From Pajama Boy to Green Ninja, the Government’s PR Spending Operates in Dark

Lauren Bowman / Romina Boccia /

U.S. government spending on public relations campaigns, including NASA’s Green Ninja videos on global warming and the Pajama Boy ads for Obamacare, should raise serious questions about fiscal responsibility and where to draw the line between appropriate communication and propaganda.

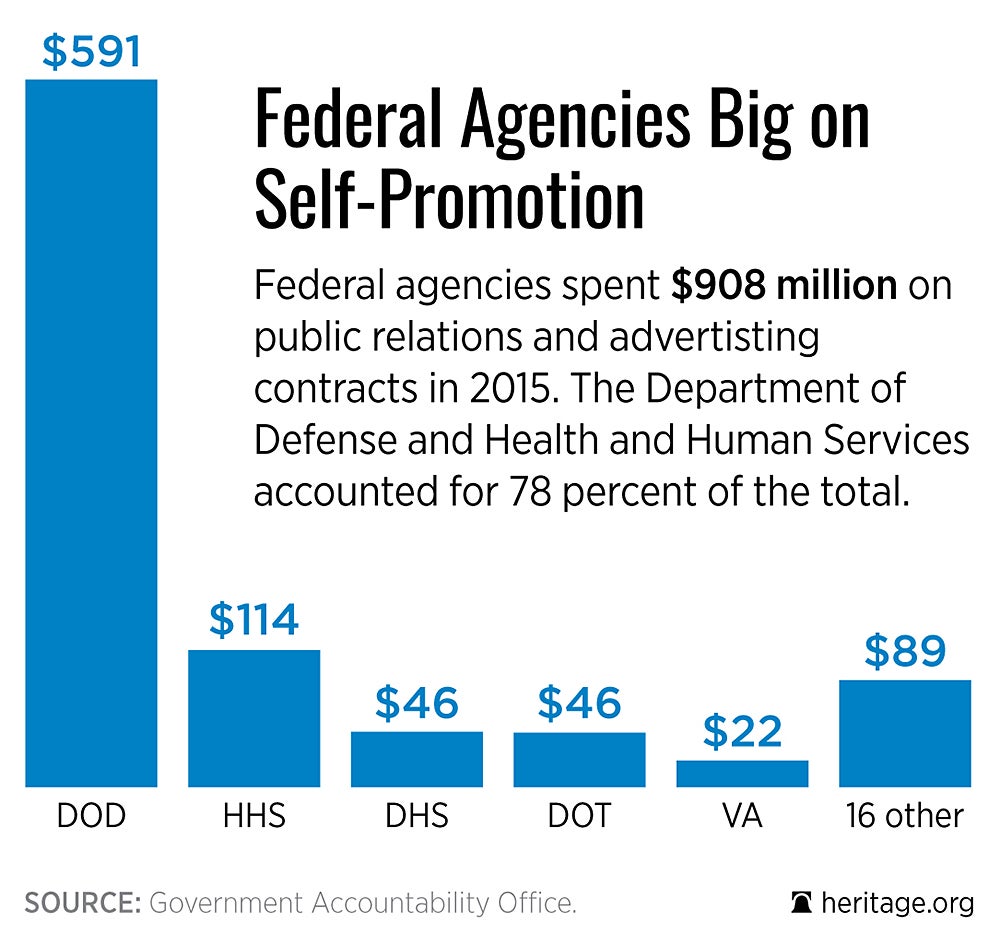

The government spent about $1 billion annually on advertising and public relations from 2006 to 2015, according to a Government Accountability Office report on such federal spending.

The largest government agencies spent the most, with the departments of Defense and Health and Human Services making up the majority of PR expenditures.

Senate Budget Chairman Mike Enzi, R-Wyo., requested the study in an attempt to identify how much the government is spending on PR. As it turns out, it’s quite difficult to separate the government’s spending on public relations from other spending.

The $1 billion figure cited by the GAO excludes numerous possible PR activities such as “signs, advertising displays, and identification plates” because, the agency said, it could not effectively separate them into items used for PR-related purposes as opposed to other purposes.

