One Mom’s Fight for Her Special Needs Son in the Age of Obamacare

Melissa Quinn /

For Marjorie Weer and her family, the Affordable Care Act has been both a blessing and a burden.

The family of four, who live in Mount Pleasant, South Carolina, qualifies for a tax credit, and without the financial assistance, their policy would cost more than $1,200 per month.

But beyond the financial help, Weer’s experiences with Obamacare cut to the core of arguments from the health care law’s defenders for why it was implemented in the first place—and from detractors for why it should be repealed.

Weer’s oldest son, Montgomery, or Monty, was born with spina bifida, a birth defect in which the spinal cord doesn’t develop properly.

The young mother knows well that had Obamacare’s provisions not been in place when her son was born in 2014, it would’ve been extremely difficult—perhaps impossible—for the growing family to find coverage for Monty.

And because the health care law prohibits insurers from limiting how much they will pay in medical bills across the span of an insured person’s lifetime, Weer and her husband, Kevin, no longer have to worry about hitting the maximum insurers would spend on their infant’s coverage.

But even among the good that Obamacare has done for her, Weer also has been hit with the bad.

In the years since Obamacare’s implementation, insurance companies have been fleeing states such as South Carolina and narrowing their networks in an effort to rein in medical claims.

In the Palmetto State, BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina is the only insurer selling coverage on the state’s insurance exchange.

And in the past two years, the company—like many others—narrowed its network.

Now, customers in South Carolina can see only providers located in the state.

For Weer, that means her family can go to the state’s biggest hospital, the Medical University of South Carolina, for care.

But Monty needs to go elsewhere—Boston Children’s Hospital in Massachusetts—for a medical test that will determine his neurological functioning.

And since BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina considers any hospital outside the state to be out of network, Weer has no other choice but to fight for her son.

“In a way, we’re paying for a form of Medicaid,” Weer said, adding:

It’s not Medicaid, but you can’t leave the state for care, and you know, if the doctors that my children need were in the state, that’s great. But not everybody who has a medical license in South Carolina is the right one for for my kid.

A Trend

In an interview with The Daily Signal, Weer was quick to offer BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina the benefit of the doubt.

The company is watching out for its long-term viability, she said, and because much of Obamacare’s enrollment population was sicker and therefore more expensive than anticipated, many insurers have responded by limiting the providers its customers can see.

According to Weer, BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina told her that remaining in the state came with strings attached: they wouldn’t leave South Carolinians without any insurer on the exchange if they restricted their network to in-state care.

In a statement to The Daily Signal, BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina said its decision to narrow its networks was in response to an exchange population that “uses more health care services more frequently.”

“As the only health insurer in the public exchange market in this state, there are limited avenues available to assist in keeping costs as affordable as possible,” Patti Embry-Tautenhan, assistance vice president for corporate relations at BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina, said in an email to The Daily Signal.

“Having a nearly exclusive South Carolina-based provider network, which includes access to the state’s leading academic medical centers, is one way that we can achieve access to a wide range of multidisciplinary services while taking into account our responsibility to our other lines of business,” she said.

And what BlueCross BlueShield did isn’t exclusive to the insurer or South Carolina.

According to a recent study from Avalere, a health care consulting firm, nearly 52 percent of plans sold on the exchanges in 2014 were either a preferred provider organization (PPO) plan or a point of service (POS) plan, which have broad networks.

In 2017, the percentage of PPO or POS products offered on the exchanges dropped to 31 percent.

“That’s a pretty dramatic change, right, over the last few years,” Chris Sloan, a senior manager at Avalere, told The Daily Signal.

Sloan said that since 2014, insurers have been struggling with the cost of the enrollment population, and narrowing networks was the solution.

“One of the ways you can reduce spending or sort of control your costs is to narrow the network and cut better deals with the physicians that are actually in network so you have more preferred rates with them, and they have a higher volume [of patients] because the network is narrower,” he said.

