How the British Government Tries to Stop Youth From Becoming Terrorists

Josh Siegel /

Rashad Ali once belonged to an Islamic extremist group, but he now spends his days helping the British government prevent others from becoming radicalized.

His position makes him an easy target of criticism, from multiple angles.

“On the one hand, I get criticized from people in the Muslim community who see me as acting on behalf of the state and the authorities, and on the other hand I am criticized by those who are genuinely anti-Islam and see what I am doing—helping British Muslims reconcile their identity—as some kind of secret to plot to spread Islam,” Ali says.

As a Muslim growing up in Sheffield, an industrial city that carries what he calls an “anti-establishment” mentality, Ali says, he struggled finding his way. At 15 years old, he decided to join Hizb ut-Tahrir, a nonviolent Islamic political organization.

Today, Ali is 36. He and his consultancy firm, CENTRI, provide deradicalization interventions for those the government considers “vulnerable” to radicalization by Islamists. They are referred to him through a program called Prevent, the oldest and most ambitious domestic counterterrorism initiative in Europe.

The program also seeks to identify and intervene with Britons who may be susceptible to extremism promoted by both left-wing and right-wing political groups.

At a moment when many countries in the Western world, including the U.S. and France, are trying to develop tools to defend themselves against the threat of homegrown terrorism, Britain’s intensive approach is receiving heavy scrutiny at home.

With anxiety and division over terrorism, immigration, and religion at a fever pitch, some Britons criticize Prevent as a heavy-handed, bureaucratic strategy that stigmatizes Muslims. Supporters, though, consider the program a necessary, serious-minded solution that reduces the risks of all forms of extremism.

Perhaps most contentiously, Prevent includes a statutory requirement that Britons who are part of public institutions that serve youth also must protect them from becoming extremist.

“There aren’t many people who get involved in this work at this level,” Ali tells The Daily Signal in a phone interview. “But because I was involved in the other side for quite a long time, I’ve seen the damage that radical ideas can do to vulnerable people.”

He adds:

What you have to do is speak with parents of children who have been involved in these types of [terrorism] incidents. The one common thing they say is, ‘Why did no one help us? Why didn’t anyone do anything?’ So I don’t have the luxury of debating whether this program is necessary or not.

Backlash to ‘Mammoth Task’

