Amid War, Ukraine’s Population Continues to Dwindle

Nolan Peterson /

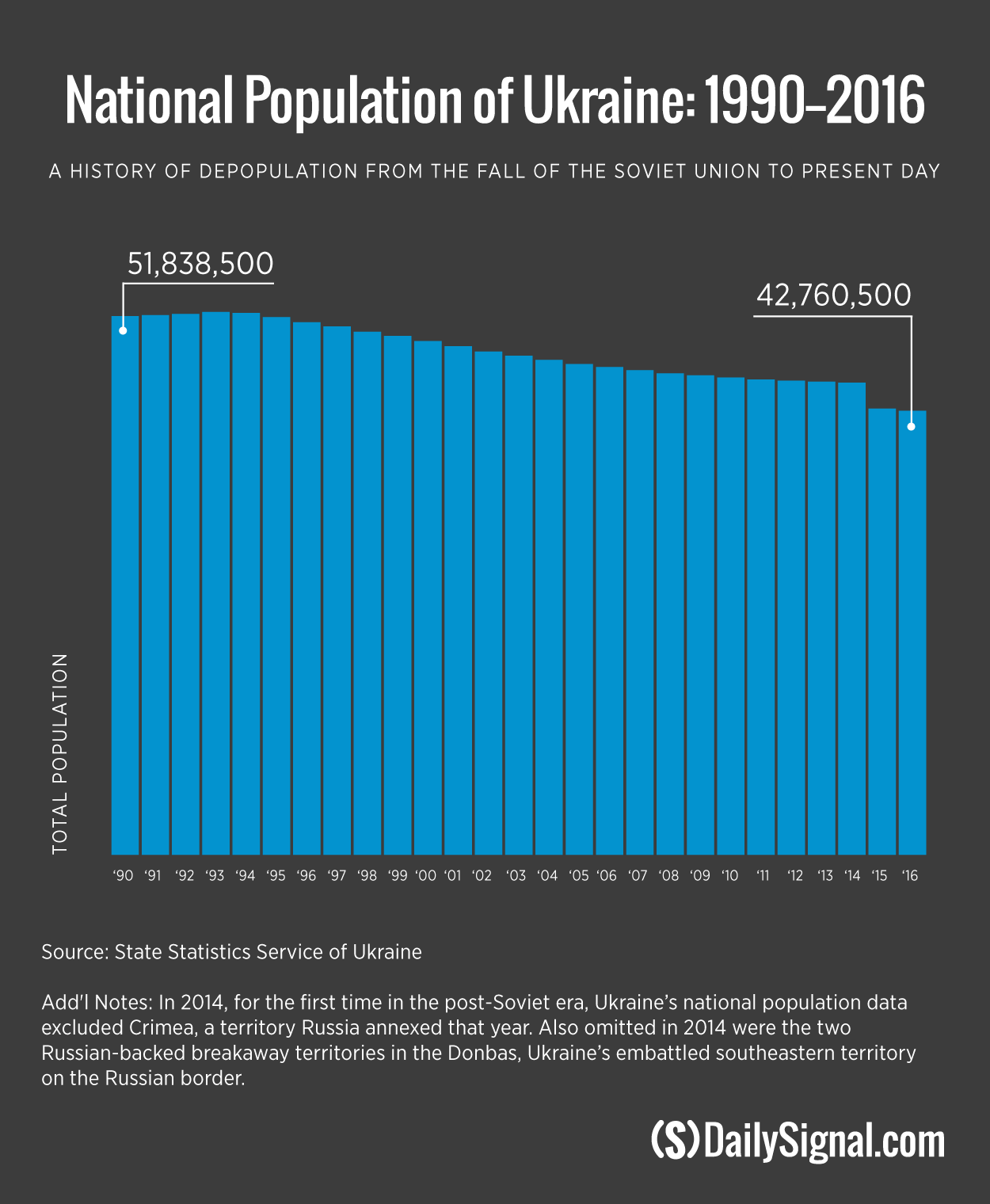

KYIV, Ukraine—Ukraine’s population decreased by about 170,000 people in 2016, the government reported last month, underscoring a demographic trend that began after the country declared its independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, and which threatens to derail the country’s political and economic development.

“This is a serious problem for the country,” Alex Ryabchyn, a member of Ukraine’s parliament, told The Daily Signal. “People are dying due to bad living conditions, declining environmental standards, or the war. Another problem is that the most active workforce is considering emigration.”

