How Lawmakers Can Block Obamacare Bailouts

Edmund Haislmaier /

Members of Congress working to block any Obamacare bailouts got two pieces of good news recently.

One was that the Department of Justice filed robust and persuasive motions to dismiss the lawsuits brought by insurers seeking payment for the rest of their Obamacare “risk corridor” program claims.

The risk corridor program collects money from insurers with lower-than-expected costs and transfers it to insurers with higher-than-expected costs. However, because most insurers had higher costs (while only a few had lower costs) in 2014, the available funding reimbursed only 12 percent of risk corridor claims filed by insurers losing money on Obamacare.

The other was that the Government Accountability Office issued a legal finding that the Department of Health and Human Services acted illegally when it diverted into the “reinsurance” program (for insurers offering Obamacare coverage) revenues that Congress had ordered paid to the Treasury.

The reinsurance program reimburses insurers for large claims (those between $45,000 and $250,000) incurred by “high-risk individuals in the individual market.”

Yet while both developments are good news, it’s still too early to declare victory. Congress needs to keep pressing forward on both fronts—while also preparing to head off a possible third bailout attempt.

With respect to the risk corridor lawsuits, congressional leaders are reportedly working on legislation that would prevent payments to the insurers in the event that the Obama administration agrees to settle their claims.

However, any such legislation would have to be signed by the president. That makes its prospects problematic, unless it is added to other legislation that the president is likely to sign.

Another option gaining attention in Congress would be for the House of Representatives to challenge in federal court the constitutionality of any such settlements—as they would constitute a blatant attempt to circumvent Congress’ constitutional authority to determine how federal funds are spent through appropriations.

Indeed, Seth Chandler, a University of Houston law professor, called for such action back in March, just after the first insurer lawsuit was filed.

With respect to the other issue—of the Department of Health and Human Services illegally diverting funds to the reinsurance program—it is still up to Congress to enforce the Government Accountability Office’s legal finding.

Basically, Congress needs to use the appropriations process to make the Department of Health and Human Services repay the Treasury by taking out of the department’s budget the amount that it illegally spent on the reinsurance program.

However, beyond these two items, there is also the third possibility of Obamacare supporters colluding with insurers to pressure Congress into extending the reinsurance program past its scheduled sunset at the end of 2016. That kind of “favoring-special-interests-over-taxpayers” mischief is most likely to occur during a “lame-duck” session following the elections before the new Congress and president are in place.

The idea of extending the reinsurance program is already being floated by Obamacare supports. The authors of a recent Commonwealth Fund paper recommended that “policymakers should consider extending the ACA’s [Affordable Care Act] reinsurance program.” Another prominent Obamacare supporter, Washington and Lee law professor Timothy Jost, offered that same recommendation back in June.

In yet another paper, published by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, two Georgetown University professors similarly suggest extending the reinsurance program, and even raise the possibly of making it permanent.

They go on to state, “Funds for the reinsurance pool would need to be, as they are currently, collected from individual market insurers, group market insurers, and self-funded plans.” Yet, that would mean converting what was a temporary (three-year) levy in the original law into an indefinite per-capita tax on over 150 million Americans enrolled in employer- or union-sponsored health insurance plans.

The architects of Obamacare correctly anticipated that individuals with expensive medical conditions would drop their existing coverage in favor of more heavily subsidized exchange coverage. However, they incorrectly assumed that would be a one-time phenomenon. Thus, they made the reinsurance program temporary (three years), with funding declining after the first year.

In reality, Obamacare’s concoction of badly designed “reforms” has turned the individual health insurance market into a dysfunctional money-loser for most health insurers—and the problems are getting worse, not better.

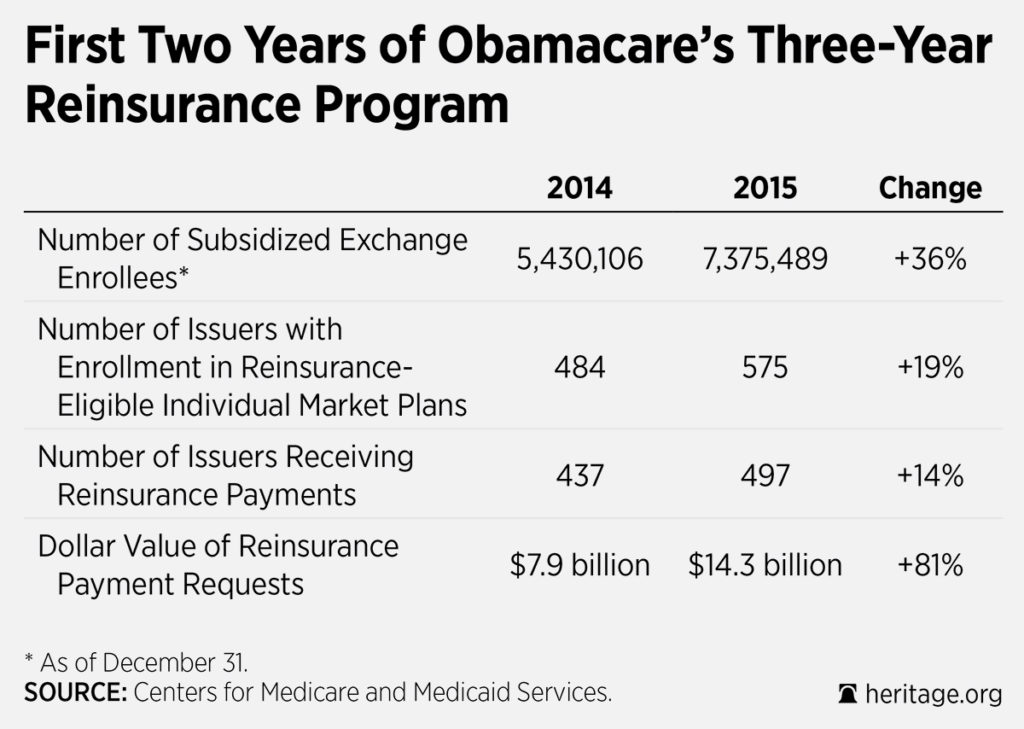

As the accompanying table shows, in the first two years of the program, reinsurance claims not only didn’t decline, but actually grew dramatically.

While enrollment grew by 36 percent, reinsurance claims jumped 81 percent. That means, contrary to expectations, that the Obamacare exchanges are attracting more, not fewer, high-cost enrollees.

Thus, it is not surprising that health insurers are lobbying for bailouts. But the same reason insurers want more bailouts is the same reason Congress shouldn’t hand them out—the situation is getting worse, not better.

Bailouts don’t fix the underlying problems. Only correcting Obamacare’s structural design flaws will do that. Rather than lobbying for bailouts, health insurers should be helping Congress design workable replacements for the Obamacare provisions that created the problems in the first place.