16 Obamacare Co-Ops Collapsed. Here’s How the Rest Are Faring.

Melissa Quinn /

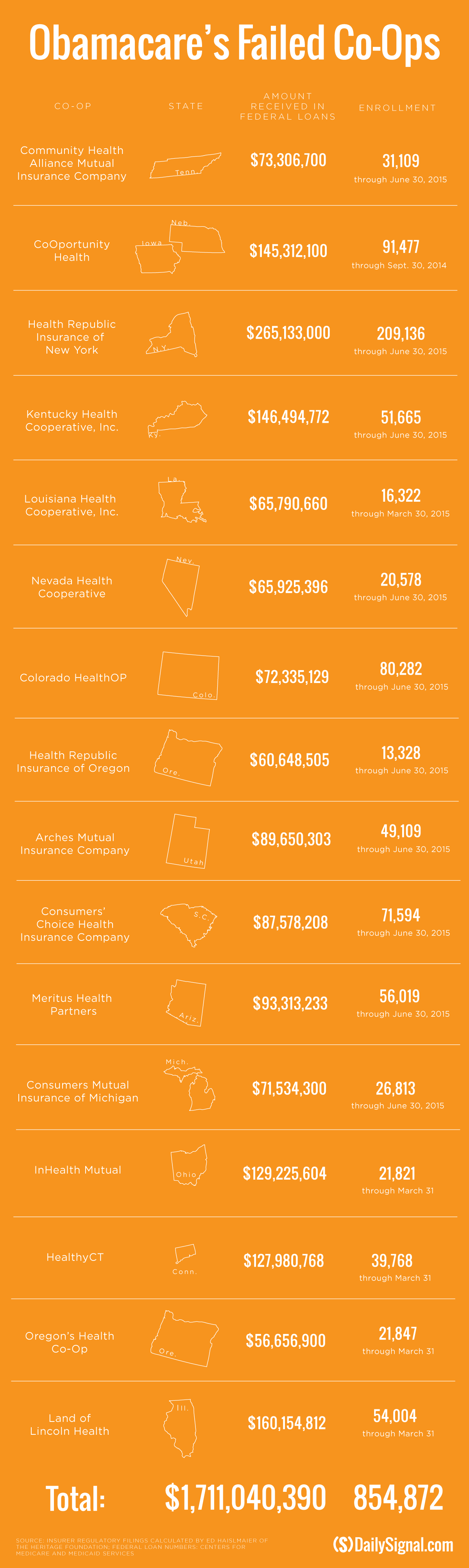

Since Obamacare’s rollout in the fall of 2013, 16 co-ops that launched with money from the federal government have collapsed.

The co-ops, or consumer operated and oriented plans, were started under the Affordable Care Act as a way to boost competition among insurers and expand the number of health insurance companies available to consumers living in rural areas.