But Sloan added, the narrowing of networks isn’t necessarily a direct consequence of Obamacare.

Health insurers were trending toward narrower networks, he said, and some were beginning to offer “tiered networks” to give consumers the option to choose between cost and access.

A cheaper plan, generally on an insurer’s first tier, would have a limited number of providers. A more expensive plan, generally the second or third tier, would have a wider network of doctors, specialists, and hospitals to choose from.

Additionally, Sloan said, narrow networks aren’t necessarily bad—for some consumers.

“Just because there are fewer doctors in networks doesn’t mean you’re getting worse care,” he said. “It can also mean you’re getting better care if you’re just focused on getting really good, quality physicians and [insurers are] steering you, by having narrow networks, toward those good physicians.”

Still, not every consumer may want to have a limited number of physicians to choose from.

“It’s too early to tell if narrow networks are good or bad for consumers,” Sloan said. “It’s a mix of both.”

Cleaning Up Their Mess

For Weer and her family, it’s clear that restricting coverage to doctors in-state is a bad thing.

And it’s not an issue the Weers have had to deal with in the past.

When Monty was just 4 months old, in 2014, Weer began to take him every other weekend to see a doctor at Shriners Hospital for Children in St. Louis, Missouri, to treat his bilateral clubfeet, a condition associated with spina bifida. This went on for three months.

Monty had his own insurance plan through Aetna and also was enrolled in South Carolina’s Medicaid program via what is known as a Katie Beckett waiver.

That original insurance plan fully covered Monty’s care in St. Louis and, Weer said, she can’t remember ever having to pay for her son’s medical services after he hit his deductible.

Then, for 2016, Weer and her husband enrolled themselves, Monty, and their newborn daughter in a new plan through BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina.

That plan allowed Monty to see doctors at Boston Children’s Hospital in Massachusetts, the top-ranked hospital in neurology and neurosurgery for pediatrics, according to U.S. News and World Report.

“They have a better test for Montgomery’s neurological needs, and so we thought, well, we’ll just transfer his care up there,” Weer said of the decision to go to Boston Children’s Hospital.

What the new plan didn’t cover, though, was the Medical University of South Carolina—the very hospital Weer is restricted to now.

In 2017, though, that all changed.

BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina altered the design of its plans, so only hospitals located in South Carolina were considered in-network.

For Weer, it isn’t that the Medical University of South Carolina is a bad hospital, and she said Monty and her daughter will go there for care.

But for the “biggies,” Weer said it’s not the best for her son.

For one, Boston Children’s Hospital offers a more in-depth neurological test—costing $4,000 without insurance—that will determine a baseline of Monty’s nerve functioning.

Additionally, the doctors in Boston have been responsive to Weer’s inquiries, answering her emails and text messages no matter the time of day.

So after learning BlueCross BlueShield no longer would cover Monty’s medical services in Boston, Weer began working—ideally—to convince the insurer to cover Monty’s care at Boston Children’s Hospital.

“The most I resent in all of this,” Weer said, “is the time away from my kids because the people in Washington, D.C., who have no business and no knowledge about health care just decided to screw this all up and left moms like myself to clean up their mess.”

‘Well-Intentioned’

Weer’s experiences with a change in network weren’t necessarily a direct consequence of Obamacare, Avalere’s Sloan said.

But he acknowledged that issues with the health care law—specifically a lack of choice in insurers—certainly compounded the problem for consumers such as Weer.

Prior to the Affordable Care Act, Weer said, she and her husband had many insurers to choose from.

But now, since South Carolinians have only BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina, they don’t have the option to shop around for a plan that fits their needs.

“I want to be able to take care of my kids,” Weer said, “but I need options for my special needs son.”

Policymakers cite lack of competition and choice as one of the most dire consequences of the health care law.