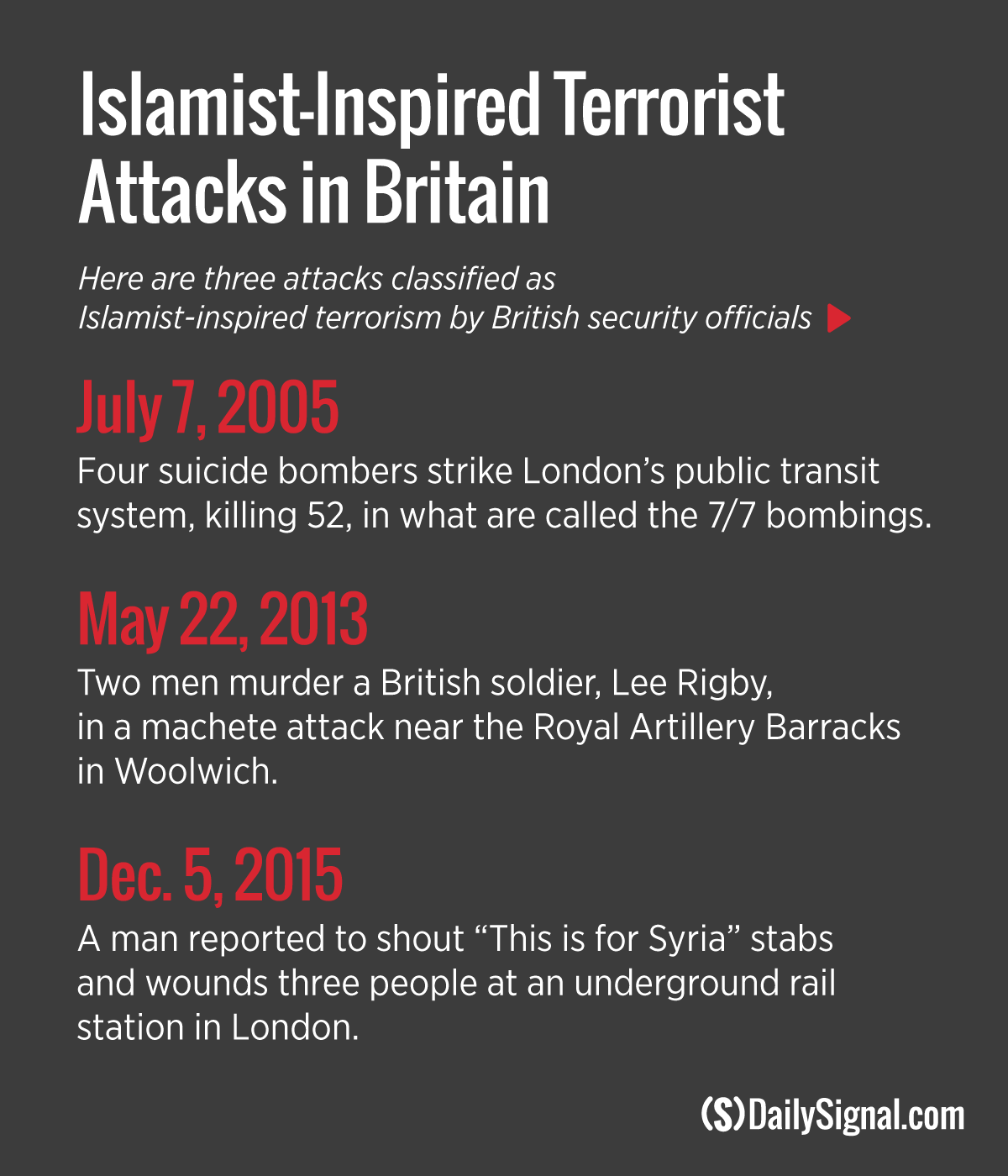

Britain has not suffered a major terrorist attack since the rise of the Islamic State, or ISIS, unlike the U.S., France, and Belgium. But the United Kingdom long has been an attractive target for terrorists.

British intelligence services, considered some of the best in the world, have foiled planned attacks before they happened.

In 2015, authorities made 35 percent more terrorism-related arrests in the United Kingdom than in 2010. About 800 individuals from Britain have traveled to Iraq and Syria to fight in the conflicts there. Among them: Mohammed Emwazi, a British Arab who notoriously beheaded multiple Americans and Britons before he was killed in a U.S. airstrike in November 2015.

About half of those who left Britain are estimated to have returned.

The British government currently designates the threat level of terrorism in the country as “severe,” meaning an attack is “highly likely.”

Long before the most recent threats, Britain maintained a comprehensive, preventive approach to counterterrorism, beginning its efforts shortly after the 2005 bombings by Islamist terrorists of London’s public transport network. That attack is commonly known as 7/7 for the month and day it occurred.

The Prevent program, one component of Britain’s overall strategy to fight terrorism, does not involve intelligence or police work, and few people, if any, who are referred to services through the program are arrested. Instead, Prevent is meant to help those who have shown early signs of extremism—before committing criminal acts—and have not demonstrated an imminent threat to do harm.

Indeed, the government intends for Prevent to complement a second element of Britain’s counterterrorism strategy, called Pursue, dedicated to detecting, prosecuting, and disrupting active plots against the homeland or British interests abroad.

The Prevent strategy has undergone different iterations. Its current form under Britain’s conservative government is especially controversial because its implementation is required by national law.

In July 2015, a section of Britain’s Counter-Terrorism and Security Act placed a mandated duty on certain public institutions—including schools, universities, hospitals, and prisons—to prevent those it interacts with from “being drawn into terrorism.”

Specifically, the British government teaches front-line staff at these institutions how to recognize the early signs of extremism and refer those they have concerns about to intervention services such as mentoring and mental health treatment.

The government’s Home Office, a department responsible for immigration and security, defines extremism as “the vocal or active opposition to our fundamental values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty, and the mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs.”

Since reporting became a legal requirement, referrals to the deradicalization program, known as Channel, have increased significantly. Almost 4,000 individuals were reported through the program in 2015—nearly three times more than the year before.

The Conservative Party made changes to the Prevent program.

It gave jurisdiction over the program to the Home Office, which new Prime Minister Theresa May formerly led. The government also became stricter about which community groups it funds to help implement the program, ruling out working with groups it considers to “oppose British values.”

