Searching for the American Dream on the Edge of the War in Ukraine

Nolan Peterson /

SLOVIANSK, Ukraine—At the public library in this eastern Ukrainian city about 50 kilometers, or 30 miles, from the war’s front lines, a group of teenagers gather on a Monday afternoon to learn about life in America.

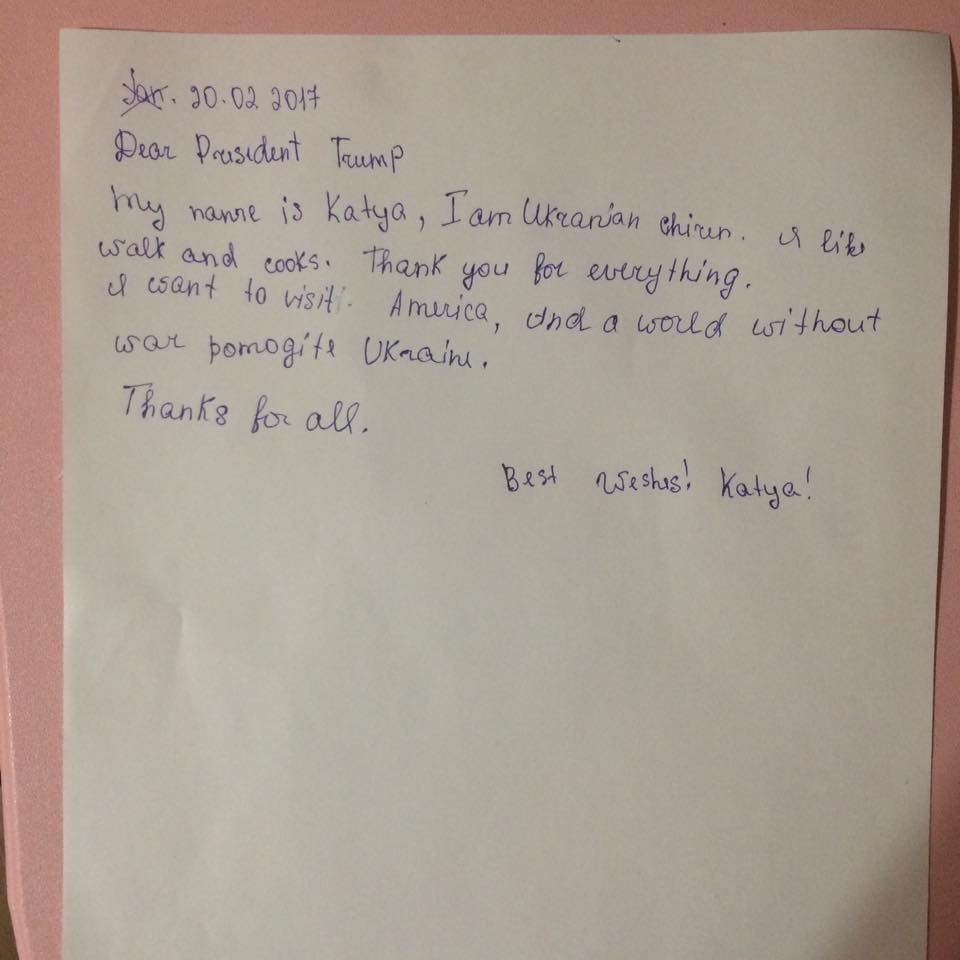

This is Presidents Day back in the United States, and, as a way to practice their English, the students write letters to U.S. President Donald Trump.

“Thank you for everything,” a student named Katya wrote to the president. “I want to visit America, and a world without war. Help Ukraine.”

On this day an ebullient volunteer named Oleseya leads the meeting—she asked that her last name not be used due to security concerns. Her energy and enthusiasm are boundless as she prompts the 22 teenage students through a series of icebreakers and English language exercises.

