Is It Time for Criminal Justice Reform? 2 Law Enforcement Groups Are at Odds

Josh Siegel /

While the unusual coalition of President Barack Obama and conservative groups hold out hope for the chance at what they call the most meaningful reform to criminal sentencing laws in a generation, frontline law enforcement officials are debating what the changes would mean for their communities.

Steven Cook, whose organization represents more than 5,500 assistant United States attorneys, believes Congress’ attempts to reduce prison sentences for certain low-level offenders will “substantially harm” law enforcement’s ability to “dismantle and disrupt drug trafficking organizations.”

William Fitzpatrick, the president of the official body representing state-level district attorneys across the U.S., views the issue differently, recently writing to congressional leaders that a Senate plan to reduce sentences for drug crimes allows “lower level offenders a chance for redemption.”

Cook and Fitzpatrick are two veteran law enforcement officials with vastly different jobs, but they have outsized roles in a debate over criminal justice reform with high stakes for the people they represent—not to mention the thousands of offenders who could benefit from changes to sentencing laws.

Fitzpatrick made headlines late last month when he authored a letter—on behalf of the National District Attorneys Association—to Senate leaders Mitch McConnell, R-Ky., and Harry Reid, D-Nev., expressing support for compromise legislation meant to reduce mandatory minimum sentences for low-level drug offenders.

That endorsement has encouraged other law enforcement groups to get on board, with both the International Association of Chiefs of Police and Major County Sheriffs’ Association announcing their support last week.

The revised legislation, written by Democrats and Republicans in the Senate Judiciary Committee, was tinkered with to win support from some skeptical law-and-order conservatives, who worried the bill would free felons who they consider to have violent criminal records.

The blessing from Fitzpatrick’s group seemed to have a dual effect of signaling to on-the-fence members that they need not worry.

“It’s been a process, and we’ve been vocally opposed to previous iterations of this, but the new legislation was worked on with more care, and is pro-law enforcement,” Fitzpatrick told The Daily Signal. “It really reflects things we’ve been doing at the state level for quite a while. A lot of states have significantly reduced their prison populations and crime rates as well.”

But Cook, and his National Association of Assistant U.S. Attorneys, remain opposed to the legislation, and he and the organization have the ear of still skeptical lawmakers like Sens. Tom Cotton, R-Ark.; Jeff Sessions, R-Ala.; and David Perdue, R-Ga.

“The notion we should save the American people money by releasing these repeat drug traffickers—and to take tools away from prosecutors needed to successfully prosecute them—is a breach of the fundamental responsibility that the federal government has to protect its citizens,” Cook told The Daily Signal.

Cook and Fitzpatrick know each other well, and have been in frequent communication about their positions on the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act, as the Senate’s legislation is known (although Cook says he was “very surprised” when Fitzpatrick endorsed the new bill).

Cook has served as an assistant U.S. attorney in the Eastern District of Tennessee for the last 29 years.

Fitzpatrick is the district attorney for Onondaga County in New York, a position he’s held for 24 years.

McConnell is ultimately responsible for deciding whether to allow the full Senate to vote on the bill.

In weighing his decision, McConnell is no doubt considering both sides of the argument communicated by Cook and Fitzpatrick.

As most compromises go, the legislation’s actual provisions are relatively modest.

The bill aims to reduce certain mandatory minimum prison sentences created in the 1980s and ’90s during the war on drugs, which are laws that require binding prison terms of a particular length, and designed to promote consistency in punishment. Critics charge these laws have proven to be inflexible, and, by limiting judge’s discretion to rule on the specifics of a case, have led to unfair punishments for lesser offenders.

“The number one priority of the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act is the promotion of public safety,” Sen. Mike Lee, R-Utah, a bill sponsor, told The Daily Signal. “Our criminal justice system is undermined when punishment delivered by the government does not fit the crime. Our bill better protects the American people by bringing balance back to federal sentencing.”

Sponsors of the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act include Republican Sens. John Cornyn of Texas, Mike Lee of Utah, and Chuck Grassley of Iowa. (Photo: Ron Sachs/CNP/Polaris/Newscom)

The bill, for example, would reduce the mandatory prison sentence required for drug offenders with two or more “serious violent felony” or “serious drug felony” convictions from life without parole, to 25 years. The bill’s authors adjusted this provision, and others, so that it does not allow violent offenders from being able to petition a judge for a retroactive early release.

