How Woodrow Wilson Planted the Seeds of the Administrative State

Steven F. Hayward /

Today the crisis of American government is expressed in an ungainly phrase that rarely appeared in conservative vocabulary in the 1950s and 1960s—the “administrative state,” by which is meant the independent “fourth branch of government” that fits nowhere within the scheme of the Constitution as understood by its authors.

Conservatives were slow to perceive the full nature and origins of the administrative state. They saw Marxism and radicalism as wholly foreign in character, and the character of Progressive Era and New Deal bureaucracy as primarily economic and narrowly constitutional in nature.

They missed the benign-sounding homegrown versions of deeply radical political philosophy behind the administrative state, and especially the key role of Woodrow Wilson and similar Progressive Era intellectuals. If Wilson was mentioned at all, it was usually with a shrug or mild approval of his conventional expressions of Christian faith.

The urgency of the Cold War dominated the attention of conservative intellectuals and activists alike, and with the predations of the New Deal fresh in mind, it was understandable that the conservatism of that time would set the New Deal as the horizon line for their attack on current American politics.

Only slowly did it come into focus that the New Deal was not the key turning point toward liberalism, and that socialism is not the chief threat to constitutional government and individual liberty.

The “administrative state” is not a new or recent phrase; it has been around for several decades, but its nature and depth was only recently more fully appreciated. Once confined chiefly to scholars and policy wonks, the term is now in widespread popular use.

The administrative state is not the same thing as bureaucracy, with its connotations of wastefulness, inefficiency, red-tape, and rule-bound rigidity, nor it is limited to the post-New Deal welfare and entitlement state.

Its character is best described by Alexis de Tocqueville in his famous chapter on “What Sort of Despotism Democratic Nations Have to Fear.” After struggling over what to call it, he could do no better than “soft despotism.”

The administrative state represents a new and pervasive form of rule, and a perversion of constitutional self-government. It has deep theoretical roots that were overlooked for a long time, roots inimical to the Constitution, thereby providing a lesson in the importance of understanding the principles of the Constitution.

A chief feature of the administrative state is its relentless centralization, but with a reciprocal effect: Its mandates, regulations, distorting funding mechanisms, and elitist professionalism have corrupted our political culture all the way back down to local government. It is the chief reason why Americans increasingly have contempt for government.

>>>Check out Steven F. Hayward’s book, “Patriotism Is Not Enough: Harry Jaffa, Walter Berns, and the Arguments That Redefined American Conservatism”

Unlike the attacks on the Constitution from Charles Beard, J. Allen Smith, Vernon Parrington, and other Progressive historians of the early 20th century that portrayed the Constitution as an anti-democratic fraud, the most potent part of Progressivism, and its chief legacy for today, was its theoretical attack on the American founding.

Progressivism reduced to the proposition that the principles of the founding were wrong for the 20th century, and needed to be discarded. The swirling currents of Darwinism, Hegelian historicism, and scientific hubris all combined, in the summation of Harvey Mansfield Jr., to make Wilson “the most powerful intellect in the movement” and “the first American president to criticize the Constitution.”

The Very Definition of Tyranny

What bothered Wilson the most was one of the central features of the logic of the Constitution as explained especially in The Federalist: the separation of powers.

Wilson laid out his criticism of the separation of powers in his book “Constitutional Government in the United States,” in which he argued in favor of a “Darwinian” constitution. Government, he argued, is not a machine, but a living, organic thing. And “[n]o living thing can have its organs offset against each other as checks, and survive. … You cannot compound a successful government out of antagonisms.”

Wilson thought the conditions of modern times demanded that government power be unified rather than fragmented and checked. His great confidence in the wisdom of science and benevolence of expert administrators led him to the view that the founders’ worries about concentrated power were obsolete.

He exhibited the combination of love for power and unbounded paternalism that is the hallmark of the administrative state today. He wrote in “Congressional Government” that “I cannot imagine power as a thing negative and not positive,” and on another occasion that “If I saw my way to it as a practical politician, I should be willing to go farther and superintend every man’s use of his chance.”