“I wish my children, Milena, 10, and Maria, 4, and all the kids in eastern Ukraine to forgive and forget the horrors they have seen,” Oleseya tells The Daily Signal. “They have supped their part of sorrows. It’s more than enough. And I am sure this generation is born to make a difference in Ukraine. They just have no other options.”

Oleseya, standing, leads the Access group through a series of English lessons and icebreakers. (Photos: Nolan Peterson/The Daily Signal)

The teenagers, who range in age from 13 to 15 years old, are members of a voluntary study group called Access in Sloviansk, which meets a few times a week to practice English and learn about American culture. Access in Sloviansk is one program among many at the Window on America center at the Sloviansk library. Participants in the center’s various programs range in age from 5 to 60.

At the library, an American flag hangs on the wall beside a poster of the Statue of Liberty and the New York City skyline. The shelves are lined with books about U.S. history and geography, as well as GRE prep books, U.S. college application guides, and a DVD collection of Rocky Balboa movies.

“The war affected everyone, but all people react and recover in different ways,” Darina Andrieieva, coordinator of the Window on America program in Sloviansk tells The Daily Signal.

“It’s not easy for everyone to quickly recover and move on, but I’m happy to see that many of the young people are looking forward to a better future,” Andrieieva says. “They are curious, they are learning with passion. And I’m happy to work in this center, because I have a great opportunity to encourage that passion.”

In April 2014, pro-Russian separatists, supported by Russian special forces and security agency operatives, took over Sloviansk. In July 2014, Ukrainian military units launched an operation to liberate the city of about 100,000 people. As artillery and tank shots rained down, and small arms gunfights broke out in the streets, Oleseya resolved that this cycle of violence that has consumed every generation of Ukrainians in living memory had to stop.

“On April 12, 2014, my little world changed forever,” Oleseya says, referring to the separatist takeover. “The war didn’t kill me, it made me more compassionate and every-moment-appreciating. Now, it’s my turn to help my neighbors—the university students, Access teenagers, Sloviansk locals—to be stronger, more encouraged, more loved, and more English-speaking.”

The 29 Window on America centers across Ukraine are a diplomatic outreach project organized by the U.S. Embassy to “promote mutual understanding between the United States and Ukraine,” according to a statement on the program’s website.

Yet, Sloviansk’s Window on America program was a true grassroots initiative launched by area residents. The Sloviansk center is actually a transplanted version of a Window on America program that existed in Donetsk before combined Russian-separatist forces took over that city in 2014. Today, Donetsk remains the capital of one of two breakaway separatist territories in eastern Ukraine.

“Not all of them dream about America,” Andrieieva says of the teenagers. “Some want to live in Australia, or Germany. But this center, and the desire to learn English, to learn something new, brings them all together. Especially for such a small town it’s a great cultural place.”

Back to Work

Later, at an industrial park on the outskirts of Sloviansk, Olexandr Ivanovich Poligenko opens the heavy metal door to one of his two crockery factories. Inside, on the factory floor the air is misted with clay particles spewing from machines operated by a pair of workers who hardly seem to notice as their boss enters the room.

An unformed tongue of gray clay oozes out of one machine like a giant worm. A worker uses a wire to slice the clay into bricks about the size of phone books. Soon, they will be shaped and then fired into fine ceramic crockery in one of two conveyor-belt kilns at another section of the factory.

On this night, the wide open, high ceilinged industrial workspace is loud with the sound of machinery and brightly lit. Normally, the windows are left open during the day to let some of the dust escape, Poligenko explains. But at night the workers prefer to wear face masks rather than let in the cold air. If you’ve ever experienced a Ukrainian winter, then you understand why.

Poligenko stands proudly, with arms folded, his shoulders pulled back, watching the fruits of 15 years of hard work in motion. His two factories in Sloviansk produce about 650,000 pieces of crockery a month. They also employ 260 people, including veterans and 22 Ukrainians who fled their homes due to the war. A planned third factory, the construction of which is nearing completion, will add another 150 jobs.