More people are dying than are being born in Ukraine. In 2016, every birth in Ukraine was matched by 1.5 deaths, according to a January report by the State Statistics Service of Ukraine.

By the end of 2016, Ukraine’s population had decreased by about 9.5 million from its 1993 peak of 52,244,100—a net 18 percent drop. The numbers, however, require a bit of context.

In 2014, for the first time in the post-Soviet era, Ukraine’s national population data excluded Crimea, a territory Russia annexed that year. Also omitted in 2014 were the two Russian-backed breakaway territories in the Donbas, Ukraine’s embattled southeastern territory on the Russian border.

Consequently, Ukraine’s population dropped by nearly 2.5 million in 2014 alone due to these lost territories. Yet, that year’s territory losses simply exacerbated a long-term demographic trend.

In 2013—the last year the populations in Crimea and the Donbas were counted—Ukraine’s population had already decreased by about 6.7 million people from 1993, roughly equivalent to the number of Ukrainians who were killed during World War II.

Causes

The State Statistics Service of Ukraine reported the leading cause of death in 2016 was heart disease (68 percent of deaths), followed by cancer (18 percent of deaths).

According to faculty at the Kyiv National Economic University, the country’s persistently high mortality rate is due to low-quality health care, an increase in the number of epidemic diseases, and the widespread abuse of alcohol and drugs.

Iryna Fedets, senior research fellow at the Institute for Economic Research and Policy Consulting, a Ukrainian think tank, attributed Ukraine’s post-Soviet depopulation to poor quality of life and limited access to quality health care.

“Also, alcohol, and food—cheaper food tends to be worse for health,” Fedets said. “And the environment—pollution, and Chernobyl.”

On April 26, 1986, reactor No. 4 at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant—about 84 miles north of Kyiv—sent a plume of radioactive material into the atmosphere. The resulting fire released as much radiation as 400 Hiroshima bombs, fatally contaminating the surrounding area and sending radioactive fallout across Europe.

The disaster killed 31 in its immediate aftermath and has caused thousands of early deaths in Ukraine and throughout Eastern Europe.

Back in the USSR

The consequences of depopulation primarily affect young working Ukrainians.

“In terms of the economy, this will put more and more pressure on the younger, working people to provide pensions for the retired people,” Fedets said. “Those who work will have to pay more.”

A 22 percent “salary fee” is currently deducted from Ukrainians’ incomes to pay for pensions.

Beyond the economic consequences, depopulation is also a threat to Ukraine’s post-revolution political reformation.

Some analysts attribute the lack of men in Ukraine to population losses in World War II. (Photos: Nolan Peterson/The Daily Signal)

More promising economic opportunities abroad are luring talented, educated young Ukrainians away at a moment when many say the country’s future hinges on ushering in a new generation of young political and business leaders who are uncorrupted by self-injurious Soviet cultural habits, such as a tolerance for corruption.

With 86.3 men for every 100 women, Ukraine has the sixth-lowest ratio of men to women among all countries in the world.

Also, the life expectancy difference of 10 years between Ukrainian men and women (66 and 76 years, respectively) is the fifth-biggest among all countries in the world, highlighting how lifestyle choices among Ukrainian men, particularly their proneness to alcoholism, contributes to a high mortality rate.

As a point of comparison, the average worldwide gender life expectancy gap is 4.5 years, and the average worldwide male to female ratio is 101.8 men for every 100 women, according to the Pew Research Center.

Ukraine’s life expectancy gender gap and its overall population decline reflect a demographic crisis that emerged throughout the former Soviet Union after its breakup.

Among the 10 countries in the world with the fewest men per women, seven are former Soviet countries, according to a 2015 Pew Research Center study. And the six countries in the world with the biggest gender gaps in life expectancy are, in order: Belarus, Russia, Lithuania, Ukraine, Latvia, and Kazakhstan—all former Soviet countries.

With 86.3 men for every 100 women, Ukraine has the sixth-lowest ratio of men to women among all countries in the world.

According to medical and economic studies of this trend, the life expectancy gender gap in the former Soviet Union is most commonly attributed to rampant alcoholism and a penchant for risky behavior among men.

Also, some say the gender imbalance in post-Soviet countries is a lingering demographic consequence of the millions of men who died fighting in World War II.