The conservative British government led by Prime Minister Theresa May, center, has prioritized outreach to Muslims. (Photo: Andrew Parsons/Zuma Press/Newscom)

Investigations into earlier versions of Prevent showed the government gave money to nonviolent extremist groups just because they denounced terrorism.

In addition, the government vowed to broaden its focus to combat all forms of terrorism, including right-wing and left-wing extremism, with a particular focus on confronting the ideology that it considers to be the driver of violence.

Some civil liberties groups and Muslim community leaders say the recent legal requirement to report has made public workers overly cautious, causing them to make referrals that are inappropriate and without justification.

A July report on counter-extremism efforts by Parliament’s Home Affairs Committee notes that unions representing educators, including the National Association of Head Teachers, are concerned about a lack of “guidance, support, and training for schools.”

Other educators and local Muslim leaders testified that the reporting requirement, coupled with the targeted focus on ideology, stifles classroom debate and alienates Muslim students.

Mohammed Khaliel, a community leader, told The Daily Signal in an interview that some Muslims view Prevent as discriminatory.

“The [Prevent] program is meant to address the problem of people becoming extremist and causing harm to Muslim communities; however, the very program trying to achieve that can also alienate the community that it is required to assist, which makes the problem go underground and makes it worse,” Khaliel says.

Mohammed Khaliel, a Muslim community leader, says it’s vital that the British government engage people of his faith. (Photo: Courtesy of Mohammed Khaliel)

Khaliel, 50, who helps coordinate referrals to the Channel deradicalization program from a high school outside London, says he doesn’t believe Prevent is misguided altogether.

Indeed, he is passionate about creating stronger ties between Muslims and the wider society, and says government should have a role in that.

He is the founder of Islamix, an organization dedicated to building those ties, and frequently consults with law enforcement about how to engage with his community.

Khaliel refers to British police officers as “the best in the world” and he credits law enforcement for creating trusting conditions that encourage Muslims to share useful intelligence.

But he says the government risks alienating Muslims if it is too overbearing and not transparent enough about what it expects from those who cooperate with Prevent.

“My feeling is we definitely need to have some type of initiative that deals with this quite realistic problem,” Khaliel says of homegrown Islamist terrorism, adding:

Those who don’t think there is a problem are in denial. Prevent in its entirety is not all bad. However, it needs to be a combined effort of all entities. The government needs to listen to its communities. It’s a mammoth task, but if you sit together and try to dispel some of the misconceptions and mistrust between parties, then you are halfway to solving everything.

Supporters of Prevent argue the program exists as a vehicle to address various forms of extremism and terrorism, not just Islamic-inspired, and say it tailors services to individual needs.

“It’s not expected that every public sector staff member has a finely detailed, nuanced understanding of all the manifestations of extremism and how to respond to them,” says Hannah Stuart, a terrorism expert at the Henry Jackson Society, a British think tank.

“That would be impossible—most politicians don’t have that level of understanding,” Stuart adds in an interview with The Daily Signal. “But what Prevent is trying to do—building a capacity to integrate and teaching communities to be resilient—are the sort of things you don’t see happening much in places like France or Belgium. Britain has a structure in place to help people who may be vulnerable [to extremist influences], and that’s the nature of this work. It’s long term and meant to respond as threats evolve and change.”

The British government insists it remains committed to Prevent despite criticisms. It is currently reviewing the program as part of a broader reflection on counterterrorism strategy.

“The threat we face, particularly from Daesh [ISIS], is very real and we have all seen the devastating impact radicalization can have on individuals, families, and communities,” Security Minister Ben Wallace told The Daily Signal in an emailed statement, adding:

Prevent is about working with local communities to protect those who may be vulnerable to being targeted by extremists and terrorist recruiters. It is both challenging and vitally important work which we are committed to continuing—and many countries have looked to our model as they develop their own approach.

‘Here to Help the Community’

Those who help implement Prevent in local communities across Britain are sensitive to the complaints, and say they are eager to prove right the government’s approach and improve upon areas of concern.

William Baldet is a Prevent coordinator for the Midlands region who has worked with the program in all its previous forms for eight years. Baldet is motivated to help address a problem that he says touches everyone.

He grew up with a “strong moral compass,” he says, in a “loosely Christian” household in a rural area of the Midlands with a small Muslim population.

He found Muslims to be peaceful and no different than anybody else, Baldet says, and when terrorists increasingly began using Islam to justify violence, he felt inspired to help spread a countermessage.