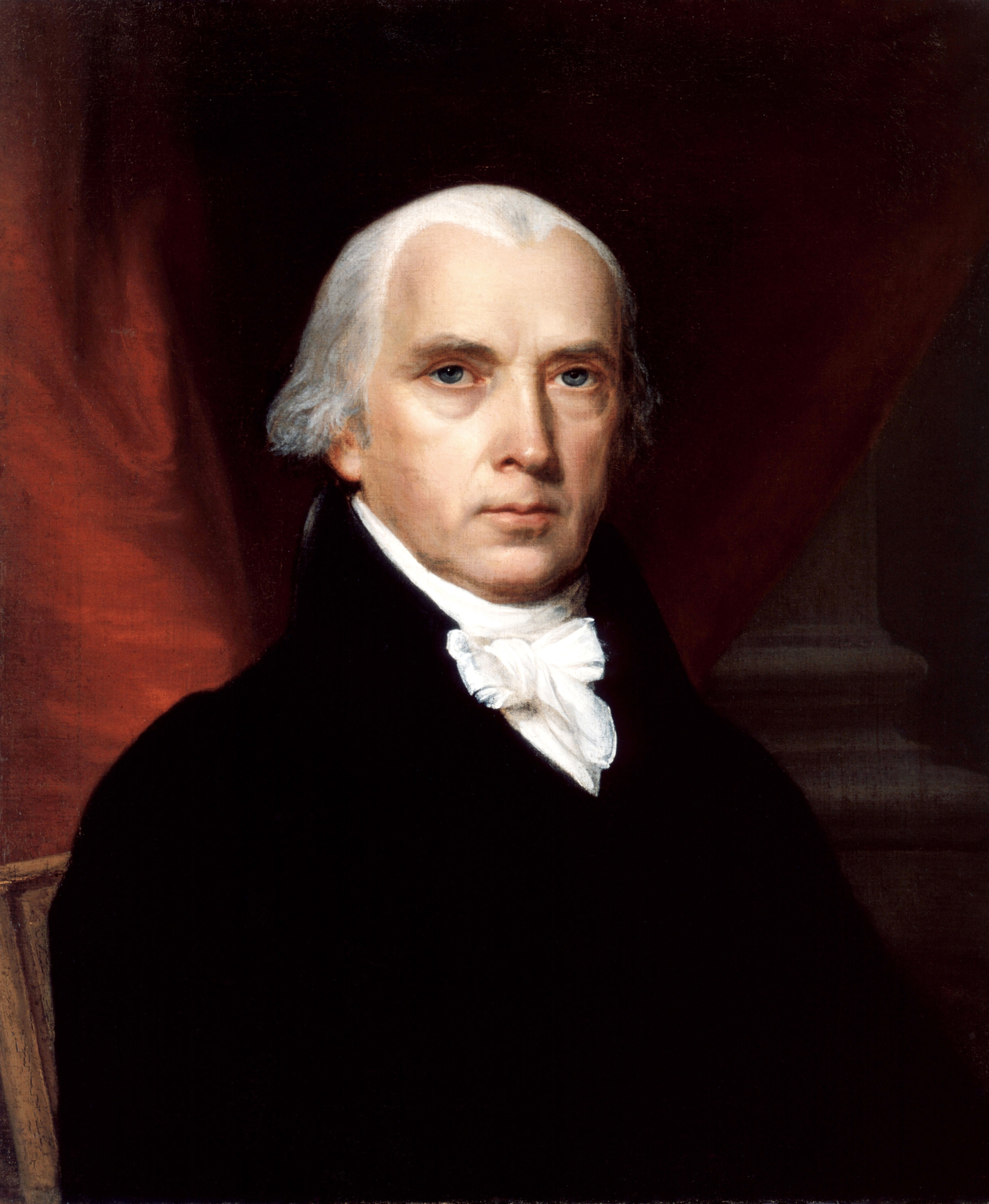

Quite a contrast from James Madison’s views expressed in The Federalist on the permanent reasons for suspicion of government power, as well as his specific understanding of the separation of powers: “The accumulation of all powers legislative, executive, and judiciary in the same hands, whether of one, a few or many, and whether hereditary, self-appointed, or elective, may justly be pronounced the very definition of tyranny.”

James Madison, a key American founder and author of the U.S. Constitution. (Photo: Pictures From History/Newscom)

Wilson explained once that the increased role of the national government could be accomplished “only by wresting the Constitution to strange and as yet unimagined uses. … As the life of the nation changes so must the interpretation of the document which contains it change, by a nice adjustment, determined, not by the original intention of those who drew the paper, but by the exigencies and the new aspects of life itself.”

The legal academy was happy to oblige. Harvard’s Roscoe Pound, for example, remarked that “No one will assert at present that the separation of powers is part of the legal order of nature or that it is essential to liberty.”

The main reason Progressives like Wilson no longer shared the older liberal suspicion of government power was the new view that politics and administration could be neatly and cleanly separated, with administration entrusted to scientifically trained and disinterested experts, who by their very expertise should be insulated from political pressure.

Frank Goodnow, a prominent political scientist of the Progressive Era and one of Wilson’s teachers, provides the best short summary of this view in his book “Politics and Administration: A Study in Government”:

The fact is, then, that there is a large part of administration which is unconnected with politics, which should therefore be relieved very largely, if not altogether, from the control of political bodies. It is unconnected with politics because it embraces fields of semi-scientific, quasi-judicial and quasi-business or commercial activity—work which has little if any influence on the expression of the true state will.

For the most advantageous discharge of this branch of the function of administration there should be organized a force of government agents absolutely free from the influence of politics. Such a force should be free from the influence of politics because of the fact that their mission is the exercise of foresight and discretion, the pursuit of truth, the gathering of information, the maintenance of a strictly impartial attitude toward the individuals with whom they have dealings, and the provision of the most efficient possible administrative organization.

The position assigned to such officers should be the same as that which has been by universal consent assigned to judges. Their work is no more political in character than is that of judges.

There is something almost charming as well as comic about this level of naïveté, except that so many people in the administrative apparatus of government still believe it.

Note: This excerpt was taken from Steven F. Hayward’s book “Patriotism Is Not Enough: Harry Jaffa, Walter Berns, and the Arguments That Redefined American Conservatism (Encounter Books, 2017).