25 Years Later, How Clarence Thomas Has Transformed the Supreme Court

Philip Wegmann /

When the Senate confirmed Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court in the fall of 1991, he was still new to the flowing black robes that cloak federal magistrates.

A rookie justice on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit, Thomas had served as a judge only since March 1990. Still raw from a bruising, 107-day confirmation process that wrapped up at the end of October 1991, Thomas had only a few weeks to prepare to hear cases that November.

“The easiest thing in the world under the circumstances would just be to go along to get along. He didn’t,” remembers Gregory Katsas, now a partner at Jones Day law firm and one of Thomas’ original cadre of clerks.

Instead, in an early episode that would become a trademark over the course of his career, the newest member of the court split with the other eight justices to write three solo dissents on complex and controversial cases.

Twenty-five years ago today—on July 1, 1991—President George H.W. Bush nominated Thomas to the high court. His subsequent independence and consistent judicial philosophy have endeared him to conservatives, earned the grudging respect of liberals, and helped transform the court.

Recent reports that Thomas planned to retire after a quarter-century on the court rocked the legal world. President Barack Obama already has nominated appellate judge Merrick Garland to take the seat vacated by the death of Justice Antonin Scalia. If Thomas retired, the ideological balance of the bench would tip and the court could shift course permanently.

But those close to the 68-year-old jurist dismiss the retirement rumors as groundless.

“I feel like we’re at halftime at a football game,” says John Yoo, a Berkeley Law professor and former Thomas clerk. “We can look back at how his performance has been in the first half, but we really care about the second half and if his team is going to win.”

And by all accounts, Thomas has had a productive first half.

Clarence Thomas ponders questions from members of the Senate Judiciary committee during his confirmation hearings in 1991. (Photo: Mark Reinstein/Zuma Press/Newscom)

His career has been marked by a consistent drive to advance the judicial philosophy of originalism, a principle that requires interpreting the text of the Constitution within the bounds of how it would have been understood 229 years ago.

That philosophy often places Thomas in the minority and has prompted some of his most provocative written dissents on issues such as abortion, guns, and voting rights.

For conservatives, his jurisprudence is a refreshing cause célèbre.

“He looks to how the Constitution was understood at the time of the ratification. He goes to first principles,” John Eastman, a Chapman University law professor and former Thomas clerk told the Los Angeles Times. “He is willing to challenge precedents that deviate from the original understanding.”

Liberal constitutional scholars see a dangerous threat to progress in his judicial philosophy.

“In 25 years on the court, Justice Thomas has shown himself to be very conservative and more willing to radically change the law than his colleagues,” said Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the University of California, Irvine Law School.

Either way, the justice doesn’t make much of criticism or attempts to catalog his judicial philosophy.

“I don’t put myself in a category. Maybe I am labeled as an originalist or something, but it’s not my Constitution to play around with,” Thomas told The Wall Street Journal in 2008. “I don’t feel I have any particular right to put my gloss on your Constitution. My job is simply to interpret it.”

And Thomas prefers to offer his jurisprudence on paper, not out loud. While his colleagues interrupt lawyers during oral arguments and pepper them with questions, he sits quietly—sometimes for years. When he does break his silence, it’s breaking news.

Correspondents rushed out of the court in February to report that Thomas finally had ended a decade of silence by pressing a government lawyer on some claims about the legality of limiting gun ownership.

His silence has led to significant speculation.

Some argue that Thomas is shy by nature. For proof, they point to passages in his memoir, “My Grandfather’s Son,” where he wrote that he never asked questions in college or law school. Others contend that Thomas stays quiet as a simple courtesy to lawyers.

Timothy R. Johnson, a politics professor at the University of Minnesota, has made an academic study of the muted justice. He says no other judge in modern history has maintained his silence as long.

While the justice is quiet in court, Johnson notes that Thomas is often chatty in person, emblematic of a biography made up of contrasts.

Thomas grew up in Pin Point, Georgia, during the height of Jim Crow-era racism. The son of a single mother, Thomas was raised by his grandfather, who he remembers as “the greatest man I have ever known.”

He credits his mother’s father for instilling in him self-reliance and the value of work, virtues that would take him from the Deep South to Yale Law School, and finally the Supreme Court.

Those close to Thomas say that the dramatic rise hasn’t led to elitism or snobbery, though. The justice who remains silent in court, his friends and former clerks say, has a gregarious laugh and an unexpected everyman quality.

“He knows everyone down to the janitors and the elevator operators in the court,” says Carrie Severino, a former clerk who is now chief counsel and policy director of the Judicial Crisis Network.

And while Justice Anthony Kennedy takes trips to Salzburg, Austria, and Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ruth Bader Ginsburg travel to Florence, Italy, Thomas prefers the U.S. interstate highway system. When he’s out of chambers, the conservative justice road-trips in a 40-foot RV, regularly spending nights in Wal-Mart parking lots.