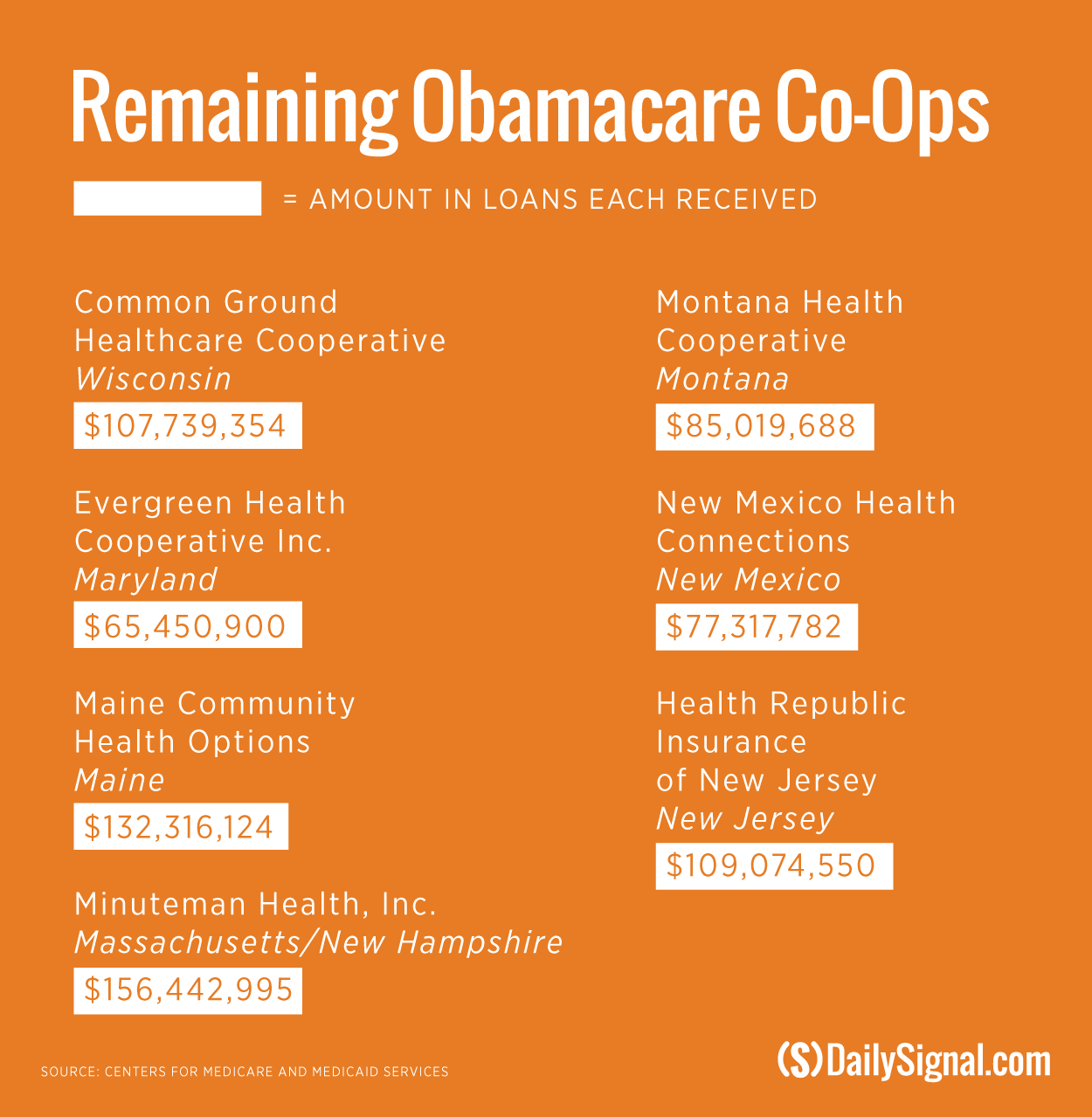

Now, just seven co-ops—Wisconsin’s Common Ground Healthcare Cooperative; Maryland’s Evergreen Health Cooperative; Maine Community Health Options; Massachusetts’ Minuteman Health; Montana Health Cooperative; New Mexico Health Connections; and Health Republic Insurance of New Jersey—remain.

Despite the grim financial footing from previous years, health care experts agree that it’s likely some—though not all—co-ops may remain standing for at least a few more years.

“I definitely think there are some co-ops that have seemed to have relative success in the market,” Caroline Pearson, a senior vice president at Avalere Health, told The Daily Signal. “I think we will have some surviving co-ops a couple years from now, but I can’t promise we won’t have a handful more that may fail over time.”

But for the seven co-ops left to survive, Pearson warned they will have to increase the cost of their premiums, especially since many of the nonprofit insurers kept the costs down during the beginning years of Obamacare’s implementation to attract customers.

“The big issue for the co-ops is getting the pricing right,” she said. “They really need to make sure they’re accurately assessing the medical risk of the exchange enrollees and pricing in such a way they can cover those costs.”

“I think there was very aggressive pricing strategies by many carriers in the first few years of the exchanges to try to win enrollment, and that’s really resulted in big losses for most of them,” Pearson continued.

Struggling to Make Money

The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services awarded $2.4 billion to 23 co-ops that were eventually created. However, the majority of the co-ops struggled to turn a profit, resulting in the collapse of 16 of the original 23 that received $1.5 billion in startup and solvency loans.

Now, with just seven co-ops remaining, regulatory filings show that many ended 2015 in the red.

Maine Community Health Options ended up losing money in 2015 after having a successful 2014.

The Maine co-op was the only one to make money in 2014 and hit its enrollment targets. But by the end of 2015, Maine Community Health Options’ finances took a turn for the worse and the co-op lost $74 million.

Already, regulatory filings for the first three months of 2016 show Maine Community Health Options posting more than $8 million in losses.

Officials with Maine Community Health Options did not return The Daily Signal’s request for comment.

Pearson said the Maine co-ops’ early success can be attributed to the state’s insurance market.

