Meet Native Americans Fighting Obama’s Push to Conserve Public Land

Josh Siegel /

The latest front in a debate over the reach of U.S. control of federal land is a 1.9 million-acre retreat of mesas and canyons located in Utah’s poorest county.

The stakes are large for this remote land, which President Barack Obama is considering designating as a national monument, in his continued pursuit of being the most prolific conservationist to ever occupy the White House.

But for the local Native Americans who live near the land—known to them as Bears Ears—and depend on it for sustenance and cultural tradition, the debate over how to best preserve it feels smaller, but no less important.

“Bears Ears has a lot of meaning to me,” said Marie Holliday, a 72-year-old resident of Monument Valley in Utah’s San Juan County who belongs to the Navajo tribe.

Added Holliday, in an interview with The Daily Signal:

Our people have used the land for generations. With my grandmother before she died, we would go across the San Juan River to graze [livestock]. In the fall, people start to go out there to get firewood to heat their homes for winter. We use the herbal plants that grow there to heal sickness. A lot of our ancestral ruins are buried there. It really is a beautiful place.

Obama’s Conservation Drive

Holliday does not support the work of a coalition of tribes—including the national body of her own, Navajo Nation—that is advocating for Obama to use his executive power under the Antiquities Act of 1906 to make Bears Ears a national monument.

Whereas supporters of a monument see it as a way to best protect Bears Ears from looting, mining, and drilling—and a tourist boon for the area’s struggling economy—local Native Americans who oppose it don’t trust the federal government to look out for their interests.

The 1.9 million acres in southeastern Utah defined in the proposal by the coalition of tribes are public lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management, U.S. Forest Service, and National Park Service.

“I hope our people can still enjoy Bears Ears,” Holliday said. “But I fear with a monument, there will be more restrictions, and we won’t have that opportunity, especially our Indian people, our Navajo people. We are always being cut off somewhere, and we don’t really trust the federal government. That’s the way we are. We want to continue to use it like the way it is.”

The Obama administration’s consideration of Bears Ears as a national monument shares characteristics with the president’s recent use of the Antiquities Act.

On Aug. 24, siding with conservationists over the opposition of some residents and local officials, Obama designated more than 87,500 acres in Maine as a national monument.

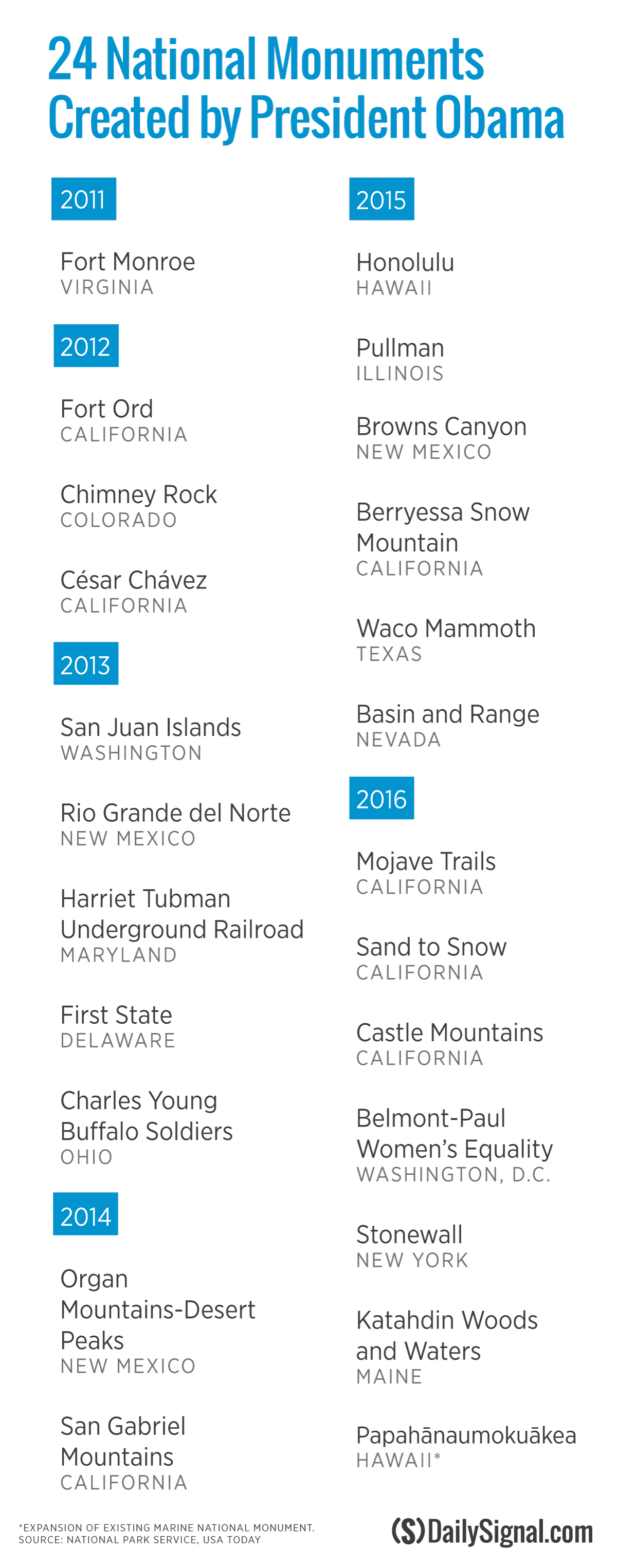

Obama has created 23 national monuments, in addition to expanding an already existing one, more than any previous president.