“To say a third-time drug offender gets 25 years instead of life, is that going to impact public safety?” Fitzpatrick said. “Not in my judgment. If you are lucky, you get 75 years on planet Earth. If you take a third of a person’s life away from him or her, that is not what I would call a slap on the wrist. In this society, we can survive safely in giving someone 25 to 30 years as opposed to life.”

In addition to reducing required prison terms, the bill expands the circumstances under which a judge can use his discretion not to sentence an offender to a mandatory minimum.

Notably, the new bill does not include a provision contained in the original legislation that would have reduced the penalty for repeat drug offenders who had been in possession of a firearm.

Still, for people who view drug trafficking as an inherently violent crime, as Cook does, the reform would reduce the punishment for offenders who have done more than possess and use drugs.

“We are not prosecuting drug users in federal court,” Cook said. “This whole notion of low-level nonviolent drug offenders is wrong because that’s not who is coming into federal prison. We are dealing with dismantling large drug trafficking organizations.”

Cook is right that almost all federal drug offenders are sentenced for drug trafficking (last year, fewer than 1 percent were sentenced for simple possession.)

Yet proponents of reform argue that there are degrees of trafficking, and that most offenders are not primary dealers or “kingpins” who mandatory minimums are supposed to punish.

According to Families Against Mandatory Minimums, a nonprofit advocating for sentencing reform, 92 percent of the 20,600 federal drug offenders sentenced in fiscal year 2015 did not play a leadership or management role in the offense, and nearly half had little or no prior criminal record.

Even so, Cook contends that prosecutors would lose a major leverage tool with weakened mandatory minimums, making it harder for them to get cooperation from defendants who would help them dismantle drug trafficking organizations.

“It’s absolutely right that it [mandatory minimums] encourage people to cooperate with law enforcement officials and identify others involved in a conspiracy,” Cook said. “There are strong incentives for offenders to not help us identify other participants, and this is the only tool we’ve got. These are not easy people to deal with. They understand one thing, and that is how long they will be in prison.”

Fitzpatrick counters that prosecutors still could effectively do their jobs with less severe mandatory minimum sentences.

“There will always be the give and take of plea bargaining and trying to get people to cooperate,” Fitzpatrick said. “I don’t think this statute undermines that, not when high-level offenders will still get significant prison time.”

The Department of Justice is already encouraging prosecutors to charge offenders more liberally with crimes carrying mandatory minimum punishments.

In an August 2013 memo, then-Attorney General Eric Holder directed federal prosecutors not to punish low-level drug offenders with charges requiring mandatory minimums.

Last October, in testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee, Deputy Attorney General Sally Yates acknowledged the memo’s impact, noting that since Holder’s directive, the department has decreased its charging of mandatory minimum drug offenses by 20 percent.

“Although some feared that defendants would stop pleading guilty and stop cooperating, our experience has shown otherwise,” Yates said in her testimony to Congress. “In fact, defendants are pleading guilty at the same rates as they were before. Similarly, the rates of cooperation have remained the same or even ticked up slightly.”

Despite Yates’ assurances, Cook sees Holder’s directive as one piece of a weakening in sentencing rules and guidelines that he says has occurred over the last few years.

The Supreme Court in the 2005 case United States v. Booker ruled that federal sentencing guidelines are not mandatory, and that judges can use discretion to apply punishment that is “sufficient but not greater than necessary.”

