Obama’s Commutation of Manning Sentence Sends a Horrible Message to Service Personnel

Cully Stimson /

Exercising his authority under Article II, Section 2 of the U.S. Constitution, President Barack Obama commuted the court-martial sentence of convicted felon Chelsea Manning, formerly known as Bradley Manning.

Although there is no dispute that Obama had the legal authority to commute the former Army private first class’ sentence, the president and his advisers had to know that any relief granted to Manning would be terribly controversial, and for good reason.

Commuting Manning’s sentence sends a horrible message to everyone who serves in the U.S. military, emboldens those who seek to harm the United States, and disheartens countless Americans—in and out of uniform.

It is important to remember the facts of the case. This was not a whodunit. This was not a case where motive excused Manning’s behavior, as some Manning supporters argue.

This is a case about an Army private first class who, while stationed abroad, having access to top secret and other classified material, decided to steal that material and give it to WikiLeaks, knowing full well that WikiLeaks would publish the material for the world to see.

There is no dispute as to the facts of the case, as in some instances of presidential pardons. After being caught, Manning was sent to a general (felony) court-martial. After consulting with defense attorneys, Manning decided to plead guilty.

In military guilty pleas, the accused must describe for the military trial judge facts sufficient to convince the judge, beyond a reasonable doubt, as to each and every element in each crime. The accused discusses these facts with the judge while under oath, and those discussions last a long time.

This case was no different.

According to the facts developed in the case, and discussed at the court-martial, between November 2009 and May 2010, Manning was deployed overseas, and during that deployment, had access to secret and top secret data. Manning had a duty not to disclose the data to any unauthorized person.

Nevertheless, Manning downloaded 400,000 classified files from the Iraq war, some 91,000 files from the Afghan war, around 250,000 U.S. diplomatic cables (emails), sensitive and classified U.S. airstrike videos, and classified documents and files from Guantanamo Bay, including classified assessments of Guantanamo terrorist detainees.

Manning placed that material on a SD-type card, and took it. Manning then gave that highly classified and sensitive material to WikiLeaks, knowing full well that it would (1) publish the material and (2) that the material could and likely would fall into the hands of our enemies.

The Army charged Manning with, among other things, aiding the enemy—a crime that under certain circumstances could result in the death penalty.

Eventually, Manning decided to plead guilty instead of contesting the charges against him. The maximum possible sentence to those charges to which Manning pleaded guilty was 136 years. In other words, it would have been lawful for the trial judge to sentence Manning to 136 years.