Estimates vary, but World War II killed about 14 to 16 percent of the Soviet Union’s overall population. About 7 million Ukrainians died in the war (including 600,000 Ukrainian Jews killed during the Holocaust) from 1939 to 1945, which corresponds to roughly one out of every five Ukrainians alive in 1940.

“This region has been predominantly female since at least World War II, when many Soviet men died in battle or left the country to fight,” the 2015 Pew Research Center report said.

Hard Choices

Depopulation is a stark barometer of Ukraine’s national mood.

Many Ukrainians have made a conscious choice to have fewer children, or to delay parenthood, due to political and economic instability, as well as the ongoing military conflict in the Donbas.

“You can get used to the shooting and the explosions, but I feel like my life has stopped,” 23-year-old Olga Murza, manager of a coffee shop in the front-line town of Mariupol, told The Daily Signal in an earlier interview.

The war’s front lines are only about 10 miles from Mariupol—a city of about half a million people—and the artillery is sometimes loud enough to shake windows in the city center.

A Ukrainian soldier in the Azov Battalion at the conclusion of his military training before deploying the war zone.

“I want peace because I have ideas and hopes for my future,” Murza said. “I want to live my life and start a family,” she added, “and I can’t do anything because I don’t know what will happen in a month, or a year.”

According to a 2012 UNICEF study, 50.7 percent of all married Ukrainian women did not want a child in the next two years. The average ideal family size in Ukraine, according to the report, was 1.9 children.

As a point of comparison, according to a 2013 Gallup poll, Americans said the ideal number of children per family was 2.6.

And for those Ukrainians wishing to start families, many would choose to do so in another country if they could.

Rampant corruption, years of war, and economic and political instability have collectively fostered a pessimistic attitude among many young Ukrainians about their country’s future. Consequently, many young Ukrainians, millennials in particular, have moved abroad in search of work, or would choose to do so if they had the opportunity.

“I’d say 80 percent of my friends are already abroad or plan to move abroad,” 21-year-old Valentyn Onyshchenko told The Daily Signal.

This correspondent asked a group of high school students in Kyiv if they would rather stay in Ukraine or move abroad. Only one student out of 17 preferred to live in Ukraine—he wanted to be a priest.

Ryabchyn, the Ukrainian member of parliament, said the government needs to do more to entice Ukrainians living abroad who want to return and help rebuild the country.

“After the Revolution of Dignity in 2014, people tended to return to Ukraine looking for possibilities,” Ryabchyn said, referring to the 2014 revolution, which overthrew former Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych.

“It’s a shame,” he added. “The government should start supporting small and medium-sized enterprises and create job opportunities to increase Ukrainians’ well-being.”

According to a 2015 survey jointly funded by the United Nations and the Ukrainian government, 55 percent of Ukrainians aged 14 to 35 said they would choose to move abroad temporarily, or for good.

From 2009 to 2014, the number of Ukrainian students studying abroad increased by 79 percent.

And since 2014—the year of Ukraine’s revolution, the Russian annexation of Crimea, and the beginning of the war in the Donbas—the number of Ukrainian students abroad jumped 22 percent, comprising 47,724 Ukrainian students studying in 34 countries, according to CEDOS, a Ukrainian think tank.

Of those surveyed, 34 percent cited the ongoing conflict in the Donbas as a reason for leaving the country. A lack of economic opportunities was another top reason for emigrating, followed by the explanation, “There is no real democracy and legality in Ukraine.”

Despite the migratory aspirations of many young Ukrainians, Ukraine still nets more immigrants than emigrants.

Last year, 7,618 more people immigrated into Ukraine than left the country, according to government statistics. And in 2015, Ukraine had 14,233 more immigrants than emigrants.

However, the migration data could be misleading, Fedets said, since many Ukrainians who move abroad retain their Ukrainian passports and are still counted as part of the population.

“Eventually, to stop the population loss, Ukraine will need to improve economic conditions and to become more calm and secure place to live—that means that the active fighting has to stop and a stable peace process has to take place,” Fedets said. “Basically, the war will have to move down in headlines.”

Family Planning

Ukraine’s independence from the Soviet Union in 1991 proved to be an unremitted economic catastrophe, which ultimately made parenthood unaffordable for many Ukrainians.

By 1996, Ukraine’s gross domestic product had fallen by about 60 percent from its 1990 level. In comparison, the U.S. GDP fell 30 percent during the Great Depression from 1929 to 1933.