“I did feel in those early days what made me stay the course was I wanted to do right by those Muslims who have no connection to extremist people or ideology, yet they are the ones being spat on in the streets of the U.K.,” Baldet, 44, tells The Daily Signal in an interview:

As a member of our community, I can’t stand by. I know it sounds like white privilege, and people may say who am I to help. But it’s all of our problem, isn’t it? When I say our community, it’s not about ‘Who are you to help the Muslims?’ It’s, ‘I’m here to help the community.’ It’s not the police and government long term that solves this problem. It’s got to be communities themselves.

William Baldet, a local coordinator of Britain’s Prevent counterterrorism program, says combating extremism is a challenge for all communities. (Photo: Courtesy of Pukaar News)

As a Prevent coordinator, Baldet represents a region deemed by the government to be at high risk for recruitment by extremists and terrorists.

He is tasked with developing a strategy designed to help those vulnerable to radicalization. The region he covers includes the city of Leicester, population 330,000, and four surrounding smaller towns and villages, for a total population of about 1 million.

Baldet says the local strategy must be approved by an oversight board comprised of representatives of various sectors including local government, mental health professionals, child safety services, probation and parole programs, prisons, schools, and universities.

He is employed by his local government, which receives Prevent funding from the national government.

Baldet spends many of his days interacting with Muslim religious and community leaders during visits to mosques and madrasas, trying to create local buy-in for the government’s program.

He also frequently spends time at outreach centers that work with vulnerable young people of any faith. He says the first case he worked on with Prevent involved a boy younger than 12 who was groomed for neo-Nazism by a grandfather. About 15 percent of interventions are connected with right-wing extremism.

“When people question if we are disproportionate toward focusing on one faith over the other, I say only so far as we deliver resources to where the greatest risk is,” Baldet says, adding:

As you get to more rural countryside areas, where there is long-standing, predominantly white communities, the threat is more far-right extremism. But in the inner cities is where you get more of the violent Islamist narrative. And right now, the greatest threat in the U.K. is Islamist recruiters. It’s terrorists [who are] targeting Muslim communities, not us.

Personal Approach

Rashad Ali, the Prevent interventionist and former nonviolent extremist, is one of several Muslim authority figures who provide mentoring to those considered vulnerable to radicalization.

While his deep knowledge of Islam, and his past, give Ali instant credibility to help others from similar backgrounds, he says each case he encounters is unique, so he takes an individualized approach.

“There are different things that motivate individuals to be attracted to extremism,” Ali says. “For some of them, it may well be religion, and how they interpret scripture. For others, it will be a personal grievance or experience. And you will also get individuals highly motivated by politics.”

He adds:

The fact I have been in a similar process of going in, and coming out, helps inform my understanding. But it’s also about having some understanding of human psychology. The majority of individuals who I work with are not bad people. Rather than telling them what they should think, I try to get them to see outside their particular worldview.

Many referrals to Ali come through mosque leaders he knows, he says, but those cases occur outside the Prevent structure since mosques are not public institutions and bound by the legal duty to report individuals of concern.

Referrals assigned to him through Prevent often originate in schools.

Every school in Britain has a staff member known as a safeguard lead, whose responsibility is to be the main resource for telling authorities about incidents related to the well-being of students. These concern not only extremism but issues long part of education, such as bullying, sexual harassment, and child abuse.

Though every region is different, the referral process typically goes like this:

After a school’s safeguard lead is made aware of a concern, usually from a teacher, a multi-agency team reviews the case and determines services to provide that student. The team consists of representatives from social services, law enforcement, health care, and other agencies.

If the case is related to extremism, the team refers the incident to the Channel panel, which similarly is made up of local leaders in government, policing, mental health, probation, and other sectors.

The panel determines whether a person’s susceptibility to radicalization is serious enough to warrant further attention, and if so, will decide what kind of intervention that individual requires. Intervention could consist of mentoring services similar to what Ali provides.

The student must agree voluntarily to participate in an intervention; support services also require approval by the student’s parent or guardian.

Baldet says few individuals decline offered services.

In the vast majority of cases, though, the panel declares referrals to it were inappropriate and not serious enough to warrant further action—a fact often cited by critics of the Prevent program.

In recent years, Channel panels found 80 percent of reports to be false alarms, according to data from the National Police Chiefs’ Council.