So much PR spending appears to be largely unaccountable “black box” spending.

Some of this money likely goes toward legitimate public communications purposes, but much of the spending probably is wasteful and some raises concerns that government may run afoul of propaganda rules.

Two primary legal restrictions on government employees are relevant in the context of agency PR spending: the Anti-Lobbying Act and appropriations language that limit spending for “publicity or propaganda purposes.” However, officials generally don’t enforce these provisions.

In addition to this vagueness in defining publicity, propaganda, and lobbying, no congressional committee oversees government communications to make sure agencies follow these guidelines. The GAO does not routinely research and report on agency communications, unless specifically requested to do so.

One recent example of an agency getting in trouble for violating the rules is the Environmental Protection Agency, which acted more like an advocacy group than a federal agency when soliciting public comments for its controversial water rule.

The EPA violated restrictions in appropriations law against publicity or propaganda when pushing its water rule using social media, the Government Accountability Office found.

Lack of oversight and vague restrictions mean that many agencies waste taxpayer money on frivolous and inappropriate communication.

For instance, the State Department spent $630,000 to convince people to “like” the department’s Facebook page.

NASA spent $390,000 on a campaign to promote Green Ninja, a superhero the agency used to educate children about global warming and tell Americans what not to eat. You shouldn’t eat steak, according to the Green Ninja, because it is bad for the environment.

The State Department spent $62,098 on cooking videos and online cooking demonstrations.

Who can forget the infamous “Pajama Boy” ad designed to get young people to enroll in Obamacare in 2013? The ad showcased a man in his 20s wearing flannel onesie pajamas. The ad read: “Wear pajamas. Drink hot chocolate. Talk about getting health insurance. #GetTalking.”

How do you plan to spend the cold days of December? http://t.co/Rwf5AYc3bG #GetTalking pic.twitter.com/PBQ397yLf4

— Barack Obama (@BarackObama) December 17, 2013

Based on number of employees, the federal government is the second-largest PR firm in the world, according to an oversight study by Open the Books. In 2014, the government spent almost $500 million on salaries for public relations employees.

This spending not only is wasteful at a time our national debt is reaching record-breaking levels, but much of it is used inappropriately for propaganda.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau spent the largest share of its budget on PR, when compared to other agencies. The agency has a $12.5 million contract with GMMB Inc. for an ad campaign to grow trust and awareness.

The move caused concern because GMMB Inc. is the advertising firm used by both the Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton presidential campaigns. Some question whether political favoritism was at play.

Another example is the Labor Department’s trying to persuade people to adopt Obama’s policy of raising the minimum wage. Labor officials tweeted out a video of a hot dog with mustard spelling out #RaiseTheWage.

It's #NationalHotDogDay! DYK the avg hot dog vendor likely makes < $9/hr? Let's reward work & #RaiseTheWage: https://t.co/96AnBW7qDV

— U.S. Department of Labor (@USDOL) July 23, 2015

The tweet read: “It’s #NationalHotDogDay! DYK the avg hot dog vendor likely makes <$9/hr? Let’s reward work & #RaiseTheWage.”

It clearly crossed the line between education and advocacy. Congress can get a better handle on what currently is unaccountable “black box” spending on government PR. Greater transparency and oversight will help make agencies more accountable for such spending. Cuts in allotted PR funding also can help to curb waste in this area.

Congress is considering a different approach in legislation called the Taxpayer Transparency Act of 2015. It would require federal agencies to label their ads and media as having been government-produced. This reform does not go far enough.

Kevin R. Kosar and John Maxwell Hamilton, experts on government PR spending, recommend that agencies should have to cite the sources of their “facts.”

To enhance accountability, Kosar and Hamilton recommend that Congress require agencies to report annually on the number of public communications they produce, the number of staff members who assist in communications, and their costs. The GAO then could use this data to publish an inventory of government PR spending.

Enhancing accountability and transparency for government communications with the public and Congress is a critical step to rein in inappropriate, wasteful government PR spending.

It’s on Congress to ensure agencies properly allocate such funds and, when they veer into propaganda territory, are held accountable for misuse of funds.