“The advantage of Maine is it is a relatively noncompetitive, or less competitive market,” she said. “It makes it easier for co-ops to enter the market and win market share because there aren’t so many entrenched companies.”

Wisconsin’s co-op, Common Ground Healthcare Cooperative, initially exceeded its enrollment projections in both 2014 and 2015.

However, the co-op ended up losing $43.2 million last year, according to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

For the first three months of 2016, Common Ground Healthcare Cooperative reported losses of $4.7 million, according to regulatory filings.

Thomas Miller, a resident fellow at the American Enterprise Institute who is an expert in health policy, said each of the seven remaining co-ops have “warning indicators” leading up to when, and if, they fail.

“As a general rule, this has already been the case with the ones that have failed to a large extent, usually the ones that grew the fastest and were the biggest were the ones that had the most problems,” he told The Daily Signal.

Miller specifically referenced the Health Republic of New Jersey, which made money in the first nine months of 2015, as an example of a co-op that grew quickly but shows warning signs of collapsing.

The co-op said it lost $17.6 million at the end of 2015 and is facing a $46.3 million payment to the government through the risk adjustment program, which was designed to spread risk among insurers.

To the contrary, Miller pointed to Maryland’s Evergreen Health and New Mexico Health Connections as two co-ops that could live on for a few more years.

“If you’re small, you can sometimes survive because the magnitude of your losses aren’t to the extent that the state insurance commissioner feels like, ‘Oh my gosh, this is really going to be bad for us and we really have to pull out before the open enrollment season,’” he said.

Still, Miller said it would be difficult for the co-ops that have been hemorrhaging money consistently over the years to recover.

“When they’re bleeding, they keep bleeding, and they continue bleeding, and at some point you have to cart them away,” he said.

Weathering the Years

Since Obamacare’s implementation, it’s not only co-ops that have struggled to make money.

Oscar, a startup insurance company serving New York and New Jersey that launched in 2012, lost $105 million in 2015.

Additionally, UnitedHealth Group CEO Stephen Hemsley said the company expects to lose more than $1 billion from its exchange business—$650 million in 2016 and $475 million in 2015.

The company, which is the nation’s largest insurer, decided to pull out of at least 26 of the 34 exchanges it offered coverage on last year after warning the marketplaces were a risky investment.

And Health Care Service Corporation, which operates Blue Cross Blue Shield plans in five states, reported losses totaling $65.9 million in 2015. The company lost $281.9 million in 2014.

Despite across-the-board losses for insurers of all sizes, both startups and established insurance companies have been able to remain afloat while the majority of the co-ops collapsed

“The benefit that these co-ops didn’t have, in addition to just fiscal reserves, was a diversity of markets they’re participating in,” Pearson said. “Lots of exchange plans have financial difficulty, but they could rely on their broad book of business to weather the initial years of challenge. Co-ops haven’t had that chance.”

In addition to increasing the cost of their premiums to compensate for their beginning years of enrollment, Pearson said the co-ops may also need to bump prices up to prepare for the end of the risk corridor and reinsurance programs, which were put in place until the end of this year.

The risk corridor and reinsurance programs are two of the “three R’s”—risk adjustment being the third—designed to spread risk among insurance companies enrolling consumers through the exchanges.

The co-ops received less money than they initially anticipated last year under Obamacare’s risk corridor program, which resulted in the collapse of at least five co-ops and a $5 billion class action lawsuit filed by Health Republic Insurance of Oregon, one of the state’s co-ops.

The reinsurance program, meanwhile, has helped the co-ops, albeit marginally. According to data released by the Department of Health and Human Services last month, the seven remaining co-ops could collectively receive $132.3 million in payments from the reinsurance program.

But with the end of the reinsurance program coming at the end of the year, the additional infusion of cash to the co-ops will go with it.

“The risk corridor, everybody has sort of already written off,” Pearson said, “but the lack of reinsurance is a challenge, especially for small plans and again sort of underscores the need for a big rate bump.”

Still, Miller said even if the co-ops raise their premiums, it’s unlikely the remaining seven will be able to turn their businesses around.

“When you’ve got a terminal illness, it is going to catch up eventually. Whether some can go into remission or basically string it along for a stretch of time, we always get these periodic predictions that, ‘Oh, if we just have next year it’ll be different,’” he said. “There’s just not something on the horizon. There’s just not some other approach that seems viable as to how they get out of the box they’re already in.”