“My dream is to expand my business to America,” Poligenko says. “The war will be over soon, and we should look forward to the future.”

Clean shaven, with shortly cropped salt and pepper hair and round animated eyes, Poligenko is the director of Poligenko Trade Mark, one of the largest crockery producers in Ukraine.

Poligenko launched his enterprise 15 years ago. Today, it’s one of Sloviansk’s most important businesses. But success did not come easy. To build his company, Poligenko had to navigate Ukraine’s corruption-riddled, post-Soviet business-scape, replete with the nefarious influence of Mafia thugs, tribute-demanding oligarchs, and Russian agents. And there was the war, too, of course.

“It has become easier to do business in Ukraine since the revolution, but if the time of Yanukovych returns, I will not work,” Poligenko says, referring to the pro-Russian former president of Ukraine, Viktor Yanukovych, who was overthrown in 2014 by pro-European street protests.

Poligenko says he and his family have been forced to flee Sloviansk five times due to the war and various criminal threats against him. “I know what war is,” he says.

Albeit slowly, corruption is diminishing throughout Ukraine, as is the insidious Russian influence. The country’s economy is also slowly rebounding from the hit it took after the revolution and the loss of its Crimean Peninsula to Russia in 2014, and the three subsequent years of war.

Ukraine’s gross domestic product grew by a tepid 1 percent in 2016, and, according to various Ukrainian and international estimates, GDP is expected to grow by about 2.3 percent each year in the period from 2017 to 2019.

Poligenko is optimistic that Ukraine’s business environment is on the right trajectory and that the war will end soon, spurring him to look for ways to grow his business abroad.

With practically breathless enthusiasm, Poligenko explains how his ultimate dream is to build a factory in the U.S. But for now, he’s looking for a way to export his goods to the American market.

“We’re not looking for investors, we’re looking for business partners,” Poligenko says.

Role Models

In 2014, Sloviansk was at the epicenter of a separatist insurgency, which, with financial and military backing from Moscow, spawned two breakaway separatist republics in eastern Ukraine.

Ukrainian forces deployed to eastern Ukraine in the spring of 2014 to stop the combined Russian-separatist advance, which at that time was engulfing town after town across the Donbas, Ukraine’s embattled southeastern territory on the border with Russia.

Sloviansk fell to combined Russian-separatist forces in April 2014. According to accounts from civilians living in the city at the time, Russian special forces troops and agents from Russia’s security services were operating among the separatists. In the intervening years, however, the Kremlin has repeatedly denied supporting the separatists.

On July 5, 2014, after weeks of heavy fighting, Ukrainian forces retook control of Sloviansk. It wasn’t quite a Pyrrhic victory, but the battle to liberate the city left scars. Most notably in a nearby village called Semyonovka, which was practically leveled by artillery crossfire. Overall, about 100 people died in the fighting, and roughly 40 percent of the city’s residents fled.

In August 2014, one month after the battle, the carcass of a separatist tank destroyed by a landmine was strewn along a highway leading out of town. Buildings were pockmarked by bullet holes and artillery shrapnel. At an artillery-razed bus stop outside town, a woman and her child sat on their suitcases waiting for a ride. And in Semyonovka, residents who had fled the shelling trickled back, returning to the debris fields that used to be their homes.

Today, the city is peaceful, people have returned home and most of the physical damage has been repaired. The face of the city has also changed. Evidence of pro-Ukrainian sentiment is much more apparent than any latent pro-Russian leanings.

Statues of Soviet luminaries, including Vladimir Lenin, have come down. Ukraine’s blue and yellow flags are everywhere, as is the graffitied expression in Ukrainian, “Glory to Ukraine”—a patriotic rallying cry akin to “God Bless America.”

But the war isn’t over. Daily artillery and small arms skirmishes continue on the front lines about 30 miles away.

A cease-fire was signed in September 2014 in the Belarusian capital of Minsk, but it quickly collapsed. A subsequent deal struck in February 2015, called Minsk II, reduced the intensity of the war by proscribing airpower, as well as heavy weapons and armor within a certain buffer zone around the front lines.

