Central Americans Are Crossing the Border Illegally at 2014 ‘Crisis’ Levels

Josh Siegel /

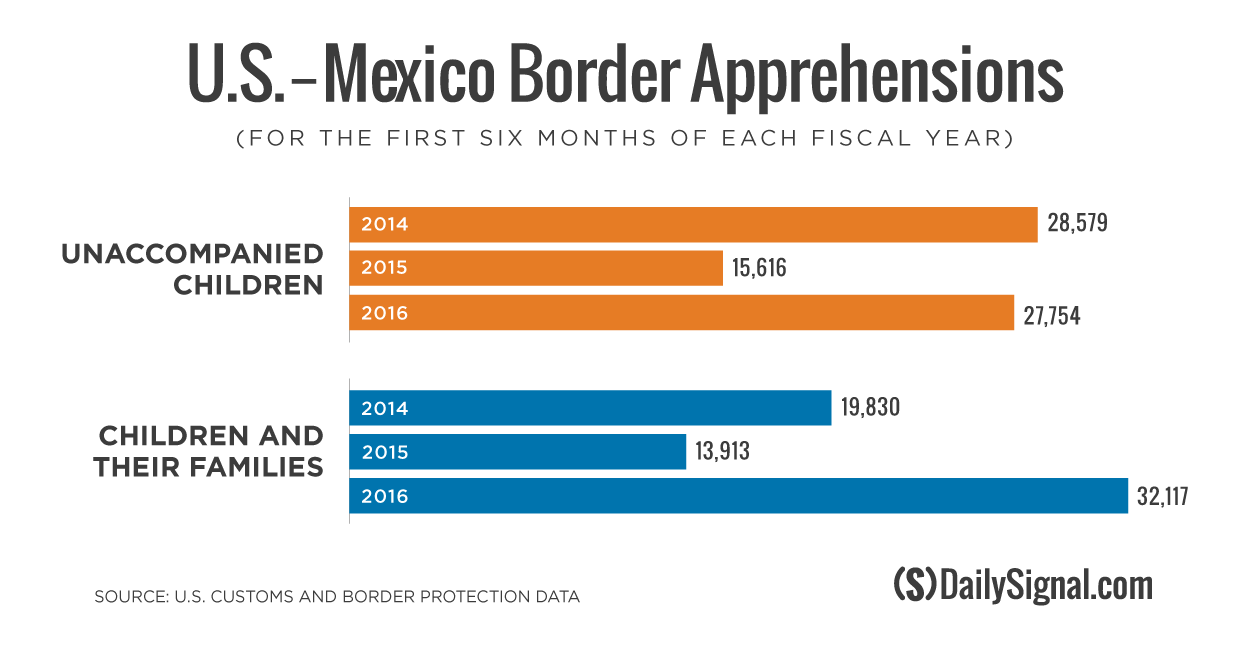

The number of children illegally crossing the U.S.-Mexico border alone during the first six months of this fiscal year is almost at the level of apprehensions that occurred in the same time period of 2014, a year when the Obama administration described the issue as a humanitarian crisis.

Children are coming with their families, meanwhile, at a rate almost double from two years ago.

The surge—both in 2014 and this year—is being driven by migrants fleeing violence, corruption, and poverty from the Central American countries of El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras.

The spikes are alarming immigration experts because crossings of the southwest border had declined after Mexico last year began better enforcing its borders—with help from the U.S.—and the Obama administration in 2014 pursued a public awareness campaign in Central America discouraging people from migrating.

According to data compiled by the U.S. Customs and Border Protection, apprehensions at the southern border this fiscal year of unaccompanied children, and families, is significantly up from 2015.

Experts tell The Daily Signal the sustained flow of illegal immigration from Central America shows the problem cannot be solved by enforcement measures alone.

“Our current policy of deterrence featuring interdictions and family detention won’t work in the long run—you need more of a protection scheme,” said Kevin Appleby, director of international migration policy at the Center for Migration Studies.

“You need a regional protection system that gives children and families an alternative to taking the dangerous journey to the United States.”

David Inserra, a homeland security expert at The Heritage Foundation, believes that the slow process of immigrants getting resolution to their cases at backlogged immigration courts, and the fact that few are being deported quickly, is giving incentive for migrants to travel here illegally.

“Our efforts with Central American governments on outreach may have had some success, but reality has caught up to public affairs,” Inserra said.

“People are seeing that if you come to the U.S. as a child or with your family, you are not going to be removed quickly.”

With the summer approaching, when peaks of illegal immigration usually occur, the Obama administration has started to prepare, with the Department of Health and Human Services requesting contingency funding to shelter apprehended children from Central America, who are given special protection under U.S. law and cannot be deported without a hearing.

In other efforts to deal with the challenge, the Obama administration is contesting a court ruling last year from a federal judge in California, who ordered that children and their parents temporarily held in detention centers (as they wait for a hearing on their status) should be released quickly, and that minors can’t be kept in facilities not licensed for child care.

In addition, earlier this year, Immigrations and Customs Enforcement began a series of raids targeting Central American families who have already been told by an immigration judge that they don’t qualify for asylum.

Yet the administration has also sought more enduring solutions. Late last year, Congress agreed to provide $750 million in spending to help Central American countries combat poverty, gang violence, trafficking, and government corruption, and to improve border security and social programs.

On Jan. 13, Secretary of State John Kerry announced an expansion of the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program to protect children and families from Central America.

The program was designed to screen migrants for refugee status before they make the dangerous journey to the U.S., which often involves them paying human smugglers.

Under the new program, any immigrant from El Salvador, Guatemala, or Honduras who is claiming persecution can apply to the United Nations for protection, but the laws determining eligibility to come to the U.S. as a refugee did not change.

Before the new program was created, only children with parents already living legally in the U.S. could apply in their home countries for refugee status here.

Appleby says these programs have been slow moving, because many children struggle to obtain legal representation and that Central American immigrants find it difficult to access processing centers.

The numbers would seem to back him up.

According to State Department data, there were 85 immigrants from El Salvador admitted to the U.S. as refugees from January through April, but only 12 migrants have been resettled from Honduras this year, and two from Guatemala.

While Inserra supports in-country processing and other efforts to discourage migrants from taking the dangerous journey to the U.S., he believes American policymakers can do more to enforce the law.

“The reality is there are pushes and pull factors, whenever you talk about how to stop illegal immigration,” Inserra said. “We can’t pursue a purely enforcement-based strategy. Working with the Central American governments to encourage rule of law, and to fight corruption and criminality, has to be a piece of it. Where we can help, we should, but we can’t control how well Honduras or El Salvador actually does those things. We can completely control how we enforce our own laws.”

Appleby argues the conditions driving Central Americans away from their home countries are so strong right now that U.S. policy only means so much.

“Regardless of what policies may or not be drawing them here, you have a push factor that is much stronger,” Appleby said. “The forces driving children and families are much stronger than the risks of the journey, at least in their mind, so they take their chances.”