To some observers, this data point shows how difficult it is to predict who could become radicalized, and why it’s unrealistic to expect educators and others who interact with youth to know what to look for.

Quintan Wiktorowicz, a former senior adviser to the U.S. Embassy in London who established the State Department’s first embassy-based counter-radicalization program, says the young men and women attracted to ISIS’ brutal version of extremism often haven’t solidified their identities.

The path to extremism or terrorism is not as predictable as it was during the heyday of al-Qaeda, he says, when recruits usually were more versed in Islam and motivated by ideology.

“When people say we need to fight radical Islam, that applies to the support of al-Qaeda 10 years ago,” Wiktorowicz tells The Daily Signal in an interview. “I don’t think it’s a war of ideas anymore. It’s something different. It [radicalization] is being driven by other factors like identity and criminology more than ideology. You have had individuals who read ‘Islam for Dummies’ and went to ISIS.”

Wiktorowicz adds:

That’s good news and bad news. It’s good news if it’s not really about ideology, because that’s hard for the government to take on since we are not credible [to many Muslim youth]. So that means we need to think very seriously about what the drivers [of radicalization] are, and that may open up a series of tools that haven’t applied to counterterrorism as of yet.

‘It Should Be Our Duty’

Adam Whitlock, a senior teacher at Ark Burlington Danes Academy in west London, is his school’s primary contact for concerns related to extremism.

He leads religious studies at the school, which serves about 1,300 students 11 to 18 years old, 40 percent of whom are Muslim. The school itself is not faith-based. All students in Britain take classes in religious education, to learn of the world’s faiths.

Whitlock says he’s earned the trust of Muslim students by working hard to build relationships and empathizing with their experiences.

“We do have a handful of Muslim students that are quite vocal about mistrust of police and government,” Whitlock tells The Daily Signal in an interview. “But our Muslim students for the most part, because we are having open conversations regularly with them, they themselves will often condemn the terrorism going on in the Middle East and in this country when there are attacks and threats. You can see how much trust they have in the system, so together we can promote the right kind of Islam.”

That trust paid off four years ago, when Whitlock says he helped persuade one of his Muslim students, who was 15, from acting on radical Islamist ideology.

The student’s parents had expressed concerns to Whitlock that their son was watching videos of a radical imam online.

Whitlock reported the boy to Prevent’s Channel intervention team. But before he did, the teacher made an effort to talk through the student’s problems one-on-one.

“This student is very bright and well-read and he could argue about his beliefs all day,” Whitlock, 33 and a practicing Protestant, says. “It was clear he had a very one-track mind. I tried to give him the tools so he could pull down the beliefs he had. And that doesn’t work with arguing. It starts with me listening and slowly chipping away at his thoughts and getting him to realize what he is thinking is crazy. In the end, they hear their own voices more than yours.”

Once Whitlock connected the boy with the Prevent team, the panel of experts—with permission from the student and his parents—referred him to mentoring sessions with a Muslim counselor.

The young man is now a university student, pursuing a normal life without radical ambitions.

“I would say almost in every single one of these cases, there’s always an outside influence coming from a person, family member, social group, or even just the internet, because they are in a position at that age where they are still developing and growing their belief systems,” Whitlock says. “But if you can help them change themselves, it shows how fickle and vulnerable their minds can be. And it makes it worth what we are doing in reaching out to them and supporting them to help them see the world in a more moderate way.”

Whitlock has experienced the cost of not reaching a young person.

Last year, a male student who once attended Ark Burlington Danes Academy died overseas fighting with ISIS. Whitlock did not teach the student, a British citizen of Sudanese descent named Mahmoud Elsheikh, but knew of him.

The Prevent program was not as far along when Elsheikh was a student, Whitlock says, and faculty had not viewed him as a problem. He traveled to ISIS a year after leaving the school.

Afterward, Whitlock says, the Prevent team came to the school to teach faculty how to recognize early signs of attraction to extremism or terrorism.

At the start of the school year, Whitlock leads training of school staff, and every new teacher is exposed to his lessons.

“I think all educators have a duty to observe student behavior and report it when it becomes a concern and vulnerability for them,” Whitlock tells The Daily Signal in an interview. “Our main concern is the student’s well-being. Those are the people we ultimately care about. If we think anything will harm them, whether that’s extremism or anything else, it should be our duty to bring attention to it.

