The Popular Narrative About Financial Deregulation Is Wrong

Norbert Michel / Tamara Skinner /

Americans are being fed a false narrative.

As the story goes, in 1999, Congress repealed the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act. The financial sector was free from the watchful eye of federal regulators. Then in 2000, Congress deregulated derivatives, and all of this deregulation resulted in the financial mess known as the Great Recession of 2008.

That’s still a popular tale, but it’s dead wrong.

By every objective metric, there has been no substantial reduction in U.S. financial regulations during the past 100-plus years. Most financial market activity has taken place under the careful supervision of the federal government since at least the 1930s, and Congress has continually expanded the number and nature of financial sector regulations.

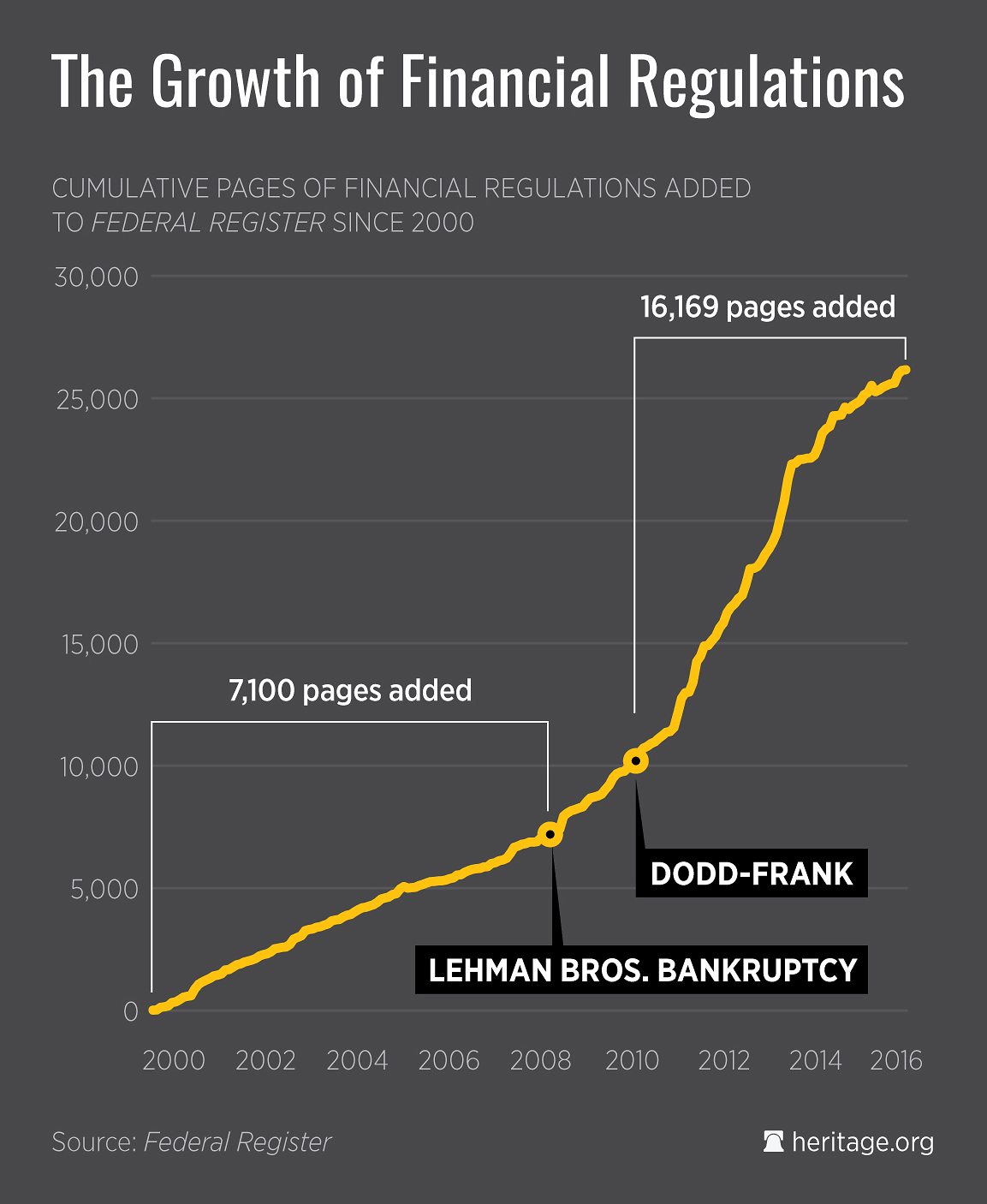

Leading up to 2008, the rate of new financial regulations remained broadly consistent with the long-term trend. In other words, financial regulations steadily increased. They did not decrease. The trend on Chart 1 is unmistakable: the volume of financial regulations climbed from 1999 through the 2008 crisis.

From the supposed deregulation in 1999/2000, up until the Lehman Brothers failure in 2008, financial regulators issued 7,100 pages of regulations for more than 800 separate rules. Of course, this figure pales in comparison to what happened after Congress passed Dodd-Frank in 2010.

Thanks mostly to Dodd-Frank, financial regulators issued more than 16,000 pages of regulation between July 2010 and July 2016.

That’s a clear escalation, but the larger point is that there really was no deregulation prior to Dodd-Frank. The overall numbers support this theme, as does a close look at the examples typically cited as proof of deregulation.

>>> 7 Key Provisions of the Dodd-Frank Bill

For instance, the 1999 Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act supposedly repealed Glass-Steagall, the 1933 law that separated commercial and investment banking. In reality, the 1999 reform merely repealed two of the four sets of restrictions that Glass-Steagall imposed, and it even added five unrelated titles that, in most cases, increased financial regulations.

It is true that the passage of the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act meant that commercial and investment banks could legally affiliate. However, allowing two different types of financial entities to affiliate remains far from allowing the financial sector to engage in unregulated activity. Both investment banks and commercial banks remained separate legal entities regulated by their respective federal regulators.

Another supposed example of deregulation is the passage of the 2000 Commodity Futures Modernization Act. This law is blamed for preventing the Commodity Futures Trading Commission from regulating over-the-counter derivatives, but the commission didn’t regulate over-the-counter derivatives prior to the act’s passage.

A central purpose of the 2000 law was to clarify which regulator would oversee single stock futures contracts, not to lessen the Commodity Futures Trading Commission’s regulatory role. And the record clearly shows that the bulk of the over-the-counter derivatives market was still regulated by federal banking regulators.

>>> The Myth That Regulation Can Stop a Financial Crisis

Deregulation establishes a market where government agencies have no say in the kinds of products and services people can legally produce and purchase. There’s no doubt the rules governing the financial sector have changed in nature over time, but the financial sector has never been deregulated. The 1999 and 2000 reforms represent examples of changes in the regulatory framework before the financial crisis, not the absence of one.

Yet, the myth of deregulation continues to be used as a justification for continuous increases in federal micromanagement of banks and other financial institutions. Sadly, increases in this type of regulation led to the crisis in the first place.