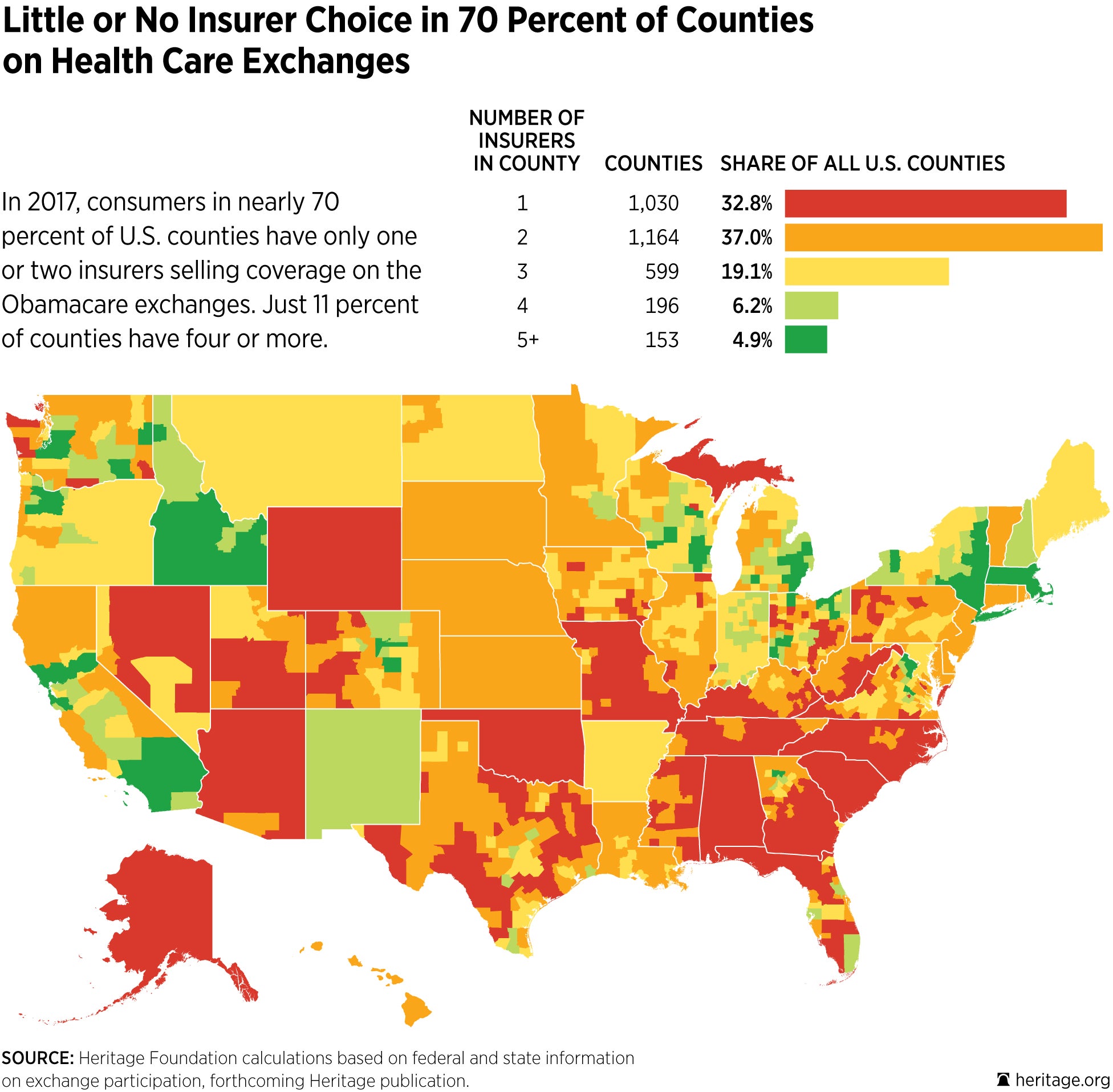

House Speaker Paul Ryan frequently rattles off statistics demonstrating the lack of choice consumers have on the exchanges: 1 in 3 counties nationwide have only one insurer, and 70 percent of counties have only one or two insurers.