However, the war never ended. Rather, it morphed into a static, indirect fire conflict, fought from trenches and improvised forts along a 250-mile-long front line.

A third of the 10,000 Ukrainians who have died in the war were killed after the February 2015 cease-fire was signed. Casualties, both civilian and military, still occur daily on both sides of the conflict. And about 1.7 million Ukrainians remain de facto refugees in their own country due to the war.

The fighting intermittently intensifies, as it did in the front-line town of Avdiivka in late January, briefly capturing international media attention. But the cease-fire has largely kept the war in check, and both sides have not made any major offensives in more than two years.

Hope

The Access in Sloviansk students kick off their Presidents Day meeting by singing a song in English.

They sit in a horseshoe formation of desks around this correspondent and his brother—who have been invited as guest speakers on this day. It is only the second time in two years that an American citizen has spoken at the Window on America program in Sloviansk.

At first, the young pupils are shy, yet effusively polite and well mannered. They raise their hands to be called upon before speaking. Most have smartphones in front of them, yet, demonstrating a level of politeness that escapes many American university students, the devices remain out of the students’ hands while anyone is speaking.

They do, however, whip out their phones to snap some selfies at the end of the afternoon. This correspondent and his brother happily oblige.

The author and his brother among the Access students at the Window on America center at the Sloviansk public library.

During an icebreaker session, when asked to name their favorite symbols of America, the teenagers’ answers span the gamut from the Thomas Jefferson Memorial in Washington, the city of Chicago, McDonald’s, Hollywood, baseball, and pizza (sorry, Italy).

When asked to name their favorite U.S. president, the students respond with answers like Abraham Lincoln, Ronald Reagan, and John F. Kennedy.

The conversation moves from the desks to a circle of beanbag chairs. The students warm to the Americans in their midst, and begin to open up. They talk about their hobbies, like playing soccer and guitar, and their favorite movies, which include “The Avengers” and “Home Alone.”

They have lots of questions about life in America.

“What kind of music do you like?” they ask. “What’s your favorite holiday? What sports do you play?”

Then, “Is it true you can live anywhere you want in America?”

In Ukraine, it remains a laborious bureaucratic process to officially change one’s city of residence. Ukrainians are still required to carry a domestic passport, a carryover from the Soviet era when authorities could demand to see one’s “papers” at any time.

Consequently, the fact that an American could pick up and move to any city of his or her choice, whenever he or she wants, is an alien concept.

Near the end of the meeting, Andrieieva, the Window on America coordinator, asks, “Can you explain for them what the American dream is?”

A brief pause to formulate a coherent response, a lot is riding on what comes next.

“It’s the belief that anything is possible, and that, no matter what, you always have the choice to make your life better,” this correspondent says. “No matter where you come from, or what your background is, you are in charge of your destiny.”

“Sounds amazing,” one young woman says, nodding approvingly.

“That’s the Ukrainian dream, too,” Oleseya, the volunteer group leader, chimes in. “You can do anything you want,” she says, scanning the faces of the teenage students. “Remember what I told you. You are a different generation. Your lives will be different.”

Work Ethic

Back in his office at the crockery factory, Poligenko leans forward with his elbows on his desk. “Believe in your work,” he says. “And everything is possible.”

The walls of Poligenko’s office are draped in military memorabilia—unit flags signed by soldiers, medals, shoulder patches, photos. Pieces of ammunition of various calibers line his desk. In a drawer he keeps a live grenade. “Just in case,” he says, smirking.

“Tea, coffee?” Poligenko asks at the beginning of the interview.

Minutes later his secretary appears with a tray of steaming hot cups of tea and coffee, as well as plates of chocolate candies, cookies, and pastries. Poligenko knows how to make a good impression.

Olexandr Ivanovich Poligenko’s blue and yellow coffee mugs—Ukraine’s national colors—have become ubiquitous throughout the war zone.

