In a recent report based on Census Bureau data authored by myself and colleagues Bryan Griffith and Karen Ziegler, we map the profound impact immigration has had on schools across the country.

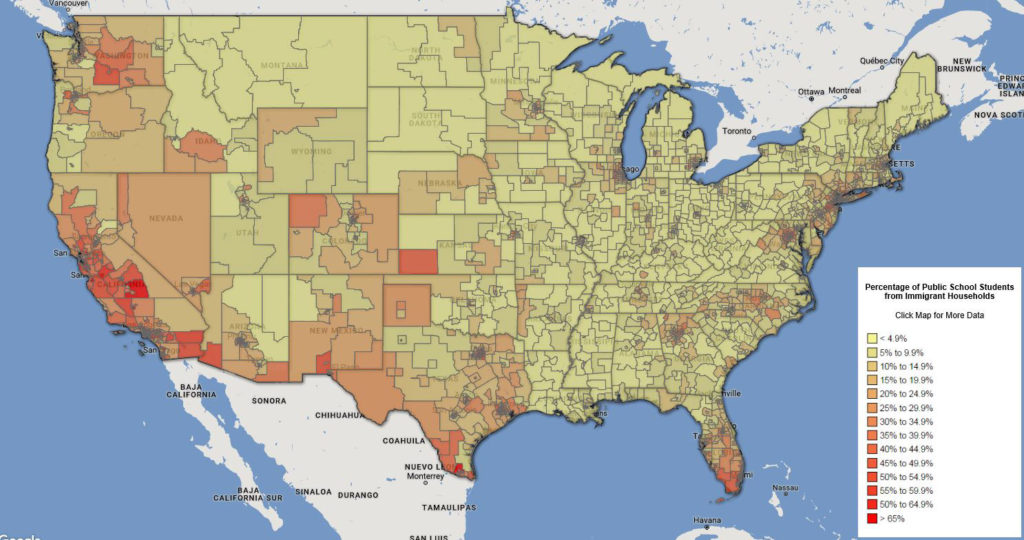

The red and orange shades highlight areas with a higher concentration of public school students from immigrant households. (Source: Center for Immigration Studies)

We find that nationally, nearly 1 in 4 students in public schools is now from an immigrant household (legal or illegal). The number of children from immigrant households in schools is now so high in some areas that it raises profound questions about assimilation.

What’s more, immigration has added enormously to the number of students who are in poverty or speak a foreign language.

All of this has occurred with little debate over the capacity of our schools to educate and integrate these students into our culture.

As recently as 1980, just 7 percent of public school students were from immigrant households, compared to 23 percent today.

High-immigration states have seen even more dramatic increases: 8 percent to 35 percent in Nevada, 11 percent to 34 percent in New Jersey, and 10 percent to 31 percent in Texas. Even in states that are not traditional immigrant destinations, such as Minnesota, Alaska, and Kansas, 1 in 7 students are now from an immigrant household.

As large as the growth at the state level is, the local impact can be astonishing.

The Census Bureau divides the country into Public Use Micro Areas, each containing roughly six to 10 high schools.

Immigrant households are very concentrated: Just 700 of the nation’s 2,351 Public Use Micro Areas account for two-thirds of students from immigrant households, but only one-third of the total public school enrollment.

There are many Public Use Micro Areas in which the overwhelming majority of students are from immigrant households—for example, 93 percent of students in North Central Hialeah City, Florida, are from immigrant households, as are 91 percent in the Jackson Heights and North Corona parts of New York City, 85 percent in the Westpark Tollway neighborhood of Houston, and 78 percent in Annandale, Virginia.

In the top 700 immigrant-heavy Public Use Micro Areas, one sending country typically predominates. On average, the top sending country accounts for 52 percent of students from immigrant households in these areas.

So not only do students from immigrant backgrounds often live in high-immigration areas, they often come from immigrant communities that are not very diverse.

Immigrant households also add disproportionately to the number of disadvantaged students.

In 2015, 30 percent of all students living below the poverty line were from immigrant households, making it unlikely that tax revenue grows correspondingly with enrollment in areas of high immigration.

Immigrants often settle in areas of high poverty, adding to the challenges for schools in these areas. In the 200 Public Use Micro Areas with the highest poverty rates in the country, where poverty among students averages 46 percent, nearly one-third of students are from immigrant households.

Immigration has also added enormously to the population of students who speak a foreign language. In 2015, nearly 1 in 5 students in the country spoke a language other than English at home.

>>>DC Council Teaches Illegal Immigrants How to Resist ICE

It is not just a simple matter of straining community resources. Perhaps the most important issue raised by these numbers is assimilation.

One way that assimilation works is that the predominance of natives and their children in a school, town, or neighborhood makes the absorption of American culture and identity almost inevitable among immigrants and their children.

If immigrants are a modest share of the local population, it makes identifying with America and its culture practically unavoidable.

But the level of immigration, most of it legal, has been so high in the last four decades that there are now whole sections of the country where U.S. natives and their children are actually the minority or nearly so. This may threaten assimilation.

Of course we need to provide education for children from immigrant households already in the country. Nearly 1 out of 4 children in public school is from an immigrant household, so how these children do is vitally important not only to them, but to the country’s future.

Moreover, the overwhelming majority of children in immigrant households were born in the United States, making them automatic U.S. citizens.

A key immigration policy question for our nation going forward is whether it makes sense to continue to admit 1 million legal permanent immigrants each year, and to tolerate widespread illegal immigration, without regard to the absorption capacity of our schools.

Arkansas Sen. Tom Cotton’s recent bill, for example—which would reduce the chain migration of family members and increase the share of legal immigrants who are selected based on skills—is a promising reform to consider.