In Utah, the Bears Ears monument proposal also lacks local backing.

Among opponents are the San Juan County Commission; Utah Gov. Gary Herbert, a Republican; the GOP-controlled state legislature; and the state’s congressional representatives.

But the tribal coalition of Navajos, Zunis, Hopis, Utes, and Ute Mountain Utes that is pushing for the monument views itself as representative of local interests. As part of its proposal, the coalition asks to jointly manage the land with the government.

Who’s Protecting the Land

“To put it plainly and bluntly, the people elect us to sit in these positions, and there is no way an elected leader would ever advocate for lack of access for its own people,” said Regina Lopez-Whiteskunk, councilwoman for the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe and co-chairwoman of the Bears Ears Inter-Tribal Coalition.

Lopez-Whiteskunk, in an interview with The Daily Signal, added:

We believe we need to protect that access to the land, but do it in a respectable and responsible manner. We understand what it’s like to live out there. We’ve survived it. To think any tribal leader would cut off the supply to herbs, and firewood, and the capacity to say their prayers, is simply absurd.

In addition to the coalition’s tribal representation, it also gets support from major conservation groups and nature advocates.

According to a report in a local newspaper, Deseret News Utah, the campaign for the monument has been granted $20 million in donations from two philanthropic groups — the Hewlett and Packard foundations — that cite environmental protections as a focus for the grants they award.

The Conservation Lands Foundation also supports the coalition’s proposal, the newspaper said.

Native Americans who live near the remote mesas and canyons of Bears Ears depend on it for sustenance and cultural tradition. (Photo courtesy of Sutherland Institute)

Lopez-Whiteskunk, 47, is a college-educated resident of Towaoc, Colorado, the headquarters of the Ute Mountain Ute Tribe to which she belongs, located about an hour-and-a-half drive from Bears Ears.

Using her platform “as someone lucky enough to speak for my people,” Lopez-Whiteskunk said it’s appropriate to collaborate with outside groups if it helps accomplish the coalition’s goal of making Bears Ears a national monument.

“When people say outsiders are coming in and we are backed by environmentalists, I say, ‘Heck, yeah, we are,’” Lopez-Whiteskunk told The Daily Signal, adding:

There’s nothing wrong with that. It’s just some people think Native Americans are not intelligent enough to seek resources, and seek out organizations and experts. We can and we do. I am a Native American who’s educated and I have the ability to research and utilize tools in a manner any movement would utilize. So I feel strongly that this initiative has the correct spirit and the right intent.

‘Trying to Work Together’

As the Obama administration considers the tribal coalition’s request, Utah’s representatives in Congress are planning their own method to preserve Bears Ears.

In July, Reps. Rob Bishop and Jason Chaffetz, both Republicans, introduced the Utah Public Lands Initiative.

The massive public lands bill includes a provision that would conserve less of Bears Ears—1.4 million acres instead of 1.9 million acres—and also would allow energy development in certain areas.

Bishop, chairman of the House Natural Resources Committee, told The Daily Signal in an interview that his panel will mark up the legislation at the end of the month.

“Intellectually, creating a monument is a legislative function and should never have been an executive function,” @RepRobBishop says.

The committee was scheduled to hold a hearing on it Wednesday morning. A floor vote wouldn’t come until after the presidential election, Bishop said.

His measure is opposed by environmental groups and the tribal coalition, who say it does not significantly protect natural resources.

The Fallen Roof Ruin is contained in the 1.9 million-acre Bears Ears area proposed for a national monument in southeastern Utah. (Photo: Fotofeeling/Westend61/Newscom)

Bishop has made a congressional career fighting for local land rights. About 65 percent of Utah’s land is controlled by the federal government. The federal government owns 28 percent of all U.S. land, according to the Interior Department.

Bishop argues that executive action by the president would create ill will among locals who are split about what to do.

“If the president acts, he messes up what has been three years of trying to work together,” Bishop said, adding:

“He can’t claim to have the local support to do it. Our plan is good and theirs sucks. Intellectually, creating a monument is a legislative function and should never have been an executive function. It has also become at least curious, if not downright hypocritical, why the president is considering doing this now as he is leaving office and is no longer accountable to explain why he did things.”

‘Won’t Have a Home No More’

No matter the path to protect Bears Ears, uniting the tribes is a challenge.

Jovanii Nez belongs to Descendants of K’aayelii, a group that considers itself the original inhabitants of the area in and around Bears Ears, and heirs to the land.

Nez, 43, says the group’s members are relatives of Hastii K’aayelii, a Navajo leader whose followers never surrendered to the federal government during the American-Indian Wars.

In 1933, the group says, the government relocated its members against their will from Bears Ears to an area of the Navajo reservation known as the Aneth Extension.

Descendants of K’aayelii opposes both the monument and the congressional approach, Nez told The Daily Signal in an interview.

“This discussion over the monument, and what to do about Bears Ears, has elevated our story but no one wants to hear it,” Nez said. “All that is keeping us alive is our passion for our homeland. We want a place where we know who we are. With a monument, we won’t have a home no more.”