Additionally, consumers in five states—Alabama, Alaska, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Wyoming—have only one insurer on the exchange.

Ryan and his fellow Republicans argue that by repealing Obamacare and replacing it, Weer and other consumers will have more options and lower costs.

“The Affordable Care Act, though incredibly well-intentioned, has proven disastrous from the standpoint of rising premiums and increasingly limited choices,” Rep. Mark Sanford, R-S.C., told The Daily Signal.

In Sanford’s home state, the number of insurers selling plans on the exchange decreased from three to one in the years since Obamacare took effect. Premiums increased an average of 29 percent from 2016 to 2017.

“It’s crowding a lot of folks out,” Sanford, who is Weer’s congressman, said. “That has a real consequence for people at home who have more limited choices that may or may not fit with their health care needs.”

Last week, Sanford and Sen. Rand Paul, R-Ky., outlined their replacement for Obamacare.

Their proposal, which has the endorsement of the roughly 40-member House Freedom Caucus, relies heavily on the expansion of health savings accounts, also known as medical savings accounts, and creates a $5,000 tax credit for individuals and families who contribute to those accounts.

The Sanford-Paul bill also allows consumers who don’t receive coverage through an employer to deduct the cost of premiums from their taxable incomes, and allows individuals and families to band together through membership in an association health plan to buy insurance.

Sanford said their proposal focuses on two things: “empowering the consumer and creating a more robust marketplace.”

The South Carolina congressman said the Affordable Care Act actually “makes less expensive insurance unlawful” and deters young people from signing up for coverage.

Sanford said the health care law also allows consumers who receive a medical diagnosis to sign up for coverage the next day, which ends up costing the insurance companies money.

“It’s been really harmful to insurance companies, and their way of getting around that at times is to constrict the choice that consumers have with negative impact in terms of quality of care,” he said.

Sanford said he hopes that by enacting some of the reforms included in his proposal, more consumers, especially younger consumers, will sign up for insurance, premiums will go down, and more insurers will expand their offerings in places like South Carolina.

“I don’t think there’s a single silver bullet that will better health care,” Sanford said. “But in the aggregate if you do enough of these things, you end up with a consumer that is much more empowered relative to where they are now.”

A Blessing

Like many other Americans across the country who are turning up at town halls and public events for their members of Congress, Weer has been watching GOP lawmakers closely.

She wants to know how the health insurance landscape will change once Obamacare is repealed, and she’s sick of waiting for answers.

“This mama has had enough … I know this is a monster to undo, but you’ve had years to come up with something,” Weer said of a Republican plan to replacement Obamacare. “What I’ve been through, trying to navigate these waters, having a kid with spina bifida isn’t the issue. Dealing with the insurance is the hard part, and trying to keep your Christian testimony in check.”

After spending weeks bouncing among phone calls with South Carolina’s Medicaid system, Boston Children’s Hospital, and BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina, Weer finally was able to get some concessions from the insurance company.

At first, BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina said it would charge Weer its in-network cost for Monty’s neurological test at Boston Children’s Hospital, but none of those expenses would go toward the family’s $6,300 deductible.

Additionally, the Weers would be responsible for the balance bill—the difference between an in-network provider’s negotiated rate and the full price for a service.

Weer and her husband began to crunch the numbers, and she once again got on the phone with Boston Children’s Hospital to determine how much the test would cost with insurance, as well as how much they may have to fork over for the balance bill.

“If we’re still stuck with a $4,000 or $5,000 bill, we’re a middle-class family,” she said. “That’s a big deal.”

But then, late last week, Weer’s case manager with BlueCross BlueShield of South Carolina called and said the insurance company would cover the full cost of Monty’s care at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Weer knows that things could still change, but she’s grateful her months of back-and-forth ended happily.

“Today,” she said, “I’m going to take this as a blessing.”