Ukrainian industrial production reduced by more than half from 1991 to 1996—a bigger drop than what the Soviet Union experienced during World War II when half the country was occupied by Nazi Germany, and 24 million people, both civilians and military, were killed.

With the Soviet Union’s breakup, many Ukrainians saw their life savings basically disappear overnight. Hyperinflation from 1992 to 1994 left about 80 percent of Ukrainians in poverty and roughly one-quarter of the population unemployed.

Consequently, the purchasing power of the average Ukrainian salary for basic food items fell dramatically from 1992 to 1994. For Ukrainians on minimum wage, their purchasing power for basic food items fell by as much as 95 percent, according to studies from the Kyiv National Economic University.

The economic meltdown dissuaded many Ukrainian families from having children. Consequently, Ukraine’s female fertility rate fell precipitously continuously throughout the 1990s, reaching a low point of 1.1 children per woman in 2000.

By 2016, the fertility rate had slightly recovered back up to 1.5. This is, however, still below the replacement fertility rate of at least 2.1 needed for zero population growth in developed countries.

And despite the uptick in fertility rate since 2000, total Ukrainian births have continued to decline. There were more than 365,000 births in Ukraine in 2016, down from about 412,000 in 2015, and 466,000 in 2014.

“Since 1991, there have been always more deaths than births in Ukraine,” Fedets said.

The Family

Ukraine’s abortion and marriage rates have both declined since the Soviet Union’s breakup, underscoring Ukrainians’ reluctance to start families and have children.

Ukraine’s marriage rate decreased from 9.3 marriages per 1,000 people in 1990 to 7.8 marriages per 1,000 people in 2015, according to government data.

The reduction in Ukraine’s abortion rate has been more dramatic.

In 1990, according to the World Health Organization, Ukraine registered about 1,550 abortions for every 1,000 births—about 7.8 times higher than the average rate that year among countries that would ultimately comprise the European Union in 1993.

However, by 2013, the last year abortion data for Ukraine was available, the number of Ukrainian abortions per 1,000 births had fallen to 166—which was lower than the EU average of about 220 that year.

According to Ukrainian analysts, the precipitous drop in Ukraine’s abortion rate after 1991 is likely attributable to better family planning education, and the more widespread use of contraceptives.

Many Ukrainians have made a conscious choice to have fewer children, or to delay parenthood, due to political and economic instability, as well as the ongoing military conflict in the Donbas.

Contraceptives were not widely available in the Soviet Union. But abortions, which were legalized in the Soviet Union in 1955, were free for working women and cost nonworking women about four or five Soviet rubles (about $2.50 to $3.15, according to the exchange rate before Nov. 1, 1990).

“Shortages of birth control devices lasted throughout the Soviet era,” Deborah A. Field wrote in her 2007 book “Private Life and Communist Morality in Khrushchev’s Russia.”

“Despite the pleas of doctors and health officials, contraceptive production was never made a national priority, leaving abortion and abstinence as the two forms of birth control available to most women,” Field wrote.

Also, cultural stigmas (perpetuated by the Communist Party) against talking openly about sex hampered family planning education in the Soviet Union.

After 1991, however, family planning education improved in Ukraine. Concurrently, contraceptives became more widely available and abortions became much more expensive.

Today, legal abortions in Ukraine cost about $180. But the costs are not limited to the procedure itself. Ukrainian women also have to pay for a three-day hospital stay and a post-abortion treatment protocol, which collectively double the overall cost of the procedure to almost $400.

In a country with an average monthly salary of about $164, abortions are, consequently, cost prohibitive for many Ukrainian women.

In contrast, a month of birth control pills from a pharmacy in Kyiv costs between 150 to 500 hryvnias (about $5.40 to $17.80), depending on the brand and type. A prescription is not needed.

According to UNICEF, 52 percent of Ukrainian women currently use a method of contraception.

Depopulation is a major challenge for Ukraine’s economic and political development. For its part, the Ukrainian government has introduced measures to reverse the trend, such as a financial assistance program for new parents.

In 2017, the government offered a 41,000 hryvnia payout per child (about $1,500), split into regular payments over 36 months.

While government assistance relieves some of the financial burden of parenthood, reversing Ukraine’s population decline will ultimately depend on the country’s economic and political stability, and an end to the war.

“Ukrainians want to live a peaceful and thriving life in their country and I think it is a reasonable goal,” Fedets said.