Poligenko is frenetically ambitious, constantly talking about plans to expand his business in America. With his teenage daughter and adult son chipping in to help with the Russian to English translations, Poligenko explains his idea of work ethic.

“If working from eight in the morning until six at night isn’t enough, then start at six,” he offers.

Poligenko talks about his business for a while, but his demeanor noticeably brightens when he speaks about the Ukrainian soldiers. He lauds the troops’ courage in combat, which he witnessed firsthand when they fought to liberate Sloviansk in 2014.

“The quieter the soldier, the more dangerous he is,” Poligenko says.

On his computer, Poligenko scrolls through photos from the various volunteer projects he has spearheaded to support Ukraine’s military. He has, over the course of the three-year-old war, traveled frequently to the front lines to deliver supplies, including military kit and food, as well as camouflaged storage containers used to conceal Ukrainian ammunition depots from Russian drones.

Poligenko also pays for the medals of soldiers who have received decorations for bravery but could not afford to buy the actual devices for their uniforms. “Who would help the soldiers if I don’t?” Poligenko says.

Poligenko is well-known for one unique item, which is now ubiquitous throughout the war zone.

At his ceramics factories, he produces a special blue and yellow coffee mug (Ukraine’s national colors) emblazoned with the national symbol, a trident, as well as the likeness of Ukraine’s traditional warrior, the mustached, fierce-looking Cossack.

“It’s a morale booster,” he says.

Ukraine’s military has dramatically improved, both in terms of supplies and fighting prowess, from the early days of the war in 2014 when its regular army was caught off guard by the combined Russian-separatist blitz across the Donbas.

With the regular army on its heels, Ukrainian volunteer military units stalled the separatist advance and turned the tide of the war in 2014. These paramilitary forces comprised civilians who often had little military training and were armed with hand-me-down weapons from area police forces. Yet, by July 2014, Ukraine’s mostly volunteer army had retaken 23 out of 36 districts captured by combined Russian-separatist forces.

The volunteer units have now been incorporated into Ukraine’s army and National Guard. And the volunteer troops who put their day jobs on hold to step forward and fight in the early days of the conflict are now some of the most experienced and battle-hardened soldiers in Ukraine’s military.

They also probably have more combat experience against tanks and artillery, and in trench warfare, than any group of active-duty soldiers in the world today.

“We have a real army now,” Poligenko says.

Ukrainians across all walks of life—from university students to businessmen—have volunteered their time and money, and sometimes risked their lives, to support their country’s war effort. Some decided to fight, others to collect and deliver supplies to the front lines.

The volunteers serve with no expectations of fame or fortune. They want to win the war so Ukraine can get back to the business of rebuilding itself into a functioning democracy free from Russian influence.

Olexandr Ivanovich Poligenko’s crockery factories employ 260 people, including veterans and 22 Ukrainians who fled their homes due to the war.

Perhaps the most remarkable thing about Ukraine’s grassroots war effort is that it materialized without governmental direction or backing. It was a truly spontaneous manifestation of Ukrainian society, underscoring a widespread attitude of self-reliance among Ukrainians who were unwilling to wait for the government to act in a moment of crisis.

Ukraine’s volunteer movement, consequently, is a sharp break from the Soviet mindset—a condition colloquially referred to as “homo sovieticus” among Ukrainians—in which people depend on the government for their financial stability and security, and are reluctant, either due to intimidation or apathy, to challenge the established order.

“It’s important for Ukrainians to help themselves, and not wait for the government,” Poligenko says. “Now, we have to finish the war and get back to work.”

Poligenko credits his business acumen and work ethic to reading books and a natural inner drive. He dropped out of university before finishing his degree, and his first job was repairing TVs. “I have no education,” he says. “I taught myself everything.”

“It seems like you’re living the American dream,” this correspondent says.

A pause as the sentence is translated. Then, Poligenko cracks a smile.

“It’s the Ukrainian dream now,” he says.