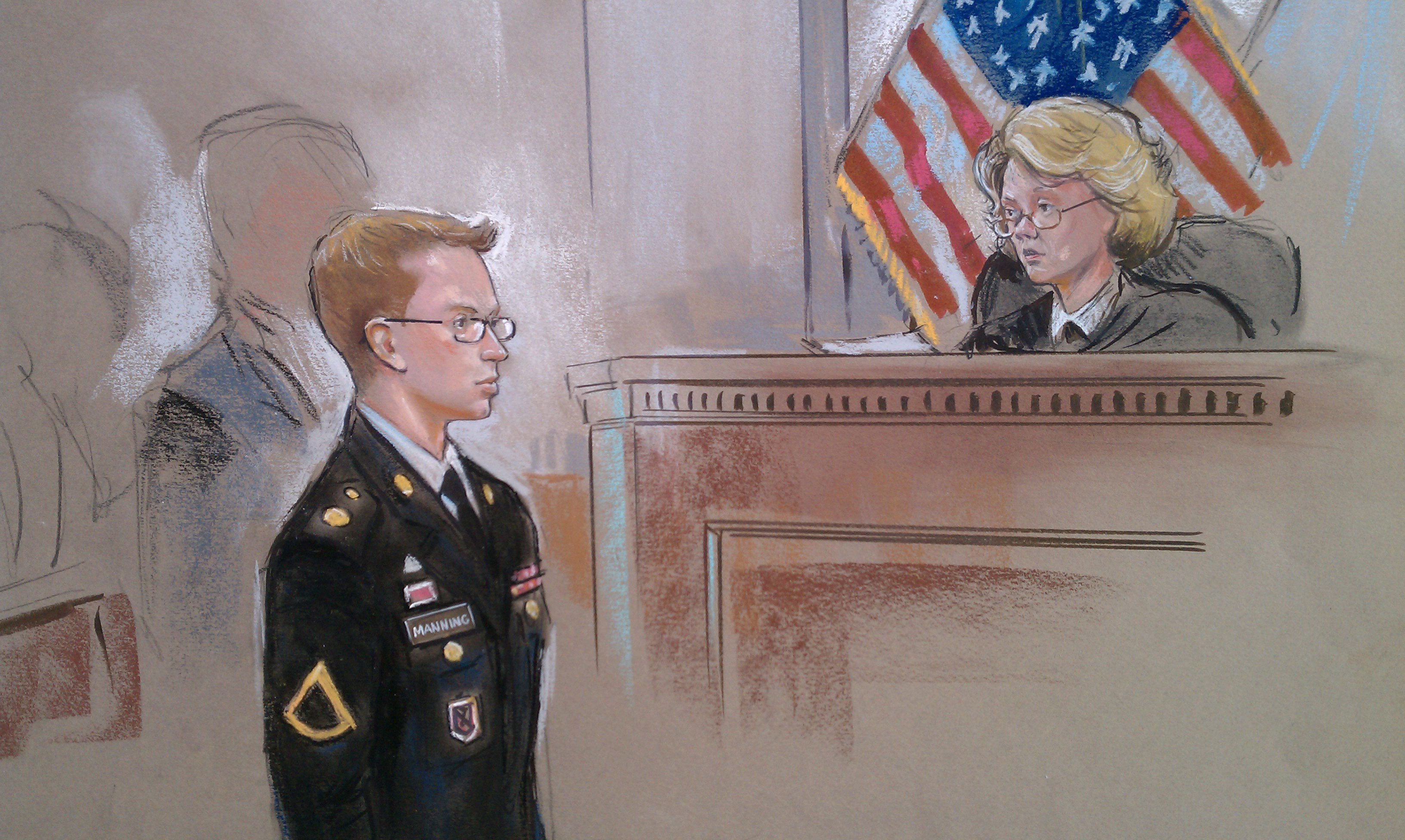

A courtroom sketch shows Army Pfc. Bradley Manning facing a military judge, Col. Denise Lind, during a court-martial hearing March 15, 2012. (Photo of sketch by William Hennessy Jr.: CourtroomArt/EPA/Newscom)

At the sentencing hearing, the government presented evidence in aggravation of these crimes. Army Brig. Gen. Robert A. Carr, a top Pentagon intelligence official, testified that Manning’s disclosures “affected our ability to do our mission,” and endangered U.S. ground troops in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Patrick Kennedy, the undersecretary of state for management, testified that Manning’s actions sent the State Department into crisis and prompted a costly effort to assess the damage that the leaks had done.

Kennedy asserted, “I believe my colleagues abroad are still feeling [the results of the leak].”

Maj. Gen. Michael Nagata, the deputy commander of the U.S. defense attaché in Pakistan, testified that Manning’s actions had a strong negative effect on the mission of the Office of Defense Representative in Pakistan.

Col. Denise Lind, the military trial judge, sentenced Manning to 35 years and a dishonorable discharge from the U.S. Army. Manning filed an appeal in May 2016, which is now moot given the president’s commutation.

To some, Manning was a whistleblower who deserved a pardon, or at least a sentence commutation. Indeed, one of the videos Manning gave to WikiLeaks showed U.S. military personnel in Iraq engaged in a deeply troubling, if not illegal, shooting incident.

But there was so much more to Manning’s crimes than exposing that killing.

By downloading hundreds of thousands of secret documents about some of the most sensitive information related to the war effort in Iraq and Afghanistan, by disgorging highly sensitive diplomatic emails for the world to see, and recklessly exposing top secret files of terrorist detainees we held at Guantanamo, Manning betrayed the oath to our country, armed our enemies with information that they could only dream about acquiring, and forced our government to expend untold hours and money to minimize the damage inflicted by this criminal conduct.

Those who applaud the commutation also argue that the sentence Manning had received was “excessive and disproportionate.”

Yet it is difficult to imagine, much less point to, another case of a U.S. military member who single-handedly stole the volume of classified information to an unauthorized source (WiliLeaks), or one that caused the multi-layered damage to U.S. military security and diplomatic harmony that Manning caused.

Manning’s defenders argue that the mental health of a “vulnerable person” should act as a mitigating circumstance with respect to the sentence. But that argument was presented, in full, to Lind before she sentenced Manning.

Under the law, military trial judges are required to take into account all aggravating and mitigating evidence before sentencing the accused. Thus, Manning already received the benefit of gender identity issues when sentenced in the first place.

The “mercy” that some argue for was actually granted by the trial judge: She didn’t sentence Manning to the 50 or 100 or 136 years Manning could have served.

And everyone in the military justice system knows that a 35-year sentence of confinement, assuming good behavior while in custody, in reality will result in a much shorter sentence.

Manning was eligible for parole after serving 10 years, and was earning at least five days a month of good time credit and eight days a month of abatement credit. Given those 13-day per month credits (or more), Manning’s mandatory supervised release date could have been as early as the 18-year mark, and he could have been paroled after a mere 10 years.

In other words, Manning could have walked out of prison, even without Obama’s actions, in three years’ time.

Finally, it bears mentioning that U.S. military members across the globe carry out their duties, for the most part, with honor and fidelity. Many have access to secret and top secret material. Some have access to Special Access Program information—the most highly classified material our government possesses.

They guard this information with their lives, and for good reason. They know that if they violated their oaths by stealing this information and providing it to our enemies, American lives and national security would be in grave danger.

By commuting Manning’s richly deserved sentence, Obama is sending a horrible message to dedicated U.S. public servants, in and out of uniform, that honoring their responsibility to keep national security secrets from the public eye isn’t all that important.

This is a slap in their face.

Note: This article was updated after publication to provide added details about Manning’s prison sentence.