The soft-spoken and private justice was thrust back into the public eye earlier this year when HBO released a made-for-TV movie chronicling the 1991 battle over his confirmation.

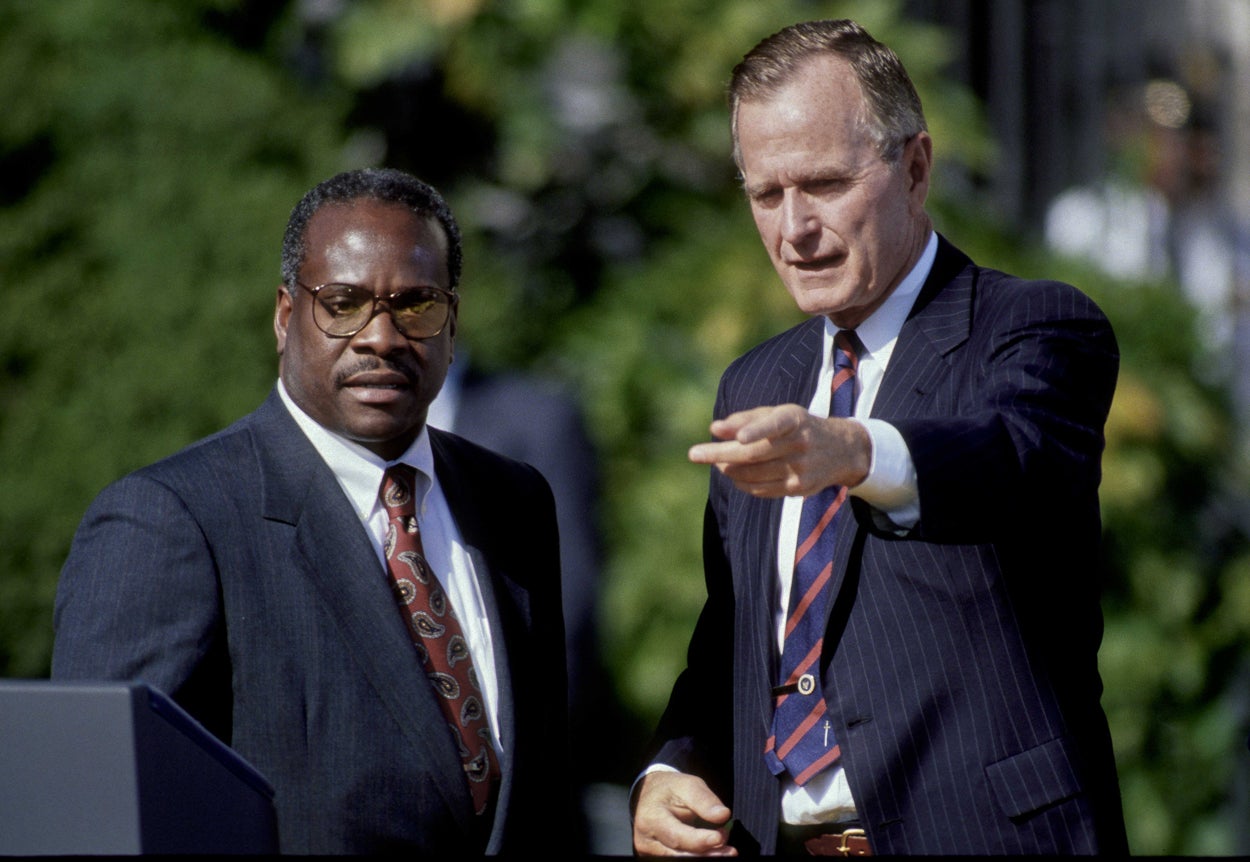

President George H.W. Bush with Clarence Thomas after he was sworn in as a Supreme Court justice. (Photo: Mark Reinstein/Zuma Press/Newscom)

The 107-day political struggle grew fierce when Democrats on the Senate Judiciary Committee accused Thomas of sexually harassing a former legal aide, Anita Hill. In the televised proceedings, Thomas accused the committee of conducting “a high-tech lynching.”

Thomas was confirmed by a vote of 52-48, after one of the most bitter judicial confirmation battles in modern history.

Those close to him remark that Thomas doesn’t display scars from the experience. That forgiving attitude was on full display earlier this May during a commencement address at Hillsdale College, a small liberal arts school in Michigan.

“As you go through life, try to be that person whose actions teach others how to be better people and better citizens,” Thomas told graduates during a rare public appearance.

That perspective will keep Thomas on the court, his former clerks say, because Thomas believes he still has more to contribute.

After the Feb. 13 death of fellow conservative Scalia, and high-profile losses last week in decisions upholding affirmative action and striking down abortion safety standards, some predict the end of the court’s conservative era.

“The more he might lose some of these issues, the more determined it’s going to make him to stay on the court,” Yoo, the Berkeley Law professor, says. “He feels it’s his job, his purpose in life to continue to stand up for these principles even more so if they become unpopular.”