Whitlock adds of the student who joined ISIS: “I always think of him as a reason for why this is worth it. ”

Improving the Process

Sean Arbuthnot, a veteran policeman, spent the past three years working as a Prevent officer in Northamptonshire, a rural county between London and Birmingham.

The job required Arbuthnot to investigate referrals of possible radicalization to help determine if the persons met the threshold to be recommended for intervention assistance. It was much different than the traditional detective work he was accustomed to doing.

“It’s not what you think about with policing, where you want to get the bad guys,” Arbuthnot, 37, tells The Daily Signal in an interview. “In three years, I never made a single arrest. And that’s a mark of how successful it was. You are preventing them from going down the bad path in the first place. You want to keep people out of the criminal justice system. You don’t want to criminalize them.”

Despite the change in responsibilities, he chose to work in preventive counterterrorism because he thought he could use his community-building skills to tackle what he calls the biggest “challenge of our time.”

“To me, this is a moral responsibility to help us be better people, and look out for the most vulnerable people,” Arbuthnot says. “We, as a civil society, need to do our part in terms of combating extremism. This issue will be around for another generation at least. The police can’t do it themselves and the government can’t do it themselves.”

Arbuthnot, who is originally from Northern Ireland, grew to care so much about this responsibility that he decided to leave his post as Prevent officer earlier this year to try to improve the program from the outside.

Though his interactions with schools, colleges, health providers, and others involved with Prevent, he became frustrated by what he saw as an insufficient and unfocused level of training by the government.

Arbuthnot decided to launch his own private training service, with another former Prevent officer, to help public institutions realize the obligations of their reporting duty.

“It’s been difficult for the Home Office to come up with a one-size-fits-all approach that can be delivered by anybody because there are so many types of people who can be served by Prevent,” says Arbuthnot, who was raised Catholic but is not religious. He adds:

Training programs should be tailored differently to people depending on where they are. In this new, private role, I can deliver teaching to 50 to 100 people at a time each day from all walks of life. We are raising awareness with people who the police won’t necessarily reach, and helping to build resilience at a grassroots, local level.

Arbuthnot says too much of the government’s training occurs online, a forum that he considers superficial considering the intimacy of the responsibility. The government offers every public institution engaged with the program a standardized, basic introduction through an online workshop.

Arbuthnot argues the responsibility of public entities under Prevent is actually quite straightforward and not burdensome, if only the government would explain the process better.

Others share his concerns.

In an interview Thursday with BBC Radio, lawyer David Anderson—Britain’s independent reviewer of terrorism legislation—recommended reform of Prevent to make it more transparent about the results of interventions and connect more effectively with Muslims.

“It is frustrating for me to see a program whose ideals are so obviously good falling down on the delivery to the point where it is not trusted in the community where it principally applies,” Anderson said. “It may be effective. But people need to know that. And they need to believe that.”

He also called for an independent body to review the results of the Prevent program.

Arbuthnot contends that better communication, accountability, and consistent training would improve the effectiveness of referrals and create a fairer process for everybody.

“You will never be able to stop inappropriate referrals, just like you can’t stop inappropriate calls to police,” says Arbuthnot, who adds that people who are reported for no valid reason are not punished or publicly acknowledged. “I wouldn’t criticize anyone for making an honestly made referral,” he says. “I wouldn’t want anyone to have sleepless nights because they are worried about somebody, and that’s just not for extremism, but also any safeguarding issue. However, if you improve training and openness around the process, you encourage less and less inappropriate referrals.”

Arbuthnot and others involved with Prevent recognize the challenge in proving the program is doing what it’s intended to do—stop people from becoming extremists, and keep the homeland safe.

Yet they say they are making an impact.

“As far as measuring Prevent, you cannot say our work has prevented a terrorist attack because it’s hard to prove a negative and you simply don’t know,” Arbuthnot says. “But there is more and more anecdotal evidence that we are helping a person’s circumstances, and I know that I have personally deterred young people from traveling to Syria.”

Baldet, the Prevent coordinator who remains with the program, vows to continue his work for the sake of the British people.

“The criticisms are frustrating, not debilitating, and they don’t stop us from doing what we do,” Baldet says, adding:

It’s a genuinely exhausting job, it messes with your head, and you take it home with you 24/7. But the other day, I looked to my little daughter, who is 10 months old, and I thought, ‘You are the reason I am doing this. I don’t want my world I’m living in to be your world.’