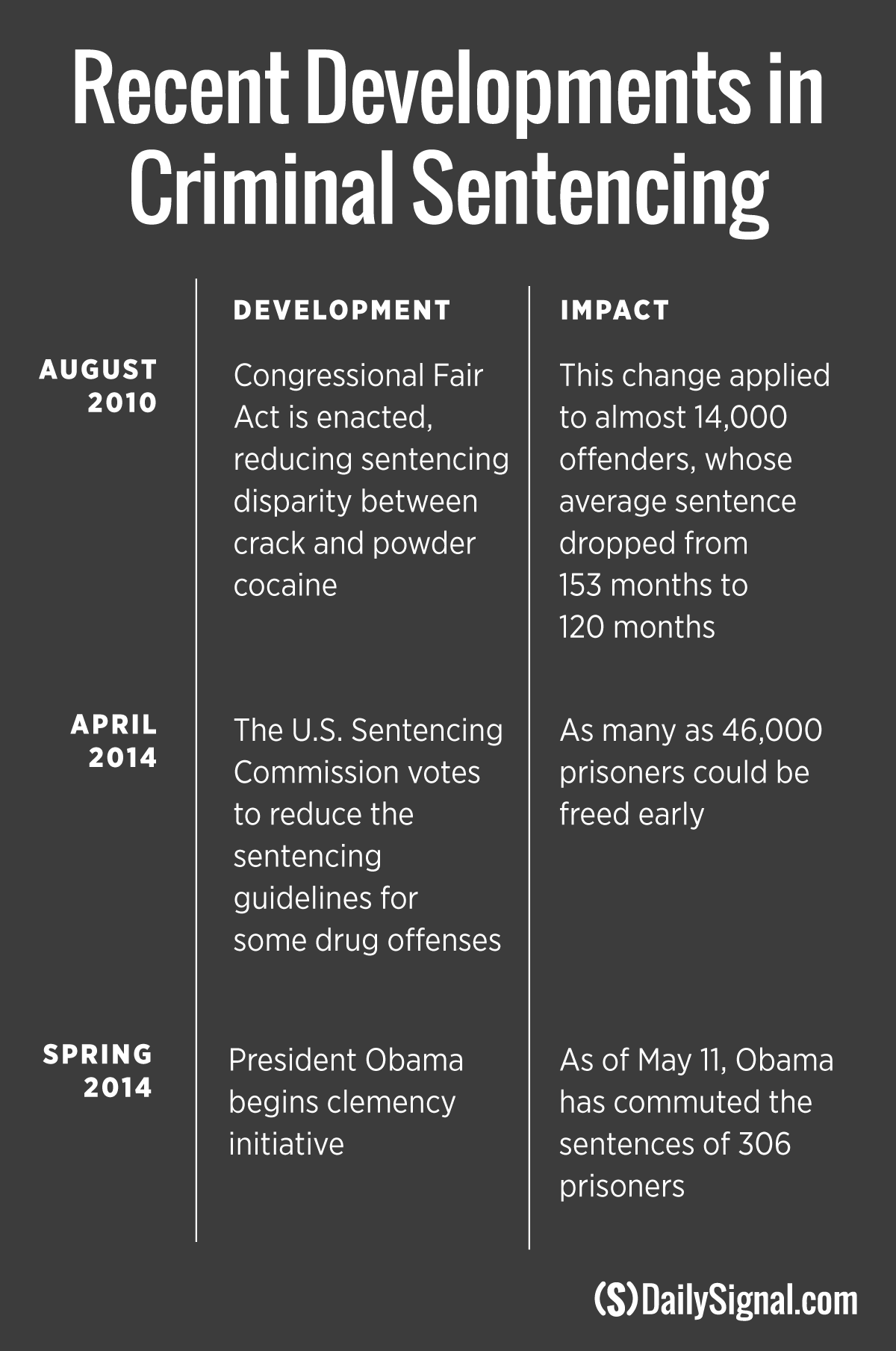

Meanwhile, in April 2014, the U.S. Sentencing Commission, an independent agency made up of seven bipartisan members who set the guidelines for federal crimes, voted to reduce the guidelines for some federal drug offenses.

The commission made the sentencing reduction retroactive, meaning federal prisoners already incarcerated could get out early.

Late last year, about 6,100 inmates convicted of drug crimes were freed, in the largest one-time release of federal prisoners. As many as 46,000 people total could have their sentences reduced. But even when applying the changed sentencing guidelines, a judge cannot impose punishment less than the mandatory minimum.

Other recent reforms include Congress’ 2010 passage of the Fair Sentencing Act, which changed the law to reduce the 100-to-1 sentencing disparity between offenses involving crack and powder cocaine.

The new Senate bill would make the Fair Sentencing Act retroactive, allowing approximately 5,800 crack cocaine offenders to petition courts to leave prison early.

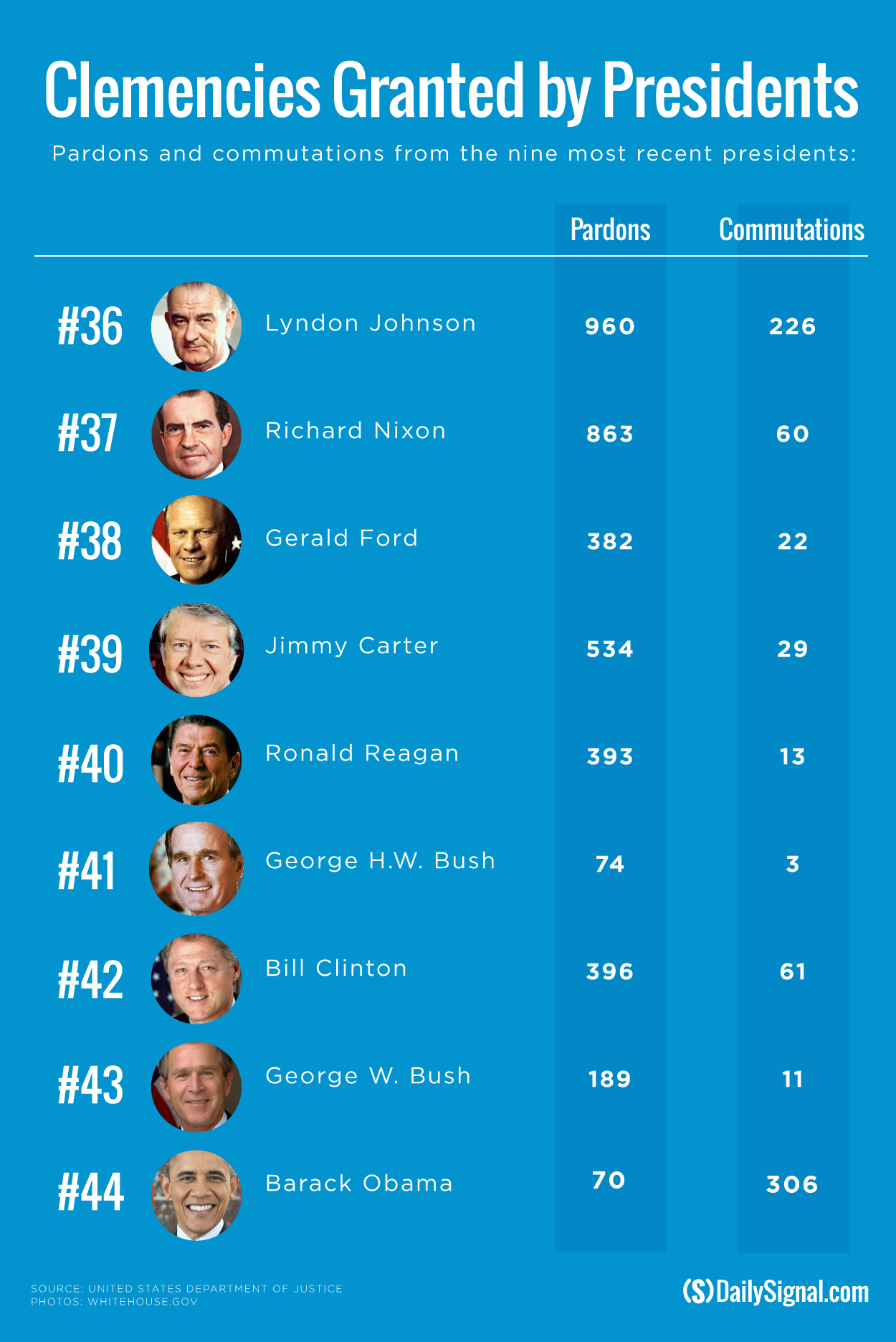

And finally, Obama has acted alone to shorten sentences for drug offenders, granting commutations to 306 inmates, 110 of whom were serving life sentences.

Cook, and prominent senators who oppose reducing mandatory minimums, insist that these developments in criminal sentencing, combined together, are significant.

These critics believe Congress should wait longer to see how the prior sentencing changes impact crime before acting again, especially as murder rates rose in many U.S. cities last year (although overall crime declined).

“We have gone far enough, we are moving too fast, and my best judgment, from many, many years in law enforcement, is that the bottom on crime rates has been reached, and the rise we are beginning to see is a long-term trend, not an aberration,” said Sessions, the Alabama senator, who spoke against the legislation at a press conference on May 11 with Cook and other law enforcement officials.

“The last thing we need to do is a major reduction in penalties,” Sessions added.

The federal prison population is, in fact, declining. In 1980, the federal prison population was about 24,000. By December 2013, there were about 216,000 inmates in federal prison, according to the Bureau of Justice Statistics. As of May 12, there are 195,914 federal prisoners.

Fitzpatrick and sentencing reform advocates, however, say the time for Congress to act is now, and that reductions to mandatory minimums would be more meaningful than the reforms before it.

Almost half of all federal drug offenders who went to prison last year received mandatory minimum sentences. Only Congress can reduce mandatory minimums.

“Look, I am not a softy,” Fitzpatrick said. “I am just as concerned about public safety as Steven [Cook] is. But we can’t lose sight of the big picture. If I lock up someone up for life, the public will be safe, maybe, but the family will also be destroyed and the money spent to incarcerate them could be spent